The Reproductive Health Impact Study (RHIS) is a comprehensive research initiative that analyzed the effects of federal and state policy changes on publicly funded US family planning care from 2017 to 2024. The Guttmacher Institute worked with research and policy partners in four states—Arizona, Iowa, New Jersey and Wisconsin—to document the impact of these policies on family planning service delivery and the patients who rely on this care.

Arizona was selected as an RHIS focus state in 2018, in anticipation of state-specific shifts in federal Title X grantee funding. In selecting Arizona as a study state, researchers aimed to document how policy changes in family planning service delivery might affect a demographically diverse state with large numbers of immigrant, undocumented and Indigenous residents.

The information in this state profile reflects the landscape in Arizona during the RHIS study period. For the most current information about the sexual and reproductive health research and policy landscape in Arizona, visit our state information page.

Overall Findings

The RHIS findings demonstrate that restrictions on sexual and reproductive health care and rights undermine people’s reproductive autonomy through negative outcomes at the patient, provider and system levels. Additional and unexpected disruptions to the landscape during the study period, such as the COVID-19 pandemic and the US Supreme Court’s Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization decision overturning Roe v. Wade, exacerbated the harms of restrictive policies.

The main study findings include:

- All types of sexual and reproductive health care are inextricably linked, and policy restrictions on sexual and reproductive health care have broader implications.

- Programs and policies that support person-centered care and focus on sexual and reproductive health equity are key to ensuring reproductive autonomy for all patients.

- Cost is a significant barrier to patients’ ability to access care and achieve reproductive autonomy.

- Person-centered contraceptive care is essential because contraceptive preferences vary.

- Publicly funded family planning programs, including Title X, are critical to making contraceptive services affordable.

Arizona’s Sexual and Reproductive Health Landscape, 2017–2024

In 2020, Arizona was home to 1.5 million women of reproductive age (15–49), 33% of whom had incomes below 200% of the federal poverty level.1 In the same year, about 451,000 women in Arizona were considered likely to have a need for publicly supported contraceptive care.2

Arizona is a demographically diverse state, with 31% of residents identifying as Hispanic or Latino and 5% identifying as Indigenous (the third-largest Indigenous population in the United States). In 2016, 45% of Arizona women likely to have a need for publicly supported contraceptive care identified as Hispanic.3 Additionally, 15% of women in Arizona aged 15–49 were uninsured in 2019, compared with a national average of 12%.

Who Gets Publicly Funded Family Planning Services in Arizona?

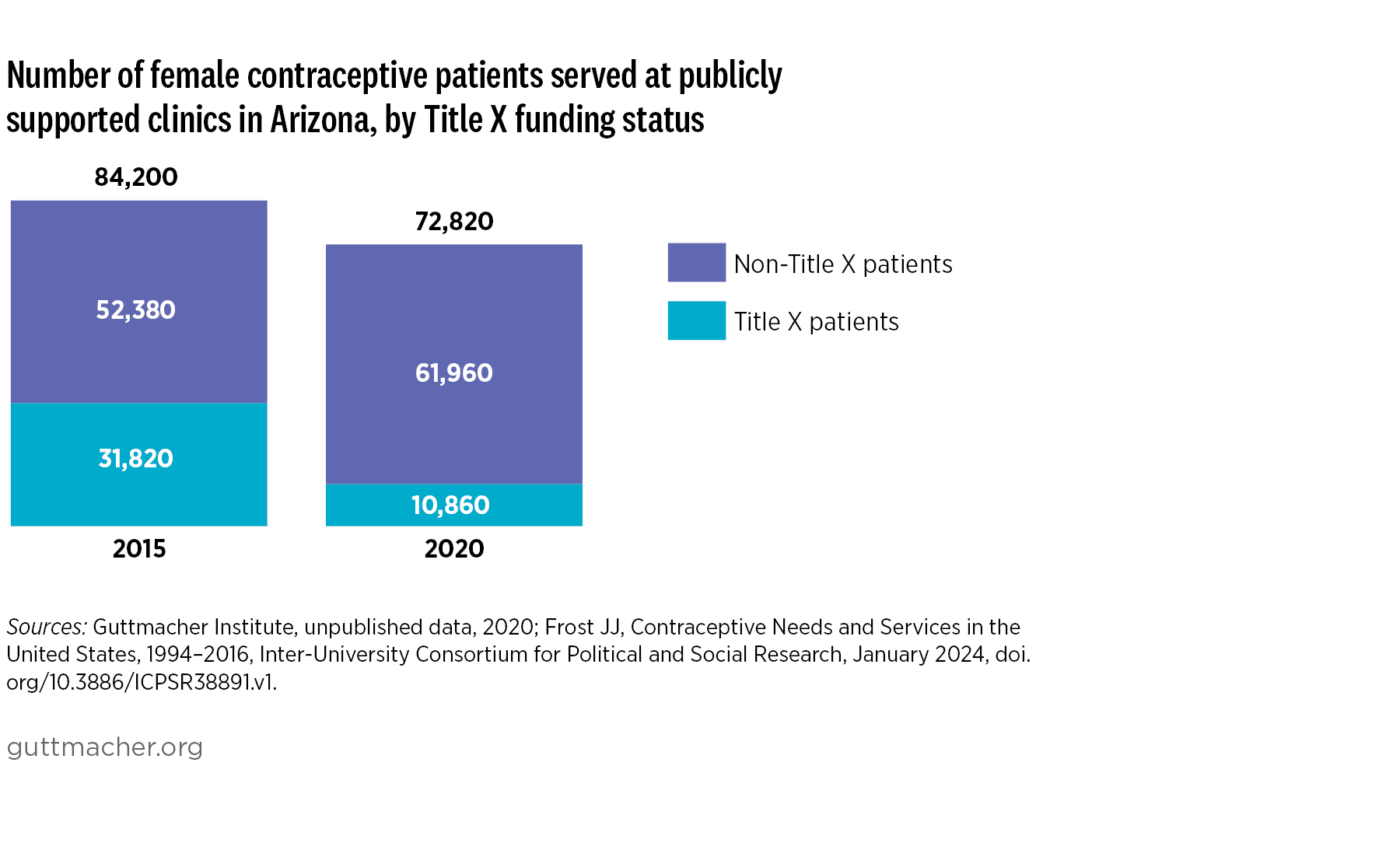

During the study period, the number of female contraceptive patients served at publicly funded clinics in Arizona decreased. A publicly funded clinic is a site that offers contraceptive services to the general public and uses public funds (federal, state or local funding through programs such as Title X, Medicaid or the federally qualified health center program) to provide free or reduced-fee services to at least some clients.

In 2020, about 73,000 female contraceptive patients were served at publicly funded family planning clinics in Arizona, a 14% decrease from 2015. Patients younger than 20 made up about 14,000 of this group, a 10% decrease from 2015.2

Only 16% of women in Arizona considered likely to have a need for publicly supported contraceptive care were served by publicly funded clinics in 2020, down from 18% in 2015.2

Where Do People Get Family Planning Services in Arizona?

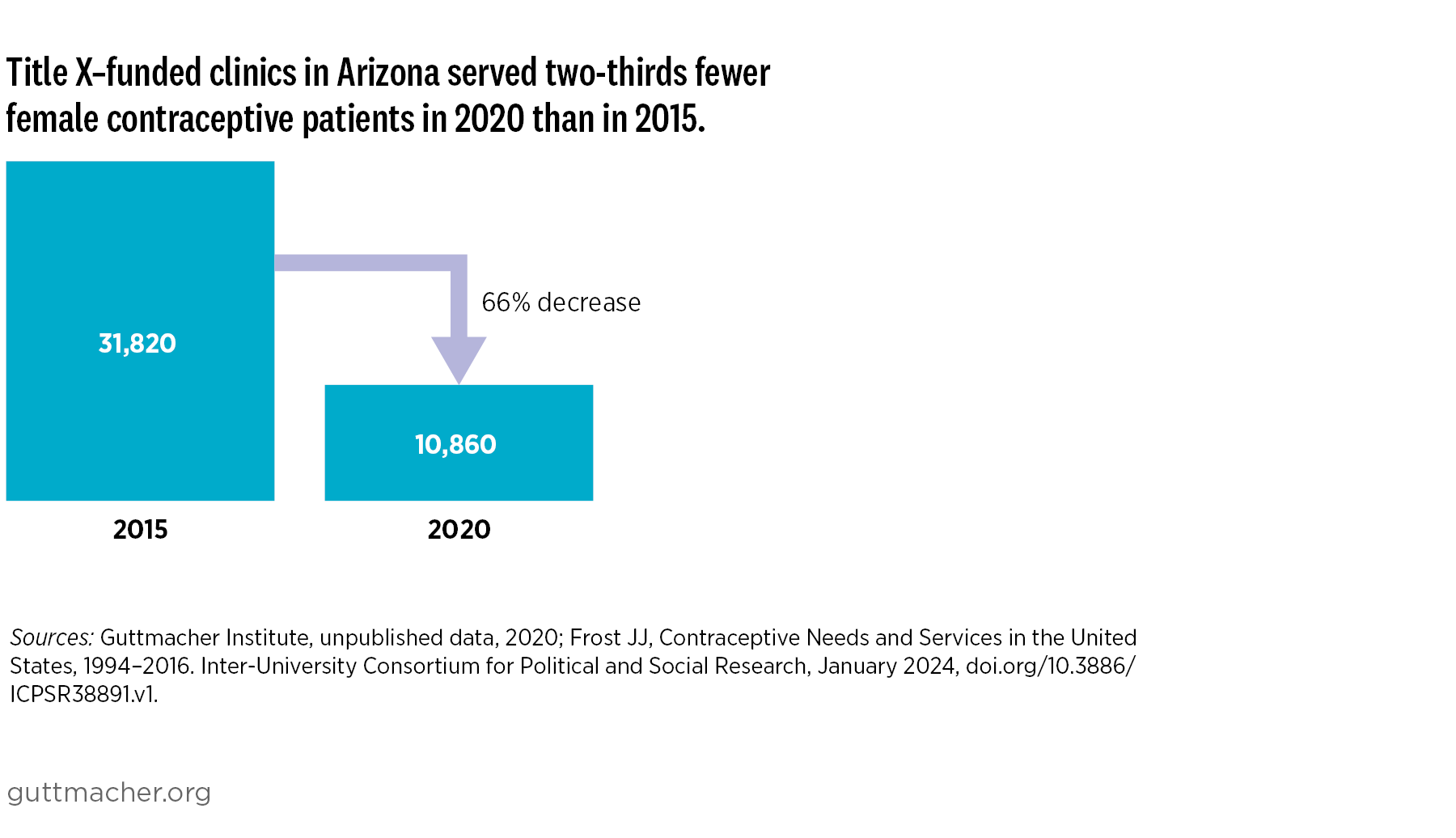

The total number of publicly funded family planning clinics in Arizona decreased by 8% from 2015 to 2020, from 232 to 214. Of that total, the number of clinics receiving Title X funding increased by 14%, from 36 in 2015 to 41 in 2020, but the new sites served far fewer contraceptive patients than those that had left the Title X network.2

In 2019–2020, women in Arizona aged 18–44 most preferred to get contraceptives in-person from a provider (70%), from a pharmacy (70%) and via telehealth (64%) for pick-up or home delivery. Across three states (Arizona, New Jersey and Wisconsin), 73% of women of reproductive age preferred more than one source for contraceptives.

What Family Planning Policies Changed in Arizona During the Study Period?

State and federal policy changes enacted during the RHIS study period disrupted the publicly supported reproductive health care system in Arizona. In 2017, the state legislature directed the Arizona Department of Health Services (DHS) to apply for Title X funding, which had historically been granted to Affirm AZ (formerly the Arizona Family Health Partnership). In 2018, 25% of the federal Title X grant ($900,000 total) was awarded to the Arizona DHS, which spent $100,000 of those funds but did not serve any contraceptive clients. In 2019, the Trump-Pence administration implemented a series of changes to the Title X program’s administrative regulations that included a ban on abortion referrals, required physical and financial separation of Title X–funded activities from any related to abortion, and mandated coercive counseling standards for pregnant patients.

As a result of this “domestic gag rule,” all Planned Parenthood affiliates left the Title X network later that year, although Planned Parenthood Arizona continued to offer family planning services via other funding streams. In 2021, the Biden-Harris administration’s Title X rule went into effect, revoking the 2019 rule and restoring the Title X national family planning program. Arizona and 11 other states filed a lawsuit to block the Biden-Harris rule, which resulted in some limitations to the rule in Ohio but not in other states. In 2023, following the election of a new attorney general, Arizona removed itself from the multistate lawsuit against the Biden-Harris Title X rule.

Patients’ Experiences of Reproductive Health Care in Arizona

The restrictive state and federal policy changes enacted from 2017 to 2024 negatively impacted Arizona residents’ ability to access reproductive health care.

Barriers to Accessing Care

Financial barriers resulting from these policy changes forced some Arizona residents of reproductive age to delay or forgo reproductive health care. Between 2019 and 2021, more than half of a sample of Arizona women seeking reproductive health care had postponed seeking care because of a lack of insurance or previous experience with burdensome or unexpected costs.

One Arizona woman seeking sexual and reproductive health services reported: “It impacted me when I went to the clinic that I used to go to before. They told me that the government had taken away all resources and could no longer provide support for free. And I didn’t know why that happened.”

Another shared: “They [the clinic] increased fees because they charged me less before, but since they ran out of funds, they now charge me more.”

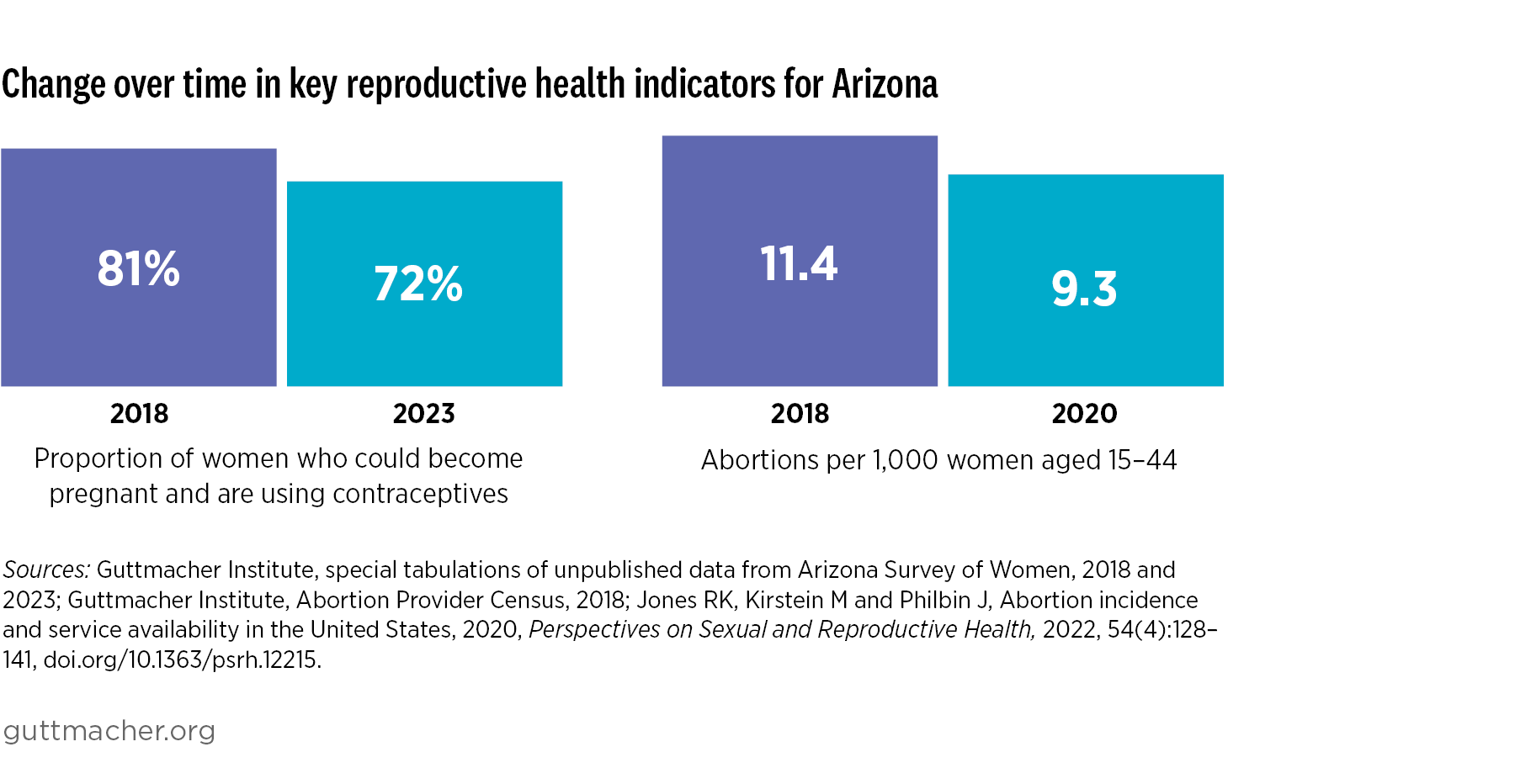

Restrictive state and federal policies undermine person-centered care, the patient-provider relationship and patient health outcomes. Person-centered care—health care responsive to an individual patient’s preferences and values—is a central tenet of reproductive autonomy. In 2019–2020, fewer than half (39%) of women aged 18–44 in Arizona reported receiving “excellent” person-centered contraceptive care in the previous year.4

Effects of COVID-19 and Dobbs on Care

The COVID-19 pandemic further exacerbated the harmful impact of restrictive sexual and reproductive health policies. Between May 2020 and May 2021, 57% of survey respondents at publicly supported health centers in Arizona reported that they were unable to access or delayed accessing sexual and reproductive health care, including contraceptive care, because of the pandemic. Respondents who had experienced financial instability during the pandemic were more likely than those who had not to experience pandemic-related delays in accessing sexual and reproductive health care.

Abortion-related policy changes during the study period also impacted people’s ability to access contraceptive care. In 2022–2023, 16% of reproductive-age women in Arizona reported having trouble or delays in accessing their preferred contraception, compared with 11% in 2021, before the Dobbs decision that overturned Roe.

Experiences of Marginalized Populations

A 2019–2022 study found that Arizona contraceptive patients at publicly funded clinics who had trouble getting their desired contraception over time reported lower levels of using their preferred contraceptive method and satisfaction with their current contraceptive method, compared with those who did not have trouble.3

This finding is particularly significant given Arizona’s large Hispanic and Latina population. Previous research has found that Hispanic and Latina patients have less access to sexual and reproductive health care and higher usage of publicly funded family planning clinics as their usual source of health care than non-Hispanic and Latina patients. These patients also face structural disparities, such as a lower concentration of neighborhood health services, less health insurance coverage, and worse access to educational and economic advancement, than non-Hispanic and Latina patients, as well as racial discrimination and stereotyping.

Arizona also has a large number of immigrant and Indigenous residents. National research findings indicate that noncitizen immigrants are disproportionately likely to be uninsured, to not receive regular health care (including sexual and reproductive health care) and to rely on publicly funded clinics for health care provision.

Similarly, people in Indigenous communities across the country are disproportionately uninsured and face systemic barriers to health care access that contribute to poor health outcomes. Although state-specific data are not available, national findings indicate that restrictive sexual and reproductive policies compound existing inequities. Therefore, the effects of the policies implemented during the RHIS study period are likely to have fallen particularly hard on marginalized groups in Arizona, including Hispanic/Latina, Indigenous and immigrant communities.

Reproductive Health Care Providers’ Experiences in Arizona

Restrictive state and federal policies disrupt providers’ ability to center and meet patients’ needs. They also increase existing inequities in sexual and reproductive health care, because these policies disproportionately impact marginalized groups.

Barriers to Providing Care

The state and federal policy changes enacted during the RHIS study period hindered publicly funded family planning providers in Arizona from offering patient-centered care. They negatively impacted clinic finances, providers’ ability to protect patient confidentiality, contraceptive counseling and service provision, and pregnancy options counseling.

Providers at clinics that opted to join or stay in the Title X national family planning program after the gag rule was enacted were required to prioritize fertility awareness–based methods and include parents in care decisions for minors (potentially compromising patient confidentiality). In addition, they were no longer able to provide comprehensive pregnancy options counseling.

One Arizona provider reported: “Honestly, that’s probably the biggest thing that’s changed. Not being able to bring up abortion as an option, not being able to give them direct, complete resources. We’re certainly able to talk about carrying a baby to term, adoption services, etc., but I think the biggest impact has been not being able to be forthright about [abortion] as an option.”

As a result of decreases or restrictions in funding, publicly funded family planning providers in all four RHIS study states—Arizona, Iowa, New Jersey and Wisconsin—had to rework payment options for patients. In some cases, they helped patients who would not otherwise be able to afford care access other government, clinic or donor funding sources.

Changes in Title X Funding

Between 2018 and 2021, 25% of Title X–funded clinics in Arizona left the Title X family planning program, likely because of the gag rule. In the same period, the share of publicly funded clinics providing comprehensive contraceptive counseling decreased.

COVID-19 and Reproductive Health Care Provision

The COVID-19 pandemic further complicated Arizona providers’ ability to provide person-centered sexual and reproductive health care during the study period. Family planning providers adapted their operations—including by implementing additional safety protocols, shifting service delivery and staffing to meet patient needs, and expanding telehealth services—to continue providing care during the pandemic.

Arizona’s Post-Roe Abortion Policy Landscape

Restrictive abortion laws can affect people’s ability to access contraceptive services, as well as family planning providers’ capacity to provide contraceptive and other sexual and reproductive health care. Whether or not a reproductive health care provider offers abortion services, the ripple effects of abortion policies impact all types of care.

The Dobbs decision led to confusion surrounding the status of abortion statutes in Arizona. In April 2024, the Arizona State Supreme Court ruled that an 1864 law that banned abortion from the moment of conception, except when necessary to save the life of the mother, could be enforced. In May 2024, Arizona lawmakers voted to repeal this law. Abortion remains available up to 15 weeks in Arizona. The most current information about abortion-related policies in Arizona is available on Guttmacher’s interactive map of US state abortion policies.

State Partners

The Guttmacher Institute partnered with Affirm, Planned Parenthood of Arizona and other Arizona-based research and policy partners for the RHIS. Additional information about reproductive health-related data and policies in Arizona can be found in the following resources:

NOTES

1. Throughout this profile, we use the terms female and women to refer to individuals who may have the ability to become pregnant. However, not everyone who has the capacity to become pregnant identifies as female or as a woman. A limitation of the data sources used in our analyses is that they do not provide further detail on the sex or gender identity of respondents.