One year since the global spread of COVID-19 began, the seismic disruptions that the pandemic has provoked are well documented: overburdened health systems, intensifying inequities, heightened political polarization and more. It is now clear that the pandemic has potentially set back global health efforts by decades, including when it comes to sexual and reproductive health and rights.1

But the global community has a clear roadmap for recouping these losses and driving progress toward the fulfillment of established commitments. Principal among these are the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) set by the United Nations (UN) General Assembly and adopted in 2015 by 193 countries, including the United States; they commit countries to providing universal access to sexual and reproductive health care services by 2030.2

To recover from the Trump-Pence administration’s systematic dismantling of sexual and reproductive health care and rights, as well as the immense challenges the COVID-19 pandemic has posed, it is vital that all stakeholders recommit to achieving these goals. This includes the incoming Biden-Harris administration and other donor governments, multilateral institutions, low- and middle-income country (LMIC) governments, and civil society organizations. However, true progress in this new global landscape requires not simply reverting to previous structures, but instead developing new, coordinated strategies to deliver equitable gains.

After abdicating its leadership role over the last four years and going further to hinder progress on global health initiatives, the United States must now step back into the global arena and reestablish itself as a collaborative, engaged partner. This means not only working with other actors to combat COVID-19, but also supporting efforts to restore and advance a progressive agenda on sexual and reproductive health and rights.

Immense Global Challenges

The COVID-19 pandemic has both created new global health challenges and laid bare the vulnerabilities in existing health care systems.

Gaps in Care Before the Pandemic

In 2019, there were 218 million women in LMICs who wanted to avoid pregnancy but were not using a modern form of contraception; annually, this led to 111 million unintended pregnancies and 35 million unsafe abortions.3 Tragically, 16 million women and 13 million newborns did not receive care for major complications in pregnancy and childbirth, and there were 299,000 pregnancy-related deaths and 2.5 million newborn deaths.

The challenges were even greater for key populations such as adolescents, who already faced immense gaps in access to sexual and reproductive health care. As of 2019, there were 14 million adolescent women aged 15–19 in LMICs with an unmet need for modern contraception. This contributed to 10 million unintended pregnancies among this age-group each year, as well as long-term negative effects including disruptions in education, professional opportunities and, fundamentally, reproductive autonomy.

Inequities such as these motivated a central pillar of the SDGs: to leave no one behind. While significant progress has been achieved on the SDGs overall in recent years, some disparities have persisted, including between rural and urban communities as well as by socioeconomic status, gender, age and other demographics.4,5

The Pandemic’s Impact

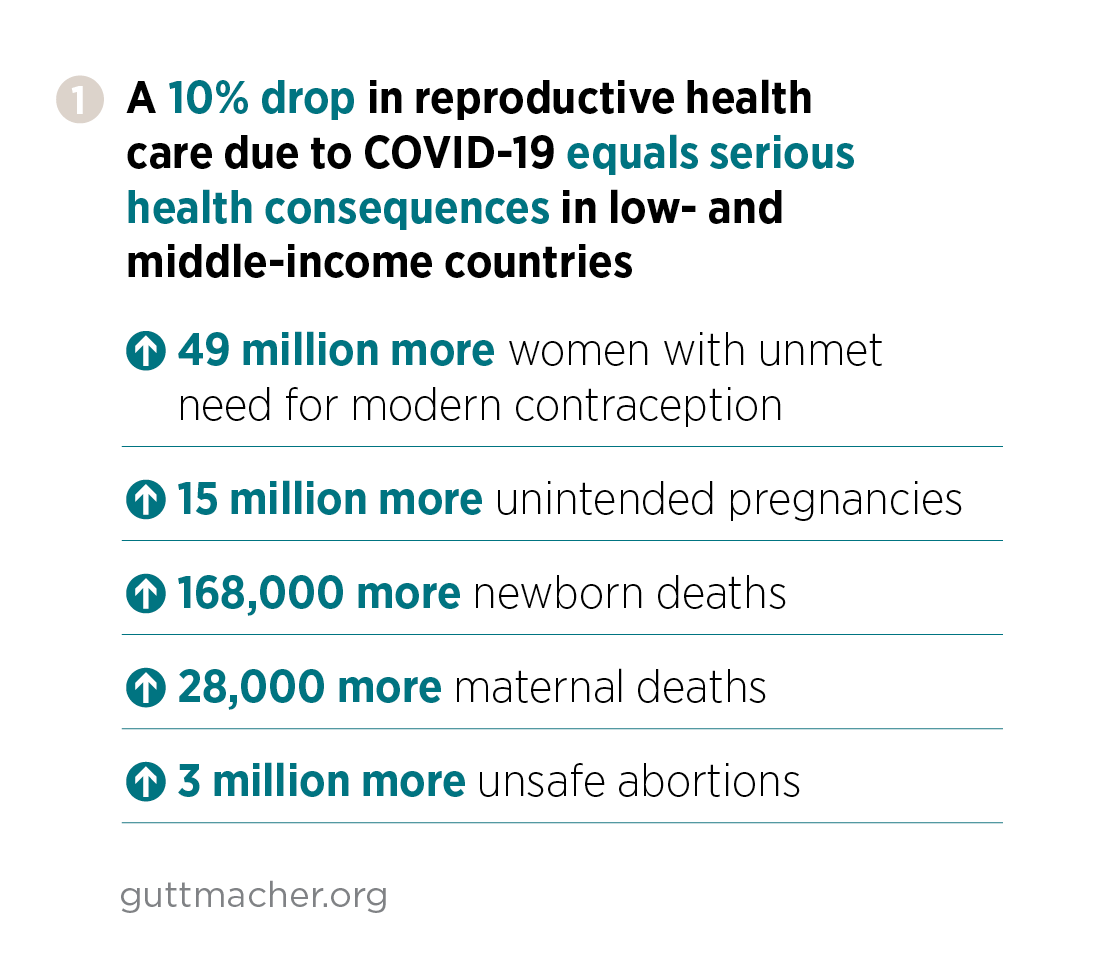

COVID-19 has taken this situation from bad to worse, as scarce resources and attention have been diverted away from sexual and reproductive health care to pandemic-related response efforts. Earlier this year, a Guttmacher team estimated how sexual and reproductive health outcomes could change in many countries following only a modest decline of 10% in access to care. The findings were staggering: A 10% decline in sexual and reproductive health care in LMICs would equal an additional 49 million women with an unmet need for modern contraception, leading to millions of unintended pregnancies and unsafe abortions and thousands of maternal and newborn deaths (see figure 1).6

While these estimated numbers are shocking, the reality could be far worse if sexual and reproductive health care declines by more than 10%. And the burden of reduced access to care is likely to fall hardest on people who already faced structural and systemic barriers to care before the pandemic, because these inequities are exacerbated under the weight of the global crisis.

Further, it is impossible to discern the full magnitude and diversity of these growing needs in light of chronic data-gathering challenges. Even before the pandemic, there was long-held frustration among advocates and policymakers about the lack of disaggregated data available on vulnerable populations globally, including people with disabilities,7 those living in humanitarian settings,8 LGBTQ people and others. The lack of data and halting progress toward developing appropriate cross-national and population-level data collection methods have been acutely felt over the past year, as the pandemic continues to hit these communities the hardest.

Even with robust data, meeting sexual and reproductive health needs has been stymied by unrealized innovations in health care technologies and service delivery methods, including telehealth; the importance of these innovations has become far more pronounced in the context of the pandemic. While digital tools and remote service delivery can overcome some barriers to high-quality care encountered in traditional health service settings—such as a perceived or real absence of privacy or confidentiality, stigma and provider biases—there remains a significant divide in online access, especially by gender.9

Abdication of U.S. Leadership

Even before the pandemic, sustained attempts by ideologically motivated governments—the United States chief among them—to reinterpret and subvert long-accepted global agreements on sexual and reproductive health and rights had left critical services like safe abortion increasingly vulnerable to attack.10 Rather than reacting to this crisis in a way that protects and advances people’s health and well-being, in the United States and globally, many policymakers have further curtailed essential care.11,12

During its tenure, the Trump-Pence administration repeatedly took aim at issues related to global sexual and reproductive health and rights, most noticeably through its repeated expansion of the "global gag rule."13 The administration’s expansion of this coercive and punitive policy was complemented by its attempts to eliminate federal funding for global family planning and reproductive health programs, proposed cuts to other global health programs, and hollowing out of technical capacity within the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) and the U.S. Department of State.14 On the multilateral stage, the Trump-Pence administration withdrew the United States from membership in the World Health Organization (WHO) and withheld funds from the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), severely undermining these long-standing global institutions.15,16 Together, these actions made the United States perhaps the single greatest obstacle to progress on sexual and reproductive health over the last four years.

Regaining and Accelerating Global Momentum

The COVID-19 pandemic has demonstrated the dire consequences of eschewing international cooperation and coordination, and these lessons should guide countries as they set out to rebuild their health systems and global partnerships. The UN’s Decade of Action and Delivery began in 2020, signaling the need to accelerate progress toward fulfilling the SDGs in their remaining 10 years.17 The SDGs provide a unifying roadmap for UN member states, including the United States, but must be coupled with new strategies that ensure everyone benefits from the ensuing gains in access to sexual and reproductive health care and rights.

To address the challenges unleashed by the COVID-19 pandemic and take substantial steps toward achieving full sexual and reproductive health and rights for all people, stakeholders should pursue the following actions.

Take a Comprehensive Approach

The call to "build back better" in the aftermath of the pandemic, embraced by the UN and the Biden-Harris administration, provides a critical opportunity to position sexual and reproductive health and rights as foundational to countries’ health systems. Multilateral agencies, the United States and other donor governments, and LMIC governments should prioritize sexual and reproductive health care in their rebuilding efforts, harnessing renewed momentum to achieve universal health coverage.18

The Guttmacher-Lancet Commission on Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights has provided a roadmap for countries to take gradual steps toward universal access to sexual and reproductive health and rights through mechanisms like universal health coverage.19 By integrating elements that are rarely recognized and addressed in global discussions, the Commission makes the case that investing comprehensively in sexual and reproductive health and rights is essential to sustainable development and human rights fulfillment at all levels, as well as providing cost savings over the longer term. The Commission’s model of progressive realization may be especially useful for policy and programmatic planning as countries face resource constraints in the context of the pandemic.

These efforts can also be bolstered by linking sexual and reproductive health and rights to new global initiatives, such as the 2021 Generation Equality Forum and burgeoning feminist foreign policy agendas.20,21 These endeavors seek to catalyze collective action for gender equality, which cannot be achieved without ensuring all individuals can make decisions governing their bodies and can access services that support that right. Recognizing the central role of sexual and reproductive rights in achieving gender equality can help drive progress for both agendas. This holds particular relevance in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. The secondary effects of the pandemic, such as reports of alarming increases in sexual and gender-based violence, have revealed the urgency of building more expansive coalitions to tackle these intersecting challenges.22

Prioritize Marginalized Populations

The pandemic has severely exacerbated inequities among and between populations, including along gender, racial, ethnic and socioeconomic lines. Multilateral agencies, donor governments and LMIC governments alike must tailor programmatic and policy interventions to respond to the needs of marginalized groups (e.g., people living in humanitarian settings, people with disabilities, those who are LGBTQ, and members of ethnic and religious minorities), many of whom were already being left behind in the implementation of global commitments like the SDGs and are now disproportionately impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic.23

For example, national governments should consult and use guidance from mechanisms like the COVID-19 Global Gender Response Tracker, which "monitors policy measures enacted by governments worldwide…and highlights responses that have integrated a gender lens."24 The tracker includes policies that directly address women’s economic security, safety and health, including those designed to increase access to sexual and reproductive health services. While developed in the context of the pandemic, the relevance of these policies will endure beyond it and should be considered for long-term adaptation and implementation.

Other pandemic-driven innovations have been developed specifically to meet the sexual and reproductive health needs of groups like adolescents, and should be embraced by countries moving forward. These include digital initiatives aimed at delivering comprehensive sexuality education to remote learners,25 WhatsApp channels for youth-friendly contraceptive counseling and virtual support groups for young people living with HIV, among others.

Innovate on Service Delivery

The pandemic has constrained access to sexual and reproductive health care, from facility closures to government-imposed restrictions on movement that have limited many people’s ability to travel and caused a surge in demand for telehealth and self-managed care options.26 While some governments have used the pandemic as a cover to further restrict access to essential sexual and reproductive health services, others have developed policies to facilitate home-based care, such as remote consultations for medication abortion.27

Policies and new service delivery models devised in direct response to COVID-19 disruptions that have temporarily expanded access to care should be integrated into health systems on a more permanent basis. In order to make long-term delivery of telehealth services feasible and equitable, some conditions must be met first, starting with access to high-speed internet access among patients and medical providers, new methods for ensuring health information privacy, and more favorable domestic policies on the use of such approaches.28,29

Governments should also identify ways to institutionalize other service delivery methods that have gained traction in the context of the pandemic, such as mobile clinic outreach for family planning services, patient call centers and task shifting to less specialized providers to expand service provision. Adopting some of the positive innovations that this global health crisis has stimulated will increase access to sexual and reproductive health care in the long term.

Pursue Financing Innovations

In order to mitigate the economic fallout from the pandemic, donor countries and development partners must develop equitable and sustainable funding strategies. To be effective, these approaches should prioritize country ownership in allocating investments for the provision of sexual and reproductive health care. For example, recent data suggest that targeted reforms, such as allowing health care providers more flexibility to manage incoming funds, can increase coverage for services like family planning and improve quality of care for patients.30

On a larger scale, universal health coverage will be a critical framework to adopt in repairing health care systems and providing services for those most in need in the aftermath of COVID-19. Achieving gains in health coverage will ultimately hinge on countries’ ability to sustainably finance their own health systems. This has increased calls for countries to mobilize additional domestic revenue in order to help finance their own development and lessen dependence on foreign aid. Donor countries and development partners such as the Global Financing Facility, a global partnership housed at the World Bank, can work with finance ministries to support policy initiatives aimed at strengthening the mobilization and effective use of domestic resources.31 Examples of such reforms include the development of progressive tax systems that apply higher tax rates to higher levels of income, improved tax policy and more efficient tax collection.32

Reestablishing U.S. Leadership

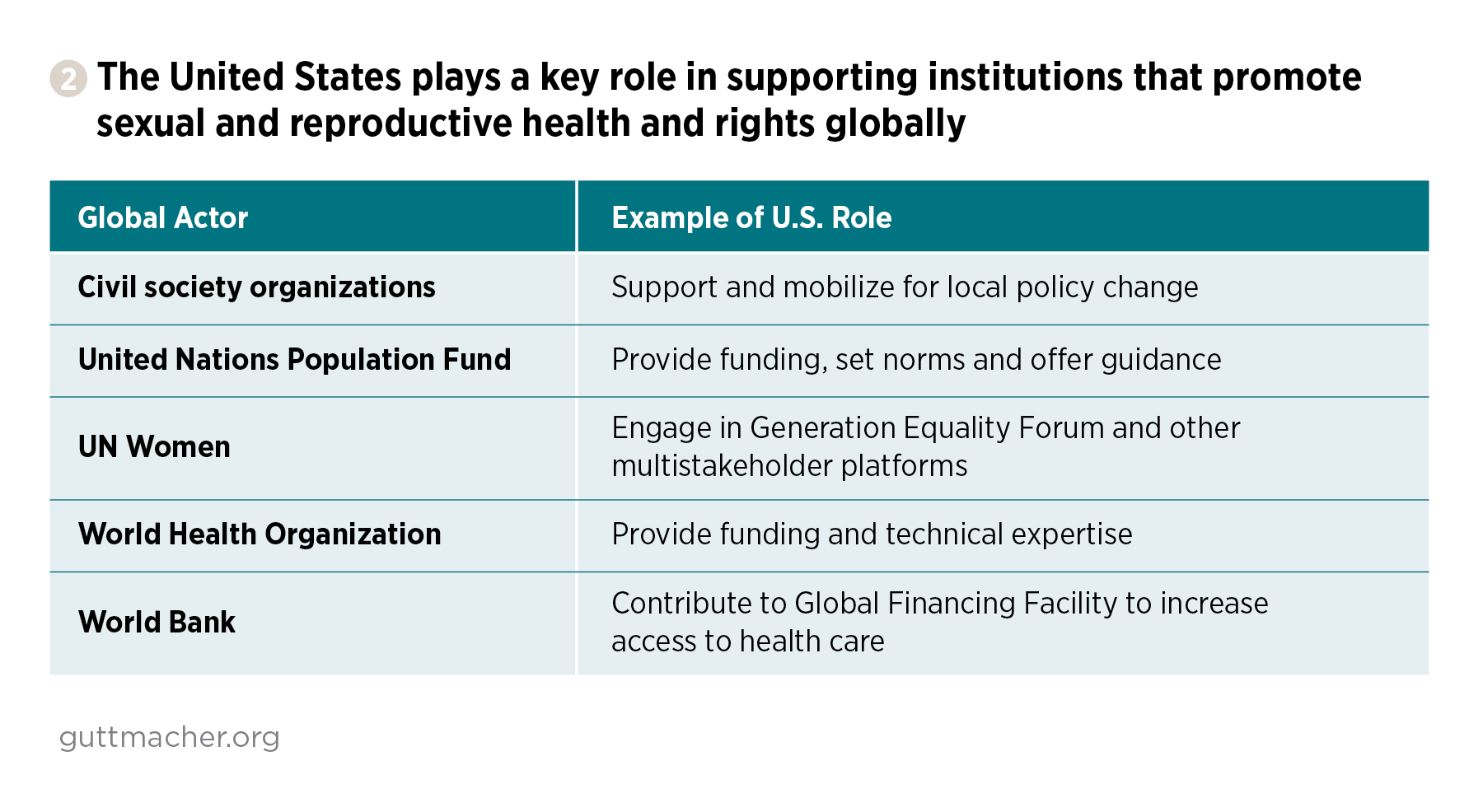

With the arrival of the Biden-Harris administration, the United States has the chance to articulate a new, ambitious vision for sexual and reproductive health and rights, in support of the broader global vision described above. This new vision should be well funded, programmatically flexible and focused on the people and communities with the greatest needs, while also aligning with the principles of a feminist foreign policy lens and broader development goals. While it may be tempting to revert back to the policies and programs of the Obama-Biden administration, the harms done by the Trump-Pence administration and COVID-19 demand a more robust, multifaceted and innovative response. It is time for the United States to reimagine its role and contributions to improving global sexual and reproductive health and rights in a changed world (see figure 2).

Reengage and Lead on the World Stage

During the four years of the Trump-Pence administration, the United States abdicated its position as the leader on global health, culminating in announcing a withdrawal from WHO membership in 2020.15 The administration used its anti–sexual and reproductive health agenda as a rallying point for the regressive regimes of the world; the recent nonbinding Geneva Consensus Declaration, which establishes a coalition of countries with an antiabortion stance, is perhaps the most extreme example of how the administration used an antiabortion ideology to score political points internationally.33

The Biden-Harris administration has begun to turn the page on this shameful period and to show support for global governance. In its first weeks in office, the new administration stopped the U.S. departure from the WHO, directed the State Department to take steps to resume funding to UNFPA and directed agencies to withdraw the United States from the Geneva Consensus Declaration.34,35 These steps will enable the United States to show the leadership it should have demonstrated on the global COVID-19 response from the start and help ensure that sexual and reproductive health is an integrated part of the worldwide response.

Given that the U.S. government has a megaphone globally, it should use its voice to call attention to urgent issues and support the multilateral gatherings where they are discussed. This should start with recommitting to fulfillment of the SDGs, but it cannot end there. For example, the United States should take a proactive role in the Generation Equality Forums and other events focused on women’s health and rights, as well as lead on these issues in annual UN negotiations.

As the Biden-Harris administration rebuilds a beleaguered State Department, it should encourage all of its diplomats to use the proper channels of communication to be clear that the United States supports a progressive, proactive approach to sexual and reproductive health and rights driven by science and evidence. Hopefully, the Biden-Harris administration will engage in diplomacy, both in public and private, with the small group of countries holding an anti–sexual and reproductive rights perspective and encourage them to reengage fully in the UN structure and process, rather than ideologically driven ad hoc groups, as was done with the Geneva Consensus Declaration.

Move Toward Paying the U.S. Fair Share

To be truly effective, the United States must back up its rhetoric with resources. This starts with appropriating the full U.S. fair share for global family planning programs, roughly $1.66 billion per year.36 Currently, the United States contributes just 36% of that, about $607 million per year, leaving a huge gap in global resources.

Recognizing that tripling funding for the program in a single year is not likely to happen, the advocacy community has laid out a five-year funding trajectory to get the United States to that target. If the Biden-Harris administration and Congress were to appropriate the recommended $1.03 billion for fiscal year 2021, the impact would be profound. Through this $1.03 billion, more than 46 million women and couples would be able to use modern contraception, almost double the current number reached by U.S. family planning funding. This dramatically scaled-up effort would avert roughly 21 million unintended pregnancies, seven million unsafe abortions and 33,000 maternal deaths annually.37

However, given the devastation wrought by COVID-19 and the likelihood of increased unmet need for contraception, Congress must also include funding for UNFPA and other global family planning and maternal health programs in emergency supplemental appropriations. Although some of the progress made over the last few decades has likely been lost, if the Biden-Harris administration and Congress act quickly, those losses may be only temporary.

Address Outdated and Coercive Policies

The Biden team reversed the harmful and dangerous global gag rule shortly after taking office,34 but that is only the first step toward addressing the host of legislation that restricts the United States from supporting the full range of sexual and reproductive health services globally.38 In order to move the United States from being a hindrance to progress on reproductive health to a true champion of it, the Biden-Harris administration should work with Congress on several items, including permanent repeal of the global gag rule and the Helms Amendment (which in effect bars U.S. funding for abortion overseas), and a revision of the Siljander Amendment (which bars U.S. funding for abortion rights advocacy).39

In addition to fixing policies that affect bilateral aid, the Biden-Harris administration must support multilateral efforts on sexual and reproductive health, starting by addressing current restrictions on funds for global entities. Early in its tenure, the new administration should reverse the Kemp-Kasten determination currently in place. The determination, made by the Trump-Pence administration for the last four years, has led to withholding of funding from UNFPA under the guise that it supports "coercive abortion or involuntary sterilization," despite bipartisan analysis that it does not.16 In addition to reversing this decision, the Biden-Harris administration should champion the Support UNFPA Funding Act, which would authorize annual contributions to UNFPA for the next five years, and work with Congress to eliminate unnecessary and onerous restrictions on U.S. funds for UNFPA. UNFPA is one of the most effective reproductive health organizations in the world and works in incredibly challenging environments; the United States must recognize and fully support its efforts.

Rebuild Technical and Programmatic Capacity

Over the last four years, the Trump-Pence administration has decimated staffing capacity within the federal government, but few agencies have been hit as hard as the State Department and USAID.40 To repair America’s standing in the world and accelerate progress on global sexual and reproductive health, the Biden-Harris administration must focus on rebuilding these offices, as well as other parts of the federal government engaged on public health, such as many agencies within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Rebuilding these agencies must go beyond the capacities they had before January 2017 to supporting them to adapt to a world shaped by COVID-19, advancements in technology and changing social dynamics.

At the State Department, this means strengthening the Office of Global Women’s Issues so it can fully engage in a feminist foreign policy framework and connect sexual and reproductive health to broader issues of development, peace and security. The State Department should also ensure that incoming leaders and staff have a strong commitment to sexual and reproductive health and rights, as well as an understanding of how to use diplomacy, both in bilateral and multilateral contexts, to advance supportive policies. In the Office of the U.S. Global AIDS Coordinator, new leadership should work to better integrate HIV/AIDS and family planning efforts, taking advantage of multipurpose technologies, streamlined procurement systems and integrated service delivery channels.

At the program level, a rebuilt and revitalized USAID should be encouraged to scale up investments in telehealth, new technologies and new service delivery methods to meet the needs of underserved populations. The agency should also work to improve its measurements of progress to ensure that marginalized groups are not left behind, as has occurred in the past. Given that it works across multiple technical areas, USAID should more fully integrate sexual and reproductive health programs into its education, nutrition, development, environment, and maternal and child health work.

And finally, because governments cannot do this work alone, the United States must increase its support to civil society organizations around the world. These partners can help advocate to their own national governments for policy change, including over-the-counter access to contraception, liberalization of abortion laws and the long-term adoption of COVID-related innovations, such as multimonth dispensing of pharmaceuticals.

Forward Together

The world has been fundamentally changed by the COVID-19 pandemic and the devastating policies of the Trump-Pence administration. The question now before the global community and the Biden-Harris administration is how to move forward on sexual and reproductive health and rights under these changed circumstances. The answer cannot simply be a reversion to how things were in the "before" times. Rather, the answer must be a new vision that builds on past progress, addresses inequities and disparities, and adopts new technologies and approaches. The needs are too urgent, the problems too complex and the scale too massive for a single actor to tackle them alone; it is time for a new era of global partnership, innovation and change, with U.S. leadership once more at the forefront.