This report summarizes 2015 state-level findings from a large-scale study of six Indian states titled Unintended Pregnancy and Abortion in India (UPAI). Focusing on Assam, Bihar, Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh and Tamil Nadu, the report estimates the incidence of abortions occurring in facility and nonfacility settings. It also provides representative, in-depth information on the characteristics of abortion-related services (induced abortion and postabortion care) provided by public- and private-sector facilities, in addition to estimates of levels of facility-based provision of care for women with abortion-related complications. Finally, it uses abortion incidence data to estimate levels of unintended pregnancy.

Abortion and Unintended Pregnancy in Six Indian States: Findings and Implications for Policies and Programs

- Context of Abortion in India

- Past research on abortion incidence

- The changing landscape of abortion provision

- Incidence of Induced Abortion

- Abortion Provision in Health Facilities

- Provision of Postabortion Care

- Incidence of Unintended Pregnancy

- Implications of Findings for Policies and Practice

- Expand facilities’ capacity to provide abortion

- Broaden and strengthen the provider base

- Improve the quality of abortion-related services

- Improve MMA services

- Improve access to and quality of postabortion care services

- Improve data collection

- Conclusion

- Data and Methodology Appendix

- REFERENCES

Author(s)

, ,Reproductive rights are under attack. Will you help us fight back with facts?

PREFACE

"No woman can call herself free until she can choose consciously whether she will or will not be a mother."—Margaret Sanger

According to a 2016 study published in The Lancet by the Guttmacher Institute and the World Health Organization, an estimated 56 million abortions took place globally each year between 2010 and 2014. These numbers make a strong case that abortion is a vital part of health care and should be easily available when needed.

It was a proud moment for India when its proactive parliamentarians legalized abortion with the historic Medical Termination of Pregnancy Act of 1971, creating a framework meant to protect women from the grave risks of unsafe abortion. Unfortunately, in spite of this legislative protection, unsafe abortion remains the third leading cause of maternal mortality in India, and close to eight women die from causes related to unsafe abortion each day.

This is why the provision of safe, effective and accessible abortion services is a priority in the Government of India’s current Reproductive, Maternal, Newborn, Child and Adolescent Health (RMNCH+A) programme. This and other governmental initiatives need reliable information for their planning and implementation, and yet comprehensive data on abortion incidence and service provision has been limited.

The Incidence of Abortion and Unintended Pregnancy in Six Indian States: Findings and Implications for Policy and Programs provides such data for six states from each region of the country: Assam, Bihar, Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh, Tamil Nadu and Uttar Pradesh. This major new body of evidence covers abortion provision at all levels—primary to tertiary—of public- and private-sector health facilities and also estimates the incidence of unintended pregnancy, the precursor to most abortions.

I would like to commend and congratulate the International Institute for Population Science, Mumbai; the Population Council, New Delhi; and the Guttmacher Institute, New York, for working closely with the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare to bring these valuable data to the public. Findings from the study will provide vital evidence to support the government’s current efforts—and, I hope, will inform many other such efforts—to make this legal reproductive health service safe and accessible and, thus, prevent morbidity and mortality due to unsafe abortion and improve the well-being of women and families across the country. And while the accessibility and availability of safe, legal abortion is a major public health necessity, providing a safe abortion is also about reproductive choice and entitlement, rights and justice. Hopefully this study will enable all those involved with the improvement of women’s health to take safe abortion in India to the next level.

Dr. Nozer Sheriar

Chair, Scientific Programme Committee, International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics

Former Secretary General, Federation of Obstetric and Gynaecological Societies of India

Member, South East Asia Region Technical Advisory Group, World Health Organization

Context of Abortion in India

Induced abortion has been legally permitted in India on broad grounds since 1971,1 yet representative information on access to abortion services and abortion incidence has remained scarce. The lack of comprehensive estimates of abortion incidence has in turn prevented the accurate estimation of the incidence of total pregnancy and of unintended pregnancy because abortion is a key component of these indicators. Reliable measures of abortion and unintended pregnancy are vital to obtaining a clear picture of how successfully women and couples are able to achieve their fertility goals, and gaps in such knowledge have limited the ability of government at the state and national levels to design policies and programs that ensure equitable access to safe and legal abortion, postabortion care and contraceptive services.

This report summarizes 2015 state-level findings from a large-scale study of six states, titled Unintended Pregnancy and Abortion in India (UPAI), that seeks to fill some of these evidence gaps. Focusing on Assam, Bihar, Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh and Tamil Nadu, the report:

- estimates the incidence of abortions occurring in facility and nonfacility settings;

- provides representative, in-depth information on the characteristics of abortion-related services (induced abortion and postabortion care) provided by public- and private-sector facilities;

- estimates levels of facility-based provision of care for women with abortion-related complications; and

- uses abortion incidence data to estimate levels of unintended pregnancy.

To provide new, reliable data on abortion incidence in India, we calculated and then summed estimates of each of the three components of abortion: surgical abortions and medical methods of abortion (MMA)* provided by health facilities, MMA provided in nonfacility settings (i.e., somewhere other than a public, private or NGO health facility), and other types of abortions provided in nonfacility settings. In addition to presenting estimates of the incidence of abortion, pregnancy and unintended pregnancy, this report also highlights findings on service provision that are relevant for informing policies and programs. The sources and methodologies used to calculate the estimates are detailed in the Data and Methodology Appendix, and in-depth analysis of data for each state can be found in individual state reports.2–7

Past research on abortion incidence

A few previous studies have provided state-level estimates of abortion incidence, but most have relied on incomplete sources of data. Statistics compiled by the government are known to greatly underestimate abortion incidence, both because reporting on facility-based services is incomplete and because many abortions occur outside of the facility setting. For example, over a 12-month period in 2014–2015, the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MoHFW) recorded only 4,877 induced abortions in Bihar—a state with more than 25 million women of reproductive age—while showing 62,466 in the much less populous state of Assam and 51,467 in Uttar Pradesh, the most populous state in India.8 In 2012, a study using two indirect estimation techniques (the Mishra-Dilip method and the Shah Committee’s method), placed abortion incidence in the six states far higher, ranging from 141,000–151,000 in Assam to 1,140,000–1,180,000 in Uttar Pradesh.9 However, these methods underestimate abortion because they are based on a small-scale survey and a survey of women. Meanwhile, the 2012–2013 Annual Health Survey estimated that the proportion of pregnancies ending in abortion was about 7% in Assam, 5% in Bihar, 3% in Madhya Pradesh and 7% in Uttar Pradesh,10–13 while a 2016 study placed this proportion for South and Central Asia at 25% for the period 2010–2014.14

Some community-based surveys (such as the National Family Health Survey, or NFHS) collect data on abortion directly from women. However, such studies cannot reliably collect data on incidence because, in response to the stigma associated with terminating a pregnancy, women typically underreport their abortions in face-to-face interviews, a problem that may be exacerbated if women believe abortion to be illegal.15–20

The most recent and most commonly cited national estimates of abortion in India placed incidence at 6.4 million abortions in 2002, corresponding to a rate of 26 abortions per 1,000 women of reproductive age.21–23 To arrive at this estimate, researchers applied the average number of abortions per provider (based on a survey of a small sample of 95 public and 285 private providers) to an estimated total number of abortion providers in the country, which in turn was based on the ratio of population to facility in the limited sample areas. State-specific components of the same study estimated annual induced abortion rates of 45 and 70 in Maharashtra and Tamil Nadu, respectively, which suggests that the study’s national abortion rate of 26 may have been highly underestimated.24,25 Notably, this study was conducted in 2002, when access to and use of MMA was much lower than it is today.

The estimation methodology used in the UPAI study improves on those of previous studies because it does not rely on incomplete official statistics, community-based surveys of women or small-scale facility surveys. Instead, it directly measures abortion using a representative large-scale sample survey of public and private health facilities that provide abortions, comprehensive data on sales of medication abortion drugs and indirect estimation techniques to account for other abortions occurring outside of facilities.

The changing landscape of abortion provision

Passage of the Medical Termination of Pregnancy (MTP) Act in 1971 legalized abortion up to 20 weeks’ gestation when it is necessary to save a woman’s life or protect her physical or mental health, and in cases of economic or social necessity, rape, contraceptive failure among married couples and fetal anomaly; it also legalized terminations beyond 20 weeks in cases of life endangerment.1,26 The MTP Act specified that abortion services must be carried out by obstetrician-gynecologists or by doctors with a bachelor of medicine, bachelor of surgery (MBBS) degree who are trained and certified to provide pregnancy termination, and that provision must occur in approved public or private facilities. Access to legal abortion was expanded by policy changes in 2002 and 2003 that approved the use of MMA for terminating pregnancies up to seven weeks’ gestation and permitted certified abortion providers with referral linkages to approved facilities to prescribe MMA drugs, even while working at unapproved facilities and doctors' offices.†28,29

With the approval of MMA for early legal abortions and large increases in the method’s availability in both the formal and informal sectors, access to abortion has steadily improved, likely becoming safer as a result.30,31 However, a number of hurdles continue to prevent full access to legal abortion services and lead some women to resort to the use of untrained informal-sector providers, including chemists and other vendors.32,33 Barriers to access include an insufficient number of facilities offering abortion care, lack of certified staff, shortages of equipment and supplies, failures to ensure privacy and confidential care, lack of knowledge among women that abortion is legal, and stigma surrounding seeking abortion-related care.18,19,32–36 Challenges also remain in addressing sex-selective abortion while protecting access to legal abortion. The Government of India’s strict measures to enforce the Pre-Conception and Pre-Natal Diagnostics Techniques (PCPNDT) Act of 2003, which prohibits the misuse of prenatal diagnostic tests for the purpose of sex determination,37,38 as well as intense public focus on this issue in recent years, has led to difficulties in both obtaining and providing safe abortion and postabortion care. For instance, a growing number of qualified providers are reluctant to offer pregnancy termination services because of both real and perceived strictures imposed by authorities attempting to restrict sex-selective abortions.39–41

Incidence of Induced Abortion

Abortion incidence is an important indicator of women’s need for safe termination services, and it sheds light on women’s and couples’ contraceptive behavior and their experience of unintended pregnancy. The UPAI study provides a comprehensive estimate of abortion incidence that reflects the full range of methods and providers that women use. In addition to estimating public- and private-sector abortion provision in health facilities, it estimates abortions occurring in the informal sector, including MMA provided by chemists and other informal vendors, terminations by untrained providers and abortions that women induce on their own. Our estimation methodology relies on health sector information whenever possible to avoid the high level of underreporting (often linked to concerns about confidentiality and stigma) that generally occurs in household surveys that directly ask women about their abortions.17,32,33

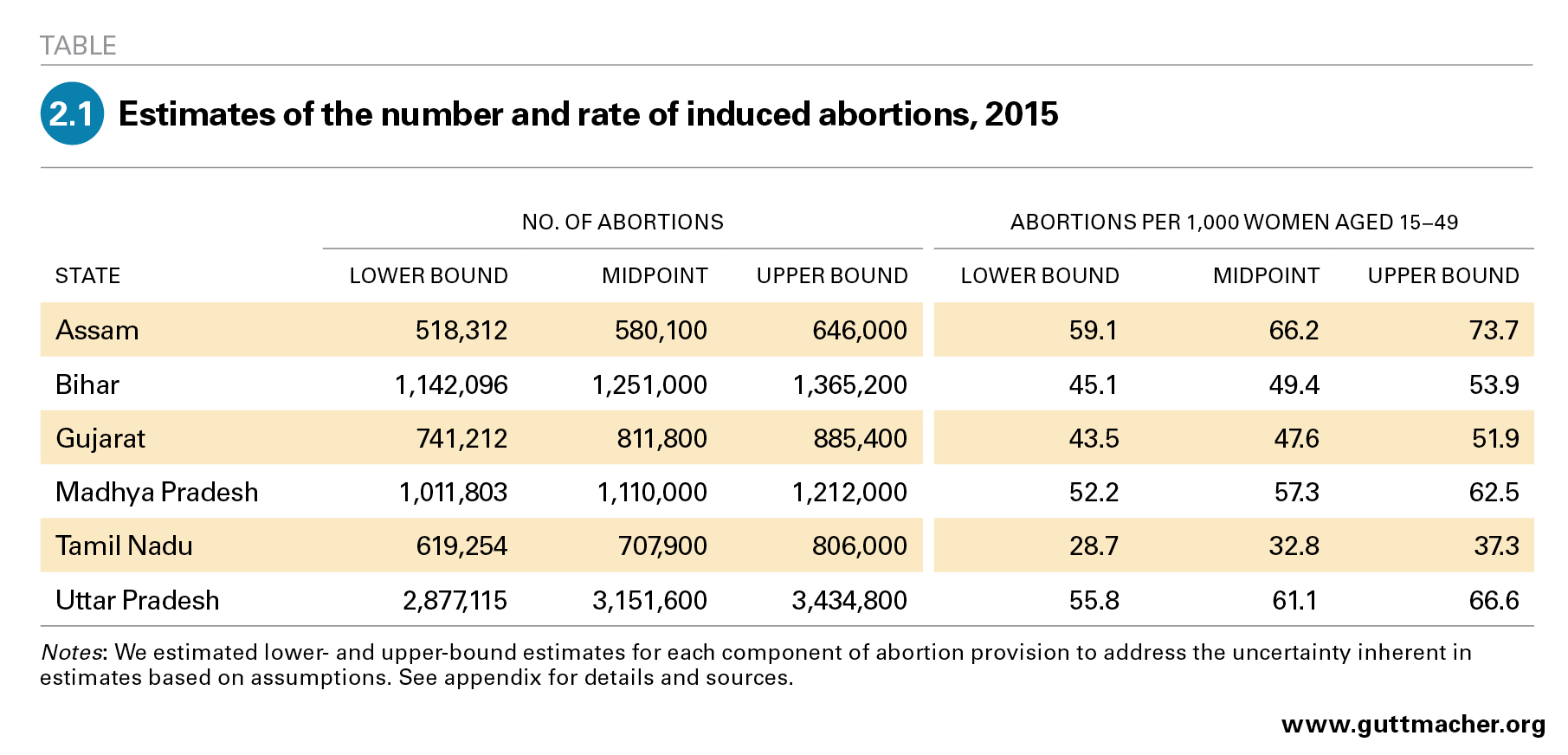

Using data for 2015, we estimate the annual incidence of abortion in the six states included in this study to range from 580,000 in Assam to 3,152,000 in Uttar Pradesh (Table 2.1). While absolute numbers reflect population size, among other factors, the abortion rate—abortions per 1,000 women aged 15–49—allows comparison of abortion incidence across states, removing the effect of population size. Although we focus on midpoint estimates of the abortion rate, we also present lower- and upper-bound estimates for each state—a range that reflects the uncertainty inherent in the estimation techniques. The midpoint abortion rate is lowest in Tamil Nadu (32.8) and highest in Assam (66.2), and the other four states have rates within this range: Gujarat (47.6), Bihar (49.4), Madhya Pradesh (57.3) and Uttar Pradesh (61.1).

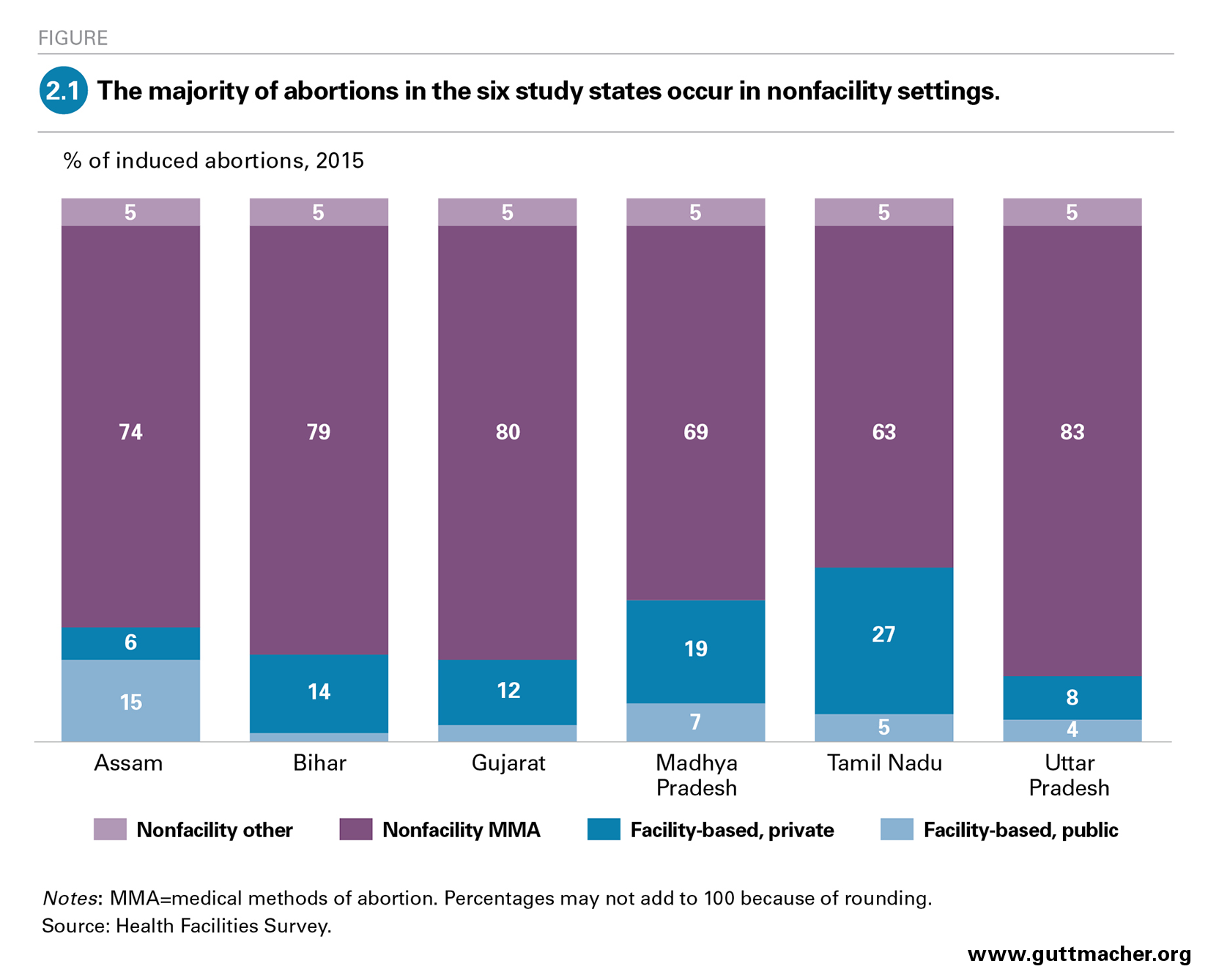

Only a minority of the abortions occurring annually in each state are provided in health facilities; these proportions range from about 11% in Uttar Pradesh to 32% in Tamil Nadu (Figure 2.1). These proportions likely represent slight underestimates of facility-based provision because some abortions are legally provided by trained doctors in private offices or consultation rooms that were not covered by the Health Facilities Survey (HFS). Among abortions that occur in health facilities, the majority are provided in the private sector‡ (68–92% in five states). The exception is Assam, where about three-quarters of facility-based abortions are provided in public facilities.

The majority of abortions in the six states (from 63% in Tamil Nadu to 83% in Uttar Pradesh) use MMA and take place in settings other than health facilities. In Bihar, Gujarat and Uttar Pradesh, nonfacility MMA accounts for four out of five abortions. MMA is safe and effective when administered properly; however, when it is provided outside of health facilities—and particularly when it comes from informal-sector providers—the quality of instructions and support to correctly use the medications is often low. An unknown (but likely small) proportion of women who terminate using MMA outside of facilities obtain good-quality MMA care at private consultation offices that includes accurate information and follow-up care from a trained provider. However, the limited evidence that exists suggests that the majority of users of MMA purchase the medication from chemists or other informal vendors and receive limited or inaccurate information and little or no counseling. One study in Madhya Pradesh found that about two-thirds of MMA-providing chemists and other informal vendors (who, the study notes, are the most common providers of nonfacility MMA) did not ask clients the timing of their last menstrual period, about four-fifths provided no advice or incorrect advice on the gestational limit for MMA, and roughly two-thirds did not provide correct information on administering the two-pill regimen.30 The authors concluded, "While pharmacists offer women an evidence-based procedure, the advice they offer does not conform to minimal medical standards so the abortion is, strictly speaking, unsafe. Yet most observers will agree that insofar as medical abortion has displaced clandestine or riskier methods such as traditional means of home abortion, fewer women will suffer severe complications or death."

A small share of abortions in each state (5%) occur in nonfacility settings and use methods other than MMA. These include the least safe terminations, undertaken by quacks and other untrained providers and by pregnant women themselves, though a small number of surgical abortions performed by trained professionals outside of the facilities covered by the HFS may also fall into this category. According to HFS data on postabortion care in the six surveyed states (discussed in greater detail in Chapter 4), a small proportion of postabortion care patients (who are a fraction of all women having abortions) are treated for uterine perforation, other injuries, sepsis and shock; these serious complications typically indicate the use of an unsafe method.

Abortion Provision in Health Facilities

Facility-based abortion care is part of the essential package of sexual and reproductive health services that health systems are expected to provide. Thus, it is important to examine the extent to which health facilities are offering these services, how provision differs by sector and facility type, and what barriers may limit the availability of these services. Perspectives on the accessibility of abortion services from women seeking such services are equally important, and this evidence gap should be addressed by future research. This chapter presents information about the provision of abortion from the Health Facilities Survey (HFS), which entailed interviews with key facility personnel at public- and private-sector facilities for each of the six study states. This new data provides an important evidence base for initiating and supporting policies and programs that address abortion access in each of the states. In addition, because these states are diverse and are home to approximately 45% of reproductive-age women in India, the findings may also provide policy-relevant insights at the national level.

In five of the six study states, the majority of facilities that provide induced abortion are in the private sector (data not shown). In these states, more than three-quarters of facilities that provide abortion are private and just 12–23% are public. Assam is the only state included in the study where the majority of abortion-providing facilities are public (55%).

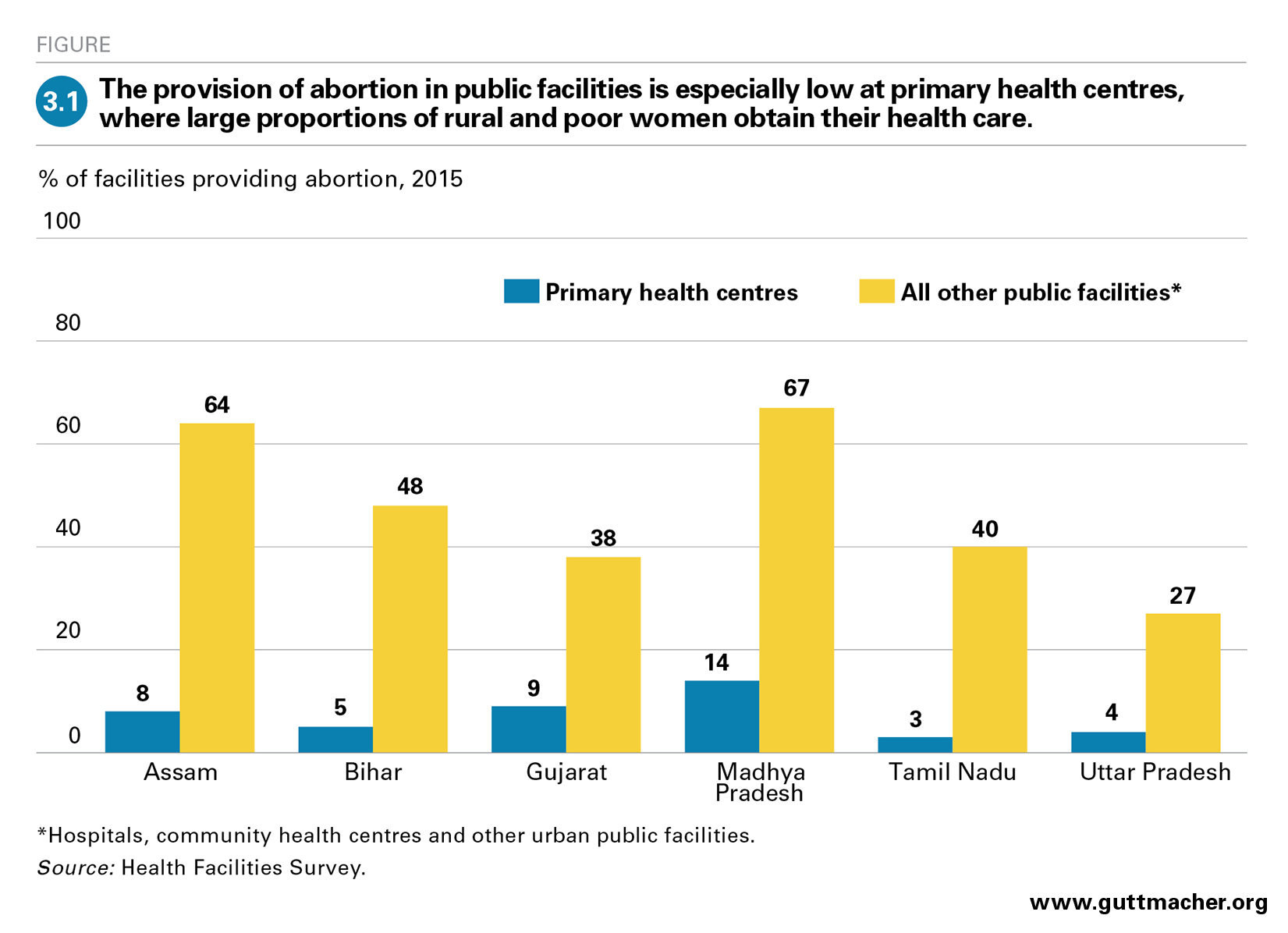

According to the guidelines issued by the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MoHFW), all public-sector facilities at the primary health centre (PHC) level and higher are allowed to provide induced abortion, as long as they have a certified provider on staff.42 Public facilities are well positioned to be the principal provider of abortions to many groups, including poor women, to whom they offer free services, and women in rural areas, where the public sector’s reach is much greater than that of the private sector. In practice, however, many public facilities do not offer abortion. PHCs typically have limited capacity to offer the service, and across the six study states, only a small proportion do so (3–14%; Figure 3.1). Community health centres (CHCs) and public hospitals should have the trained staff and equipment needed to provide abortion, but in four of the six study states, a minority of public facilities above the PHC level provide abortion (27–48%). Only in Assam and Madhya Pradesh do the majority of larger public facilities offer this service (64% and 67%, respectively). Similar data on the proportion of all private facilities that provide abortion are not available because the HFS survey was administered mainly to those offering the service.

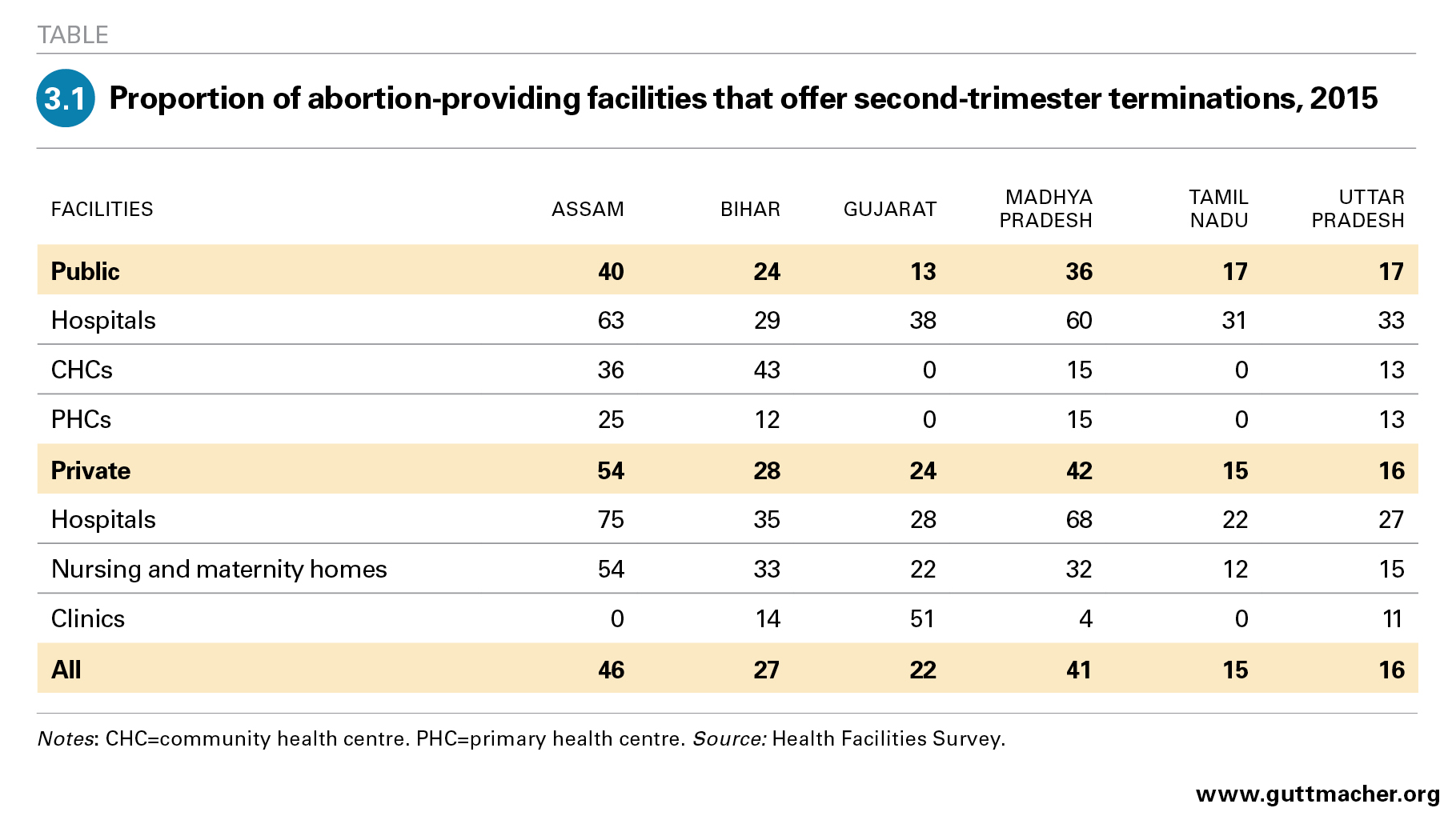

In both the public and private sectors, many facilities that offer abortion will not provide it beyond certain gestational ages that are well below the 20-week legal limit. Lower-level facilities may understandably need to refer later abortions to better-equipped facilities that are able to give more advanced care, but many higher-level facilities also do not offer second-trimester abortion. Among facilities that offer abortion in the six surveyed states, 29–63% of public hospitals and 22–75% of private hospitals provide pregnancy termination into the second trimester (Table 3.1). Even among these facilities, very few offer services up to the legal limit. Early limits can prevent some women from obtaining needed services or push them to seek abortion in the informal sector.

Among facilities that provide induced abortion, the majority (63–85% in the six states; data not shown) offer both MMA and surgical terminations. However, facilities offering abortion often use methods that are not in line with best practices for abortion care. World Health Organization guidelines recommend the use of MMA or vacuum aspiration for most abortions; dilatation and evacuation (D&E) is recommended in situations in which the other methods are contraindicated (typically in the second trimester); and dilatation and curettage (D&C) is no longer recommended as an abortion method at any gestation.43 However, in the six states surveyed, 25–37% of all abortions are performed using either of the two more invasive surgical methods—D&E or D&C—although only 4–13% of all abortions in these facilities are beyond 12 weeks’ gestation. We have grouped these two methods together because providers may use D&C as a generic term applying to both; therefore, proportions for each procedure may not be reliable.44

In all six states, the majority of facilities that offer abortion report having turned away at least one woman seeking to terminate a pregnancy in the year preceding the survey (54–87%; data not shown). While these facilities commonly report having turned away women for reasons related to lack of capacity, a substantial proportion do so for reasons that may reflect judgmental attitudes or a lack of understanding of the law. For example, 22–53% report having turned some women away because they are unmarried or have had no children, or because the provider considers them too young; smaller but still notable proportions (8–21%) turn away some women for not having the consent of their husband or another family member. These reasons generally are not legal grounds for denying an abortion in India.

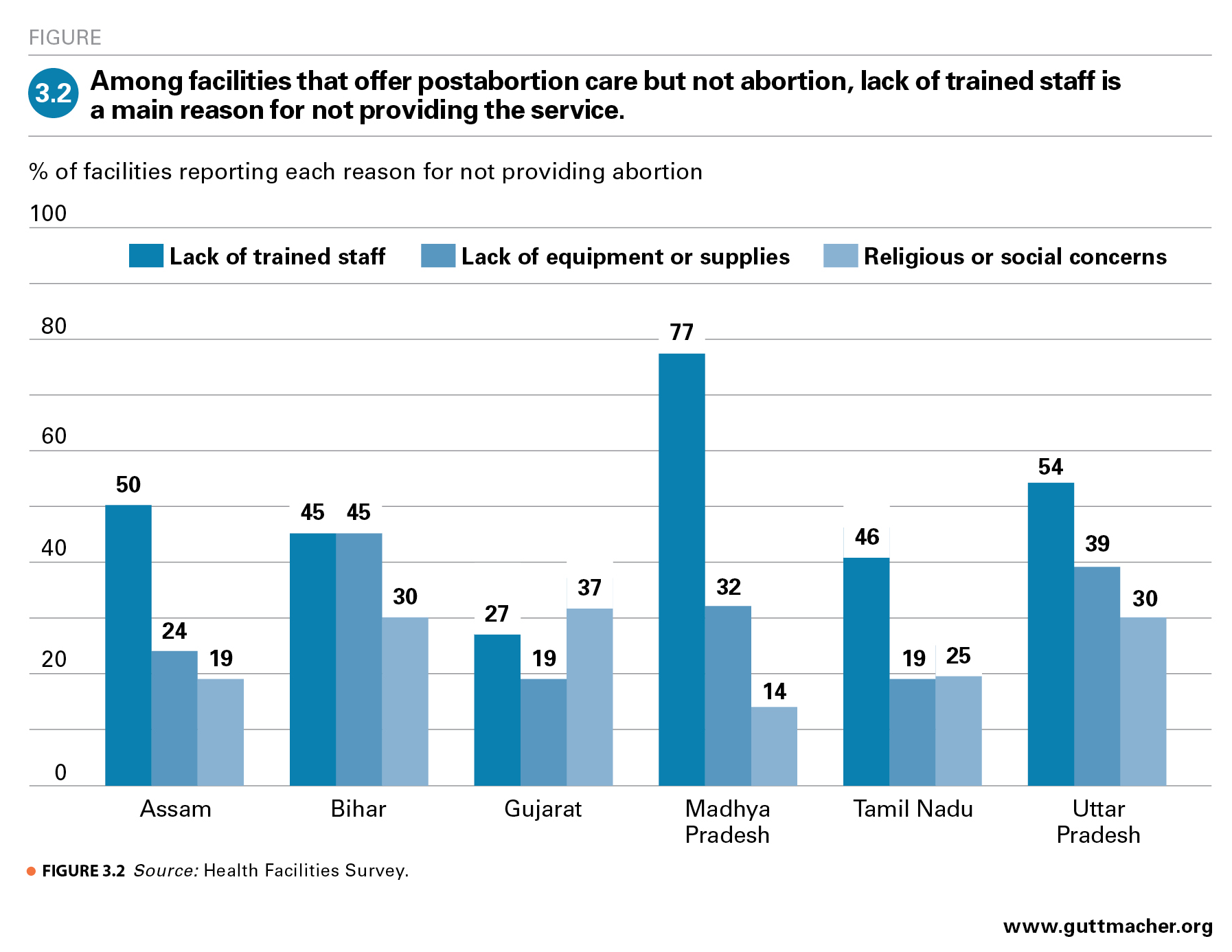

Respondents surveyed in the HFS identified a range of issues that contribute to limiting provision of abortion-related services. Among public and private facilities that offer postabortion care but not abortion, lack of trained staff or providers and lack of equipment or supplies are cited as major reasons for not providing abortion (Figure 3.2). Lack of registration to provide abortion is also a major barrier to provision among private facilities and is reported by 33–56% of private facilities across the study states that offer postabortion care but not abortion (data not shown).

In addition to these barriers to provision, survey respondents also report a range of demand-related issues that they perceive as limiting women’s ability to seek out and obtain an abortion. Stigma is cited as a barrier by 45–74% of respondents, and other important barriers include cost (cited by 16–67%), family members’ disapproval (23–49%), lack of information about services (8–47%) and distance or transportation difficulties (8–44%; data not shown).

Almost all facilities that provide abortion-related services in the six study states report offering postabortion contraceptive services. Between 59% and 92% of facilities offer intrauterine contraceptive devices and 56–74% offer oral contraceptive pills (data not shown). However, the contraceptive information provided to women by many facilities is inadequate. Among facilities that offer contraceptive counseling, large proportions in all the study states do not cover certain key topics; for instance, only 8–27% report talking to patients about what to do in cases of method failure or incorrect use. In addition, the vast majority of facilities report they were out of stock of some contraceptive supplies at some point in the year prior to the survey (86–98%). Poor quality of care is also reflected in the substantial proportion of abortion-providing facilities that report requiring some women to adopt a contraceptive method as a prerequisite for receiving an abortion. In the five states with comparable data on this measure, this proportion ranges from 8% in Uttar Pradesh to 26% in Madhya Pradesh.§

Provision of Postabortion Care

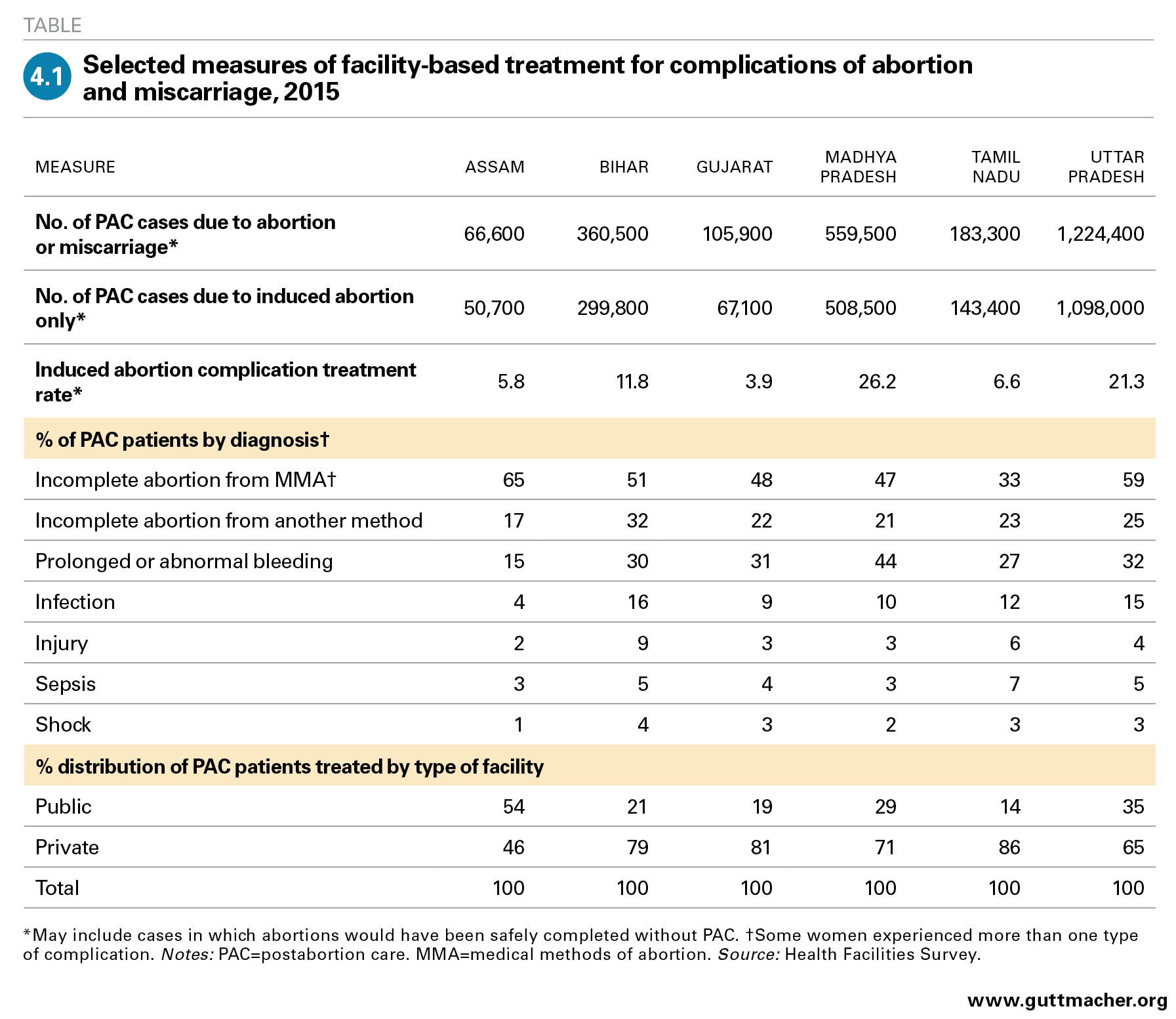

Like abortion care, treatment of complications arising from either unsafe induced abortion or miscarriage is an essential component of comprehensive reproductive health services. Among facilities offering any abortion-related services in the six study states, the proportion offering care for abortion complications ranges from 82% to 97% (data not shown). Although it is generally more common for facilities to offer postabortion care than to afford abortion, gaps in provision remain. The HFS provides an estimate of the annual number of women who obtain facility-based care for complications resulting from abortion or miscarriage in each of the six study states. This number ranges from 67,000 in Assam to 1,224,000 in Uttar Pradesh (Table 4.1). By estimating the number of patients treated for complications from miscarriages** and subtracting that from the total number treated for complications, we estimate the number treated for complications specifically related to induced abortion; for the six states, this number varies between 51,000 (Assam) to 1,098,000 (Uttar Pradesh). Although we cannot quantify how many women needing postabortion care do not obtain it, that number is likely to be substantial.45

Information on the types of complications women present with helps us understand the severity of their cases, as well as the types of interventions and medical resources they may need. In addition, such information may highlight areas where better education is needed. For example, some women who do not have full information on the use and effects of medical methods of abortion (MMA) may seek care unnecessarily for bleeding that is part of the normal process of a medication abortion.30 Knowing women’s diagnosis on admission helps to assess the extent to which the large numbers of women seeking postabortion care after obtaining MMA from informal-sector providers actually need treatment.

In the HFS, respondents were asked to estimate the proportion of women with each of the major types of complications, among all patients treated for complications related to either induced abortion or miscarriage in their facility. Because women may have more than one type of complication, proportions sum to more than 100% across the different types of complications. In all study states, incomplete abortion resulting from MMA is the most common complication, estimated to affect between 33% (in Tamil Nadu) and 65% (in Assam) of women obtaining care for complications. Prolonged or abnormal bleeding is the second most common complication type in four of the six states.

Prolonged bleeding and MMA-related incomplete abortion are likely to be overlapping categories, and estimates of the proportion of women treated for these types of complications probably include many cases in which abortions were done using MMA and would have been safely completed without need for further intervention if women had had the correct information and counseling. The proportion of women who receive needed treatment for incomplete abortion because of incorrect use of the method is likely small, given that MMA using mifepristone and misoprostol, when used correctly and within a nine-week gestational limit, is 95–98% effective.46

Another common complication among patients receiving postabortion care is incomplete abortion from methods other than MMA, which is reportedly experienced by 17–32% of women treated for complications in the six study states. Women presenting with this kind of complication may overlap with those who have prolonged bleeding but would not overlap with those experiencing incomplete abortion following MMA use.

Small proportions of postabortion care patients are estimated to be treated for severe complications, such as infection of the uterus and surrounding areas, sepsis, shock or physical injuries (e.g., perforation or laceration)—which are much more likely to result from induced abortion than from complications of miscarriages. Though these percentages are small, they represent hundreds of thousands of women per year experiencing severe complications across the six study states. For example, 4–16% of treated patients are estimated to be treated for infection of the uterus or surrounding areas (the most commonly treated serious complication), and that translates to a six-state total of approximately 330,000 cases each year. Some 2–9% of patients receiving postabortion care are treated for physical injuries, 3–7% for sepsis and 1–4% for shock. These four categories overlap to some extent because one woman may experience multiple complications at a time, so it is not possible to estimate precisely how many women are treated for severe complications overall. The estimate of 330,000 can be considered a minimum estimate of the annual number of such complications occurring in the six states combined. The majority of these severe cases likely originate among the group of women having nonfacility abortions using methods other than MMA.

Data from the HFS suggest that the private sector is the primary source of facility-based postabortion care in five of the states. Private facilities treat 86% of complication cases in Tamil Nadu, roughly 80% in Bihar and Gujarat, and about two-thirds in Madhya Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh; only in Assam is this proportion lower than 50%. Among facilities that do not offer postabortion care, the reasons for not doing so are much the same as the reasons for not offering abortion.

Incidence of Unintended Pregnancy

Unintended pregnancies result in abortions, unwanted births and miscarriages and are a key indicator of the need for contraception and the services and information that support effective use. Such pregnancies may indicate that women are not using any contraceptive method, are using a method inconsistently or incorrectly, or are using a relatively ineffective traditional method (typically periodic abstinence or withdrawal). Pregnancies may also be considered unintended for reasons unrelated to contraceptive use—for example, experience of sexual violence, changes in a woman’s or a family’s social or economic circumstances, or the advent of medical conditions that make pregnancy dangerous to a woman’s health. At the macro level, broad social and economic changes connected to the desire for smaller families may also affect the intention status of pregnancies and the need for contraceptive services; these include urbanization, improvements in women’s educational attainment and changing gender roles. Estimating the level of unintended pregnancy in the six focus states helps us understand the extent to which women need sexual and reproductive health services, including contraceptive and abortion-related care.

Data from the 2015–2016 National Family Health Survey (NFHS-4) help to frame the issue of unintended pregnancy and its connection to unmet need for contraception. Women in the six study states tend to have more children than they would ideally want, and this difference between total and wanted fertility is largest in Bihar, where women have an average of about one child more than they wanted (Table 5.1).47 Modern contraceptive use has not kept pace with the increasing the desire for small families in most states. In some states, in fact, the proportion of married women of reproductive age who use modern contraceptive methods has decreased; for instance, this proportion dropped in Gujarat from 57% to 43% between 2005–2006 and 2015–2016.47,48 Among married women in Assam and Uttar Pradesh, a substantial proportion of those who practice contraception (about 30%; data not shown) use traditional methods, which have relatively high failure rates.47 Among the six states, between 11% and 32% of married women of reproductive age have an unmet need for modern contraception—that is, they are able to become pregnant but wish to delay or avoid childbearing, and are not using a modern, effective method of contraception; they are thus at high risk for experiencing an unintended pregnancy. Information on sexual activity and contraceptive needs among unmarried women is very limited;49 however, given conservative social norms, sexually active unmarried women likely face considerable barriers to contraceptive use and may also experience substantial levels of unmet need and unintended pregnancy.50

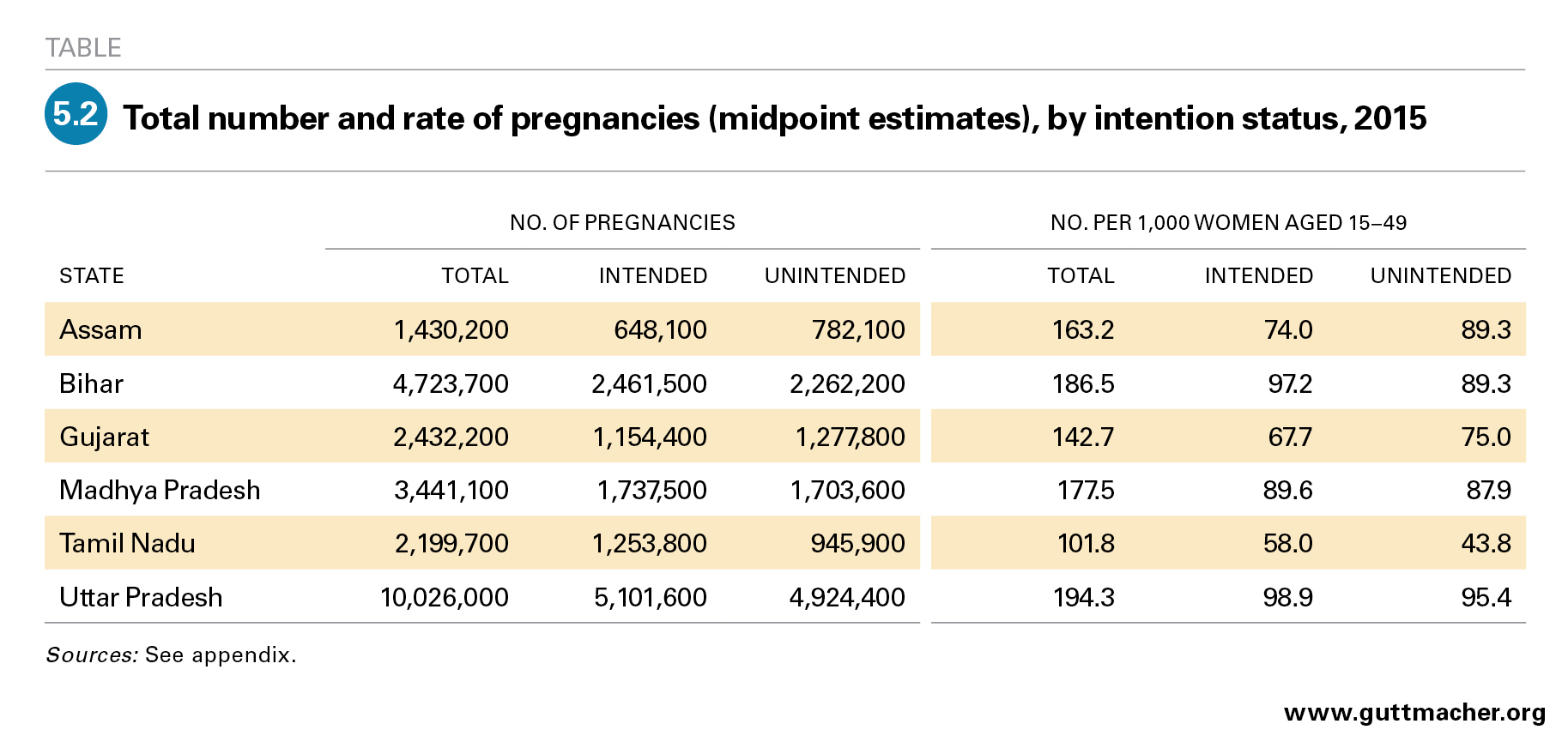

A reliable, representative estimate of abortion incidence allows us to estimate the incidence of all pregnancies in each study state. The total number of pregnancies is equal to the sum of all live births (from external sources;51 see appendix), abortions (estimated in this study) and miscarriages (including stillbirths; estimated based on global clinical studies). By summing these numbers, we arrive at an estimate of the total number of pregnancies occurring annually in each state; this total ranges from 1.4 million in Assam to 10.0 million in Uttar Pradesh (Table 5.2). The pregnancy rate (the annual number of pregnancies per 1,000 women aged 15–49) is highest in Uttar Pradesh (194) and lowest in Tamil Nadu (102).

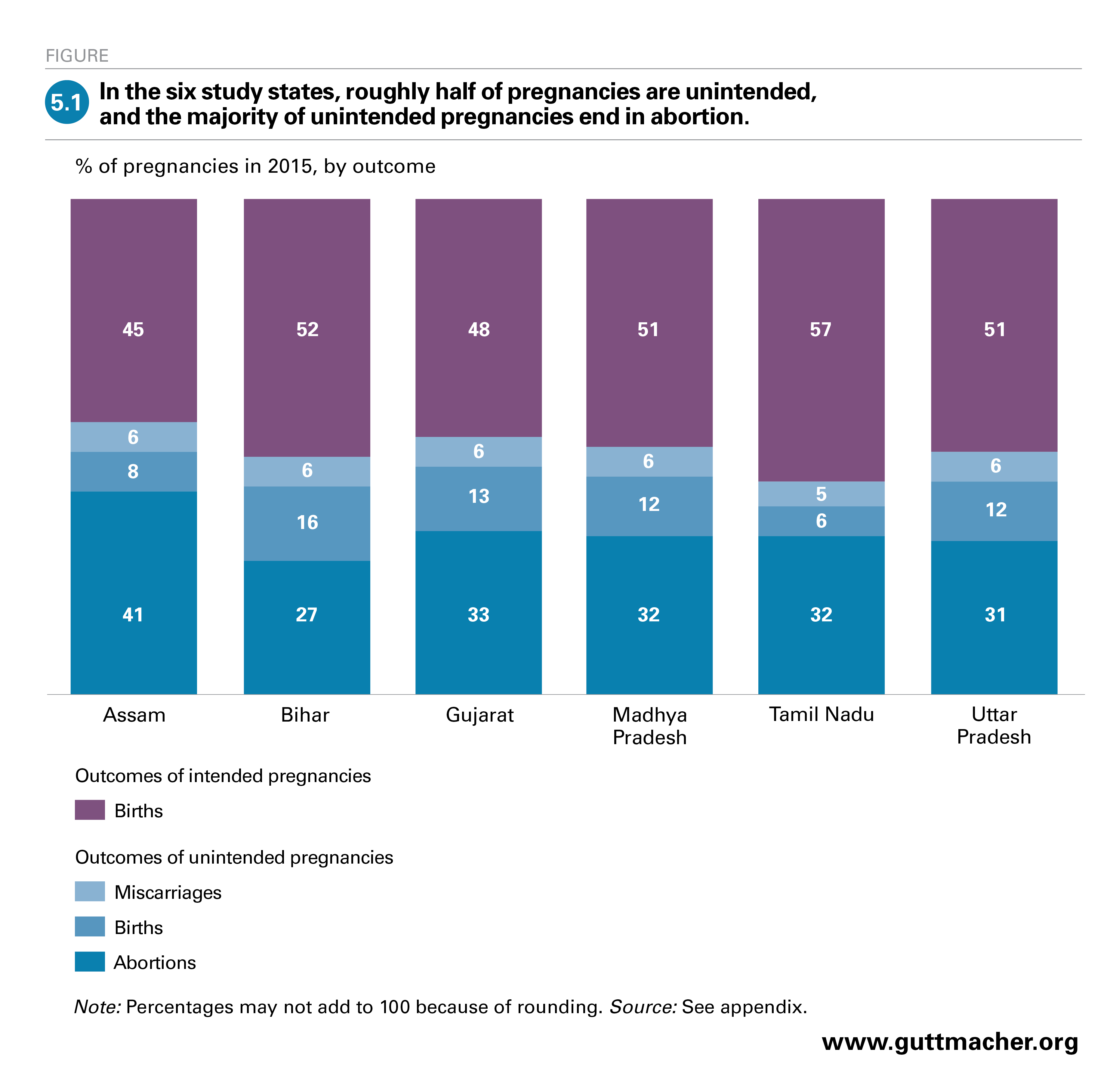

The number of unintended pregnancies is calculated by applying the proportion of births that are unwanted (based on NFHS-4 data on the total fertility and wanted total fertility rates for each state) to the number of live births in each state in 2015 and adding this to the number of abortions (which are assumed to result from mistimed or unwanted pregnancies) and the number of miscarriages†† resulting from unintended pregnancies. These calculations reveal that about half of all pregnancies (43–55%; Figure 5.1) in the six states are unintended, and unintended pregnancies number between 782,000 in Assam and 4,924,000 in Uttar Pradesh. Across the six states, this translates to rates of unintended pregnancy that range from 44 to 95 per 1,000 women of reproductive age. Between 26% and 41% of pregnancies overall end in abortion, and the majority of unintended pregnancies in all six states are terminated (55–75%; data not shown). This proportion is highest in Assam and Tamil Nadu, where about three in four unintended pregnancies result in abortion.

Implications of Findings for Policies and Practice

Some of the findings of our study are encouraging. For example, most facilities that provide induced abortion offer both medical methods of abortion (MMA) and surgical terminations, indicating these facilities can tailor care to each case. In addition, the large majority of facilities that offer abortion-related care also report providing contraceptive services intended to help women reduce their risk of having another unintended pregnancy. However, our study’s findings also highlight the clear need for improvements, and, in this chapter, we propose a range of interconnected strategies to improve access to safe, legal abortion and high-quality postabortion care. As the findings are broadly similar across states, the recommended strategies are applicable to all six states.

Expand facilities’ capacity to provide abortion

Our data indicate that a large proportion of facilities with the potential to provide safe, legal abortion care are not doing so. Lack of trained staff and lack of equipment and supplies are reported by nearly every type of facility as barriers to providing terminations, and lack of registration to provide abortion is a major barrier among private facilities.

Primary health centres (PHCs) represent the largest category of public facilities and are typically the first—and often the only—point of contact poor and rural women have with the health system; yet, very few currently offer any abortion-related care. It is important to ensure that these facilities, in particular, have the necessary staff, training, equipment and drugs to provide MMA, vacuum aspiration and basic postabortion care, as well as referral linkages to higher-level facilities. Expanding capacity at the PHC level would vastly expand the number of public facilities providing abortion, and it would increase access to services overall—particularly for the most disadvantaged groups of women, who may be unable to travel long distances or pay for services.

Compared with PHCs, greater proportions of higher level public facilities provide abortion, but barriers to provision remain common. For public facilities at all levels, adequate funding should be allocated through state Programme Implementation Plans to provide equipment and supplies on a regular basis and ensure they reach the facilities, and the budgeting system should be simplified to facilitate its accurate use.

To address private facilities’ lack of registration to provide abortion, district-level registration processes must be improved. Various organizations—for example, Action Research and Training for Health in Rajasthan and Ipas Development Foundation in Chhattisgarh, Madhya Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh—are working to increase District Level Committees’ ability to register private facilities.53,54 Other strategies to streamline the process include setting up online application options, as has been done in Uttar Pradesh.55 In addition, accelerated registration should be implemented for private facilities seeking approval to provide abortion using MMA only.

Policy changes and targeting of resources is needed at the national, state and district levels to increase the proportion of facilities able to provide induced abortion. We expect that the expansion of facility-based abortion care could greatly improve the overall quality of abortion provision by decreasing women’s reliance on the informal sector.

Broaden and strengthen the provider base

Expanding and improving facility-based services, as well as increasing access to care for the large numbers of women who currently terminate pregnancies outside of facilities, depends to a very large degree on having enough properly trained providers. State Departments of Health and Family Welfare and other government health agencies, as well as medical colleges, other centres responsible for training health workers at all levels, and NGOs, all have roles to play in increasing the number and quality of trained abortion providers.

Provider type and training. Parliamentary approval for midlevel providers—such as nurses and auxiliary nurse-midwives (ANMs), as well as practitioners trained in Indian systems of medicine with recognized qualifications—to offer MMA services would greatly expand the number of providers.56

In addition, new and practicing MBBS doctors should be supported to pursue abortion training and certification, and should receive ongoing training in medical best practices, which will help eliminate overuse of the most invasive surgical abortion techniques. Ensuring that providers receive the information they need may require increasing instruction on abortion techniques in medical schools and encouraging facilities to offer ongoing education for those already providing abortion.

Curricula for abortion providers at all levels should also include information about the country’s abortion laws, including women’s right to obtain abortion and sexual and reproductive health care more broadly. Providers who deny services to certain women may be acting on bias rather than following guidelines. Regular efforts should be made to ensure that health care providers and other facility staff do not impose unnecessary limitations on abortion provision.

Community-based health services. Several steps can be taken to expand abortion access at the community level. Accredited social health activists (ASHAs) and ANMs are often women’s first point of contact with the health system, and, although they do not perform abortions, they have the opportunity to help those who want to terminate a pregnancy find needed services. They should be trained to provide accurate information about India’s abortion laws and to direct women to providers of safe and legal services. With some additional effort, ASHAs and ANMs may also be trained to screen women for eligibility for MMA (for instance, by using the date of a woman’s last menstrual period to determine approximate gestation) and to advise women about their abortion options.57 In addition, community-based public health campaigns and other interventions are needed to provide women who obtain MMA from nonfacility providers with complete, accurate information on how to use this method; this might include widespread training of pharmacists. Such efforts would help prevent complications that arise from misuse and reduce unnecessary treatment for women experiencing the normal process of MMA.

Improve the quality of abortion-related services

The recommendations made up to this point to improve access to abortion and postabortion care will almost inevitably improve the quality of the care patients receive. However, our data point to several specific quality-of-care issues that should be addressed to ensure women are receiving acceptable, comprehensive services that meet World Health Organization standards.

Second-trimester abortion. Data from the six states indicate that a minority of abortion providers offer terminations beyond the first trimester. Second-trimester abortion is a vital component of high-quality abortion care, and the current shortfall in access to such terminations is a barrier that is likely to fall hardest on the most vulnerable women—those who are unable to seek earlier abortion because of poverty, difficulty traveling or lack of agency—as well as women who discover fetal anomalies or who develop health complications later in pregnancy. To the extent they have the capacity to do so, facilities should offer abortion to the full gestational limit allowed by law.

Adherence to medical best practices. The World Health Organization recommends the use of MMA or vacuum aspiration for most abortions and does not endorse use of dilatation and curettage (D&C),43 yet our data indicate D&C may still be commonly used in India. On the whole, providers may be relying on more invasive, riskier abortion techniques than are required or than would benefit their patients. Distribution of current guidelines and training in contemporary techniques led by respected physicians or professional associations would safeguard women’s health and well-being; in addition, increased reliance on less invasive techniques, when appropriate, could shorten women’s recovery time and reduce the cost of procedures.

Nonjudgmental and confidential services. Data from facility respondents indicate that stigmatization of abortion and sexuality plays a role in limiting provision of safe and legal services: Some women may encounter its effects both in the community at large and in the health facility itself. Providers must offer services in a nonjudgmental manner and to the full extent legally permitted; they can also help to protect their clients from the potential social costs of seeking an abortion by ensuring privacy and confidentiality in the services they offer, and by maintaining respectful, supportive attitudes. In addition, facilities can work to increase the confidentiality of health care visits, including by conducting consultations behind privacy screens and adopting recommended protocols for speaking to patients about sensitive issues.

Free or affordable services. The majority of women obtaining abortions in the six study states do so outside of the public sector, and therefore presumably pay out of pocket for services. Such costs are likely a barrier or a burden for many women. It is important to conduct research that collects women’s views on the accessibility and acceptability of abortion-related services in the public sector and their reasons for seeking care elsewhere. Simultaneously, to ensure quality of care for the most vulnerable subpopulations, the health system should work to ensure that free or low-cost public-sector abortion services in this sector are confidential, youth friendly and nonjudgmental. The needs of disadvantaged groups can also be met via the implementation or expansion of statewide programs such as Yukti Yojana in Bihar, which helps private providers become accredited and reimburses them for providing free first-trimester abortion and postabortion services to poor and low-income women.58

Contraceptive services for women obtaining abortion-related care. Although the large majority of facilities report offering contraceptive services to women obtaining abortion and postabortion care, it is clear that improvements are needed. Concerningly, a substantial minority of facilities report requiring some abortion patients to adopt a modern contraceptive method as a prerequisite for obtaining an abortion; it must be made clear to all providers that contraceptive services must always be provided on a voluntary basis. The relatively low uptake of contraceptives among abortion and postabortion care patients indicates other shortfalls in facilities’ approaches to provision. The Government of India’s guidance on postabortion family planning should be widely disseminated and implemented at all levels of health facilities to improve women’s access to and appropriate uptake of voluntary and comprehensive contraceptive care after an abortion.59

Public education about abortion. Findings from the HFS suggest that some women are not aware of the legal status of abortion and do not know where to obtain safe services. Addressing this dearth of knowledge will likely require a range of approaches. One approach likely to be effective and feasible is to expand the use of existing outreach and public education programs under the National Health Mission (NHM)60 by implementing existing media campaigns about abortion more widely and building on them by developing additional materials. One such mass media campaign was initiated by NHM in 2014 to disseminate information regarding the legality and availability of induced abortion at public and registered private sites; this campaign should be continued.44,61

Improve MMA services

MMA is safe and highly effective when the correct regimen is followed, and increased provision of this method, both in health facilities and in nonfacility settings, has improved access to abortion care. It has also likely reduced severe abortion-related morbidity: Available data on MMA drug distribution indicate that its use has been replacing the use of traditional and less-safe methods of abortion.62 Continuing to expand MMA provision would likely lead to further reductions in abortion morbidity.

At the same time, the implication in the HFS data that normal bleeding associated with MMA is sometimes misdiagnosed as a complication suggests that women who obtain MMA outside of facilities may be inadequately informed about such bleeding or may be given incorrect advice to seek treatment in facilities as soon as bleeding begins. In addition, the safety and effectiveness of MMA depend to some extent on the quality of the information given and the user’s adherence to the protocol.

Some strategies to facilitate proper use of MMA include ensuring combipacks have clear and simple instructions in multiple languages, as well as pictorial instructions for women with low literacy.44 The inserts should describe the regimen and expected symptoms, and should indicate where to go in case of complications. In addition, it may be beneficial to set up informational telephone helplines to help women who use MMA in a nonfacility setting do so safely. Helpline numbers could be printed prominently on MMA packaging and displayed at pharmacies.

Given that the majority of abortions in the six states use MMA obtained outside of a health facility, there is a particular need to find out more about the women who obtain MMA this way, their reasons for not using facility-based services, the type of provider they go to and their awareness of protocols. In addition, we need to know more about the extent to which women who seek treatment for complications after using MMA outside of a facility experience complications that require treatment and the costs they incur.

Improve access to and quality of postabortion care services

Many of the strategies for improving abortion provision will have the added benefit of improving postabortion care. For instance, increased training in abortion techniques will also bolster the provider skills needed for postabortion care; training about abortion law, countering stigma and providing confidential services will improve providers’ abilities to give high-quality care to patients experiencing abortion complications; and strategies to increase public-sector provision of abortion and postabortion care will go hand in hand.

Other steps can be taken to specifically address the need for improved postabortion care. HFS data suggest that most complications are comparatively minor, such as bleeding and other non–life-threatening complications resulting from use of MMA without professional guidance. With proper training, these types of complications can be addressed by relatively low-level medical staff, and specialized training of a wide provider base in treating these complications would greatly increase access to treatment. In addition, a small but notable proportion of women experience severe complications, so providers should be trained in best practices for treating physical injuries, infection, sepsis and shock caused by unsafe abortion.

Improve data collection

To obtain a more complete picture of abortion and postabortion care—and thus improve state governments’ ability to address gaps in and barriers to abortion-related services—state-level Departments of Health and Family Welfare need to expand data collection. Doing so will require making sure that the Government of India Health Management Information System more comprehensively captures abortion-related services provided in public and registered private facilities through improved implementation at state and local levels. Improving the process for registering private health facilities that provide only MMA and meet requirements for providing this service would create a formal channel for such facilities to report the services they provide, improving the overall coverage of official abortion statistics. Both public and private providers would need to be sensitized about the importance of keeping records on abortion data for reporting to state data systems and how to do so correctly and confidentially. Most importantly, the means for reporting on abortion service provision should be made straightforward and easy to implement.

Conclusion

Women in India have a range of health care needs related to pregnancy, and these vary according to the outcome of their pregnancy: For instance, women bringing a pregnancy to term, as well as some women who experience late miscarriages, need prenatal and delivery care; women experiencing complications of unsafe abortion need postabortion care; and women and their infants may need emergency maternal and newborn health services. Safe and legal abortion services are but one part of a package of necessary maternal health care, and strengthening and expanding abortion-related services is an important step toward bettering overall provision. Doing so will improve sexual and reproductive health in all states of India, in turn, raising the status of women and the well-being of individuals, families and communities.

Change must be achieved on multiple fronts. Our study’s findings for six focus states provide support for an array of policy and program actions, as well as for current and ongoing efforts to increase access to and quality of abortion-related services. In addition, our estimates of unintended pregnancy highlight the need for comprehensive contraceptive services—as part of the continuum of care for all women of reproductive age and, specifically, as part of postabortion and postpartum services—to prevent and address unintended pregnancy and unplanned childbearing. Whatever steps are taken must prioritize the needs of disadvantaged groups, including poor and rural women, ensuring that no groups are left behind.

Data and Methodology Appendix

This appendix provides a simplified explanation of the data sources and methods we used to arrive at our estimates of the incidence of abortion, the treatment rate for women experiencing abortion complications and the incidence of overall and unintended pregnancies. For more details, see our online methodology (under "supplementary materials" at www.thelancet.com/journals/langlo/article/PIIS2214-109X(17)30453-9).

Estimating induced abortion incidence

We estimated abortion incidence using a modified version of the abortion incidence complications method (AICM),63 an established method for indirectly estimating abortion incidence in countries where safe and unsafe abortion are prevalent but where official statistics are incomplete or unavailable. We modified the AICM for India by measuring each of three main components of total abortions separately: (1) facility-based abortions, (2) MMA using medications purchased outside of health facilities without the supervision of a facility provider and (3) other abortions occurring outside of health facilities without the supervision of a facility provider. Data available to measure the first two components are good-quality direct estimates, which are preferred to indirect estimates when such data can be obtained.

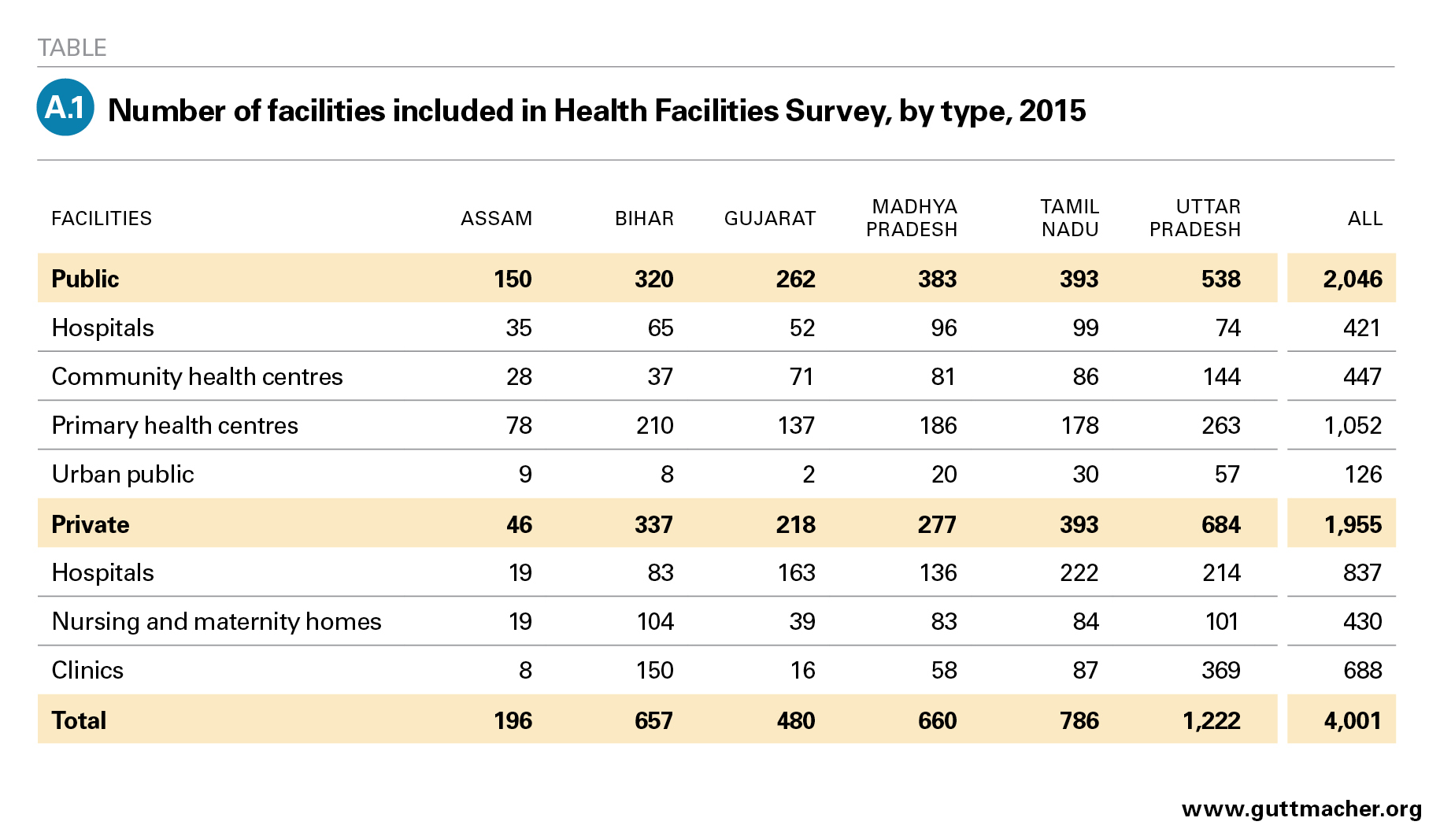

Facility-based abortions. The annual number of surgical and medical abortions obtained at public and private facilities comes from the Health Facilities Survey (HFS). This survey was conducted in a representative sample of 4,001 health facilities in six study states (Assam, Bihar, Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh, Tamil Nadu and Uttar Pradesh; Appendix Table 1). These states account for about 45% of India’s population of women of reproductive age and were chosen to represent regional variation in the country. The HFS was administered to senior health care professionals knowledgeable about the provision of abortion-related services at their facility.‡‡ Numbers of abortions were weighted to estimate state levels of public- and private-sector facility-based abortions. National and state totals of abortions obtained from large NGO providers were compiled separately and then summed with HFS estimates to produce total facility-based abortion estimates for each state.

Nonfacility MMA. We used state-level data on for-profit drug sales and nonprofit distribution of combipacks (combined mifepristone and misoprostol) and mifepristone-only pills in 2015 to estimate the number of MMAs obtained outside of health facilities. We did not include misoprostol-only sales because the drug has uses unrelated to abortion, and it was not possible to estimate the quantity used specifically to induce abortions. The broad availability of the combipack implies that use of misoprostol alone to induce abortion is likely to be relatively low. However, if misoprostol is still used by a small proportion of women, abortion incidence will be slightly underestimated.

We applied the following adjustments to the for-profit MMA drug sales data to arrive at the corresponding number of abortions using this method:

- We adjusted the mifepristone-only data to account for the fact that women may use more than one pill to induce an abortion. We assumed that 80% of women who purchase mifepristone alone (i.e., not in a combipack) use one 200-mg pill, 10% use two and 10% use three.64,65

- We averaged the for-profit sales data among groups of states because some states are focal points for distribution to other states, and sales of MMA in each state do not necessarily reflect use in that state. For each group of states, an average number of MMA packets per 1,000 women of reproductive age was calculated and applied to the appropriate study state’s population to estimate the for-profit sales of MMA drugs likely to be used in the state.

- We also reduced the estimated number of MMA sales to account for cross-border black market sales to the adjacent countries of Bangladesh and Nepal.66,67

- IMS Health reports that their drug sales are 95% complete,68 so we inflated for-profit drug sales numbers by 5% to account for the missing data.

We then summed MMA distributed by nonprofits and the adjusted total sold in for-profit venues, and made the following adjustments:

- On the basis of available studies, we reduced the total by 10% to account for the proportion of MMA drugs likely lost to wastage.69,70

- To avoid double-counting women who attempted an abortion using MMA before obtaining a facility-based abortion, we reduced the estimated number by an additional 5% of facility-based abortions.71

Finally, we subtracted MMA provided in private and NGO facilities and that given by prescription from public facilities to obtain the number of abortions using MMA provided in nonfacility settings in 2015. This step was necessary because MMA administered in public facilities (i.e., provided directly from the doctor and not via prescription) is supplied through government tenders and is not included in for-profit or nonprofit drug sales data.

Nonfacility abortions using methods other than MMA. There are no direct sources of information on the number of abortions occurring outside of facilities that use methods other than MMA, so we estimated these indirectly. Two community-based studies conducted in 2009 provide estimates of the proportion of all women having abortions who do so outside of a facility using a method other than MMA: 8% in Maharashtra and 6% in Rajasthan.32,33 The proportion of women seeking these types of abortions is expected to have declined with the rise in MMA use since those studies took place. We therefore adjusted the average of the estimates from these two studies downward to account for rising MMA use (based on the rate of increase in MMA drug sales between 2009–2010 and 2015) and estimated the proportion in 2015 to be 5% (a drop of approximately 30% over these six years).

Sensitivity analysis and estimate ranges. Because we made several assumptions that introduced a degree of uncertainty to our estimates of both MMA and other types of abortion occurring outside of facilities, we performed sensitivity analyses. On the basis of available literature and expert opinions, we established lower and upper bounds for each assumption described above. In addition, using the sample design of the HFS, we calculated standard errors around the number of facility-based abortions to create confidence intervals around the HFS estimates. Using the results of the sensitivity analysis, we estimated a range around the total number of abortions.

Calculating abortion rates

The abortion rate is defined as the number of abortions per 1,000 women aged 15–49 in a given year. This study provides the estimated number of abortions for 2015, and state-specific populations of women of reproductive age were estimated using projections based on the rate of population growth between the 2001 and 2011 India Censuses, assuming the age distribution remained stable between 2011 and 2015.72

Estimating the incidence of unintended pregnancy and total pregnancy

The total number of pregnancies is the sum of the numbers of births, abortions and miscarriages. Abortion estimates are described above and estimates of the number of live births come from the United Nations Population Division.§§51 The number of miscarriages is based on the biological pattern of pregnancy loss, and is estimated to be 20% of live births plus 10% of abortions.73,74 Planned and unplanned births were calculated by applying estimates of the proportion of the total fertility rate that is unwanted (from the 2015–2016 National Family Health Survey) to 2015 state-specific estimates of the number of live births. Planned births and miscarriages resulting from intended pregnancies (estimated to equal 20% of planned births) were summed to estimate the number of intended pregnancies. Abortions, unwanted births and miscarriages that resulted from unintended pregnancies (estimated to be 20% of unplanned births and 10% of abortions) were summed to estimate the number of unintended pregnancies.

FOOTNOTES

*In this study, MMA refers primarily to the combined use of misoprostol and mifepristone, whether the tablets are packaged separately or together (in a "combipack"); it excludes misoprostol-only abortions.

†In 2010, the MoHFW’s Comprehensive Abortion Care Training and Service Delivery Guidelines for providing comprehensive abortion care indicated in a footnote that MMA up to 63 days’ gestation is safe.27 However, amendments to the MTP Act that would reflect this modification are still awaiting passage in Parliament.

‡Including a small proportion provided by NGO facilities.

§In Assam, this question was worded slightly differently; therefore, data from that state are not comparable to those from other states.

**Assuming only later-term miscarriages are treated in facilities and that the percentage of women experiencing such miscarriages who obtain care in facilities is equal to the percentage of women who give birth in a facility.

††A small proportion of abortions (4%, according to one U.S. study52) arise from wanted pregnancies—for example, because of fetal anomalies or maternal health issues. However, we did not adjust for this factor because this proportion is small and because errors occur in the opposite direction (such as underreporting of unintended pregnancies due to rationalization of past pregnancies after the fact).

‡‡Public facilities were grouped into hospitals (rural, district, civil, sub-divisional, municipal, tertiary, railway, Employees’ State Insurance Corporation, tea estate, military and refinery hospitals, and public medical colleges), CHCs (first referral units and non–first referral units), PHCs (those that are and are not open 24-7, and block PHCs) and a relatively small number of urban public facilities (urban health centres, urban family welfare centers and a few other types of facilities). Private facilities were grouped into hospitals (multispecialty hospitals, specialized hospitals and private medical colleges), nursing and maternity homes, and clinics.

§§Estimates of the number of live births for individual states were developed by IIPS. These estimates integrate the United Nations 2015 estimate of births in India with data from national sources, such as the Sample Registration System, to capture state-specific variation in fertility level, while ensuring that the national total number of births was consistent with the United Nations national estimate.

REFERENCES

1. Government of India, Medical Termination of Pregnancy Act, Act No. 34, 1971.

2. Pradhan MR et al., Unintended Pregnancy, Abortion and Postabortion Care in Assam, India—2015, New York: Guttmacher Institute, 2018.

3. Stillman M et al., Unintended Pregnancy, Abortion and Postabortion Care in Bihar, India—2015, New York: Guttmacher Institute, 2018.

4. Sahoo H et al., Unintended Pregnancy, Abortion and Postabortion Care in Gujarat, India—2015, New York: Guttmacher Institute, 2018.

5. Hussain R et al., Unintended Pregnancy, Abortion and Postabortion Care in Madhya Pradesh, India—2015, New York: Guttmacher Institute, 2018.

6. Alagarajan M et al., Unintended Pregnancy, Abortion and Postabortion Care in Tamil Nadu, India—2015, New York: Guttmacher Institute, 2018.

7. Shekhar C et al., Unintended Pregnancy, Abortion and Postabortion Care in Uttar Pradesh, India—2015, New York: Guttmacher Institute, 2018.

8. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MoHFW), Health and Family Welfare Statistics of India 2015, New Delhi: MoHFW, Statistics Division, 2015.

9. Banerjee S, Indirect estimation of induced abortion in India, working paper, New Delhi: Ipas Development Foundation, 2012.

10. Office of the Registrar General and Census Commissioner, India, Annual Health Survey 2012–13 Fact Sheet: Assam, no date, http://www.censusindia.gov.in/vital_statistics/AHSBulletins/AHS_Baselin….

11. Office of the Registrar and Census Commissioner, Annual Health Survey 2012–13 Fact Sheet: Bihar, no date, http://www.censusindia.gov.in/vital_statistics/AHSBulletins/AHS_Factshe….

12. Office of the Registrar and Census Commissioner, Annual Health Survey 2012–13 Fact Sheet: Madhya Pradesh, no date, http://www.censusindia.gov.in/vital_statistics/AHSBulletins/AHS_Factshe….

13. Office of the Registrar General and Census Commissioner, India, Annual Health Survey 2012–13 Fact Sheet: Uttar Pradesh, no date, http://www.censusindia.gov.in/vital_statistics/AHSBulletins/AHS_Factshe….

14. Sedgh G et al., Abortion incidence between 1990 and 2014: global, regional, and subregional levels and trends, Lancet, 2016, 388(10041):258–267, doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30380-4.

15. Jones RK and Kost K, Underreporting of induced and spontaneous abortion in the United States: an analysis of the 2002 National Survey of Family Growth, Studies in Family Planning, 2007, 38(3):187–197.

16. Sedgh G and Henshaw SK, Measuring the incidence of abortion in countries with liberal laws, in: Singh S, Remez L and Tartaglione A, eds., Methodologies for Estimating Abortion Incidence and Abortion-Related Morbidity: A Review, New York: Guttmacher Institute and International Union for the Scientific Study of Population, 2010, pp. 23–33.

17. Rossier C, Estimating induced abortion rates: a review, Studies in Family Planning, 2003, 34(2):87–102.

18. International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS), District Level Household and Facility Survey (DLHS-3), 2007–08: India, Mumbai: IIPS, 2010.

19. Stillman M et al., Abortion in India: A Literature Review, New York: Guttmacher Institute, 2014, www.guttmacher.org/report/abortion-india-literature-review.

20. IIPS and Macro International, National Family Health Survey (NFHS-2), India, 1998–99, Mumbai: IIPS, 2000.

21. Chhabra R and Nuna S, Abortion in India: An Overview, New Delhi: Veerenda Printers, 1994.

22. Duggal R and Ramachandran V, Abortion Assessment Project–India: Summary and Key Findings, Mumbai: Centre for Enquiry into Health and Allied Themes (CEHAT) and Healthwatch, 2004.

23. Duggal R and Ramachandran V, The Abortion Assessment Project–India: key findings and recommendations, Reproductive Health Matters, 2004, 12(24 Suppl.):122–129.

24. Krishnamoorthy S et al., Pregnancy Outcome In Tamilnadu: A Survey With Special Reference to Abortion Complications, Cost And Care, Coimbatore, India: Department of Population Studies, Bharathiar University, 2004.

25. Saha S, Duggal R and Mishra M, Abortion in Maharashtra: Incidence, Care and Cost, Mumbai: CEHAT, 2004.

26. Center for Reproductive Rights, The world’s abortion laws 2017, no date, http://worldabortionlaws.com/map/.

27. MoHFW, Comprehensive Abortion Care: Training and Service Delivery Guidelines, New Delhi: MoHFW, 2010.

28. Government of India, The Medical Termination of Pregnancy (Amendment) Act, 2002.

29. Government of India, The Medical Termination of Pregnancy Rules (Amendment), 2003.

30. Powell-Jackson T et al., Delivering medical abortion at scale: a study of the retail market for medical abortion in Madhya Pradesh, India, PLOS One, 2015, 10(3):e0120637, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0120637.

31. Winikoff B and Sheldon W, Use of medicines changing the face of abortion, International Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 2012, 38(3):164–166.

32. Jejeebhoy S et al., Increasing Access to Safe Abortion in Rural Maharashtra: Outcomes of a Comprehensive Abortion Care Model, New Delhi: Population Council, 2011.

33. Jejeebhoy S et al., Increasing Access to Safe Abortion in Rural Rajasthan: Outcomes of a Comprehensive Abortion Care Model, New Delhi: Population Council, 2011.

34. Collumbien M, Mishra M and Blackmore C, Youth-friendly services in two rural districts of West Bengal and Jharkhand, India: definite progress, a long way to go, Reproductive Health Matters, 2011, 19(37):174–183, doi:10.1016/S0968-8080(11)37557-X.

35. IIPS and Macro International, India Facility Survey (Under Reproductive and Child Health Project—Phase II, 2003), Mumbai: IIPS, 2005, http://rchiips.org/pdf/rch2/National_Facility_Report_RCH-II.pdf.

36. Statistics Division, MoHFW, Rural Health Statistics in India 2012, New Delhi: MoHFW, 2013.

37. Government of India, Amendment to the Pre-Conception and Pre-Natal Diagnostic Techniques (Prohibition of Sex Selection) Act, 2003.

38. Government of India, Pre-Natal Diagnostic Techniques (Regulation and Prevention of Misuse) Amendment Act, No. 14 of 2003.

39. Nidadavolu V and Bracken H, Abortion and sex determination: conflicting messages in information materials in a District of Rajasthan, India, Reproductive Health Matters, 2006, 14(27):160–171, doi:10.1016/S0968-8080(06)27228-8.

40. Shidhaye PR et al., Study of knowledge and attitude regarding prenatal diagnostic techniques act among the pregnant women at a tertiary care teaching hospital in Mumbai, Journal of Education and Health Promotion, 2012, 1:36, doi:10.4103/2277-9531.102049.

41. Yasmin S et al., Gender preference and awareness regarding sex determination among antenatal mothers attending a medical college of eastern India, Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 2013, 41(4):344–350, doi:10.1177/1403494813478694.

42. National Health Mission, Comprehensive Abortion Care Services, New Delhi: Maternal Health Division, MoHFW, 2014.

43. World Health Organization (WHO), Clinical Practice Handbook for Safe Abortion, Geneva: WHO, 2014.

44. Sheriar N, formerly of the Federation of Obstetrics and Gynecological Societies of India, Mumbai, personal communication, Sep. 2, 2017.

45. Singh S et al., Abortion Worldwide 2017: Uneven Progress and Unequal Access, Guttmacher Institute, 2018, doi:10.1363/2018.29199.

46. Creinin M and Gemzell-Danielsson K, Medical abortion in early pregnancy, in: Paul M et al., eds., Management of Unintended and Abnormal Pregnancy: Comprehensive Abortion Care, Hoboken, NJ, USA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009, pp. 111–134.

47. IIPS and ICF, National Family Health Survey (NFHS-4), India, 2015–16, Mumbai: IIPS, 2017.

48. IIPS and Macro International, National Family Health Survey (NFHS-3), India, 2005–06, Mumbai: IIPS, 2007.

49. IIPS and Population Council, Youth in India: Situation and Needs 2006–2007, Mumbai: IIPS and Population Council, 2010.

50. Jejeebhoy SJ et al., Experience seeking abortion among unmarried young women in Bihar and Jharkhand, India: delays and disadvantages, Reproductive Health Matters, 2010, 18(35):163–174, doi:10.1016/S0968-8080(10)35504-2.

51. Population Division, United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, World Population Prospects, the 2015 Revision, New York: United Nations, 2016, https://esa.un.org/unpd/wpp/.

52. Finer LB and Henshaw SK, Disparities in rates of unintended pregnancy in the United States, 1994 and 2001, Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 2006, 38(2):90–96.

53. Iyengar SD, Action Research and Training for Health, Udaipur, Rajasthan, India, personal communication, Sep. 4, 2018.

54. Banerjee SK, Ipas Development Foundation, New Delhi, personal communication, Sep. 5, 2018.

55. National Health Mission Uttar Pradesh, Approval of private clinics for Comprehensive Abortion Care (CAC) services, 2017, http://cacuttarpradesh.in/registration.php.

56. MoHFW, Draft Medical Termination of Pregnancy (Amendment) Bill, 2014.

57. WHO, Health Worker Roles in Providing Safe Abortion Care and Post Abortion Contraception, Geneva, WHO, 2015.

58. Government of Bihar and National Rural Health Mission, Guidelines for Accreditation of Private Sites for Provision of Comprehensive Abortion Care Services, Patna, India: Government of Bihar, 2011.

59. Family Planning Division, MoHFW, Post Abortion Family Planning: Technical Update, New Delhi: Government of India, 2016.

60. MoHFW, Ensuring Access to Safe Abortion and Addressing Gender Biased Sex Selection, New Delhi: MoHFW, 2015.

61. Ipas Development Foundation, National Health Mission—mass media campaign on making abortion safer, video, 2015, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QPc4NSZ48sg.

62. Banerjee S, Abortion method, provider, and cost in transition: experience of Indian women seeking abortion over the last twelve years (2004–2015), paper presented at the International Population Conference, Cape Town, South Africa, Oct. 29–Nov. 4, 2017.

63. Singh S, Prada E and Juarez F, The Abortion Incidence Complications Method: a quantitative technique, in: Singh S, Remez L and Tartaglione A, eds., Methodologies for Estimating Abortion Incidence and Abortion-Related Morbidity: A Review, New York: Guttmacher Institute, 2010, pp. 71–98.

64. Sheriar N, formerly of the Federation of Obstetrics and Gynecological Societies of India, Mumbai, personal communication, Aug. 2, 2017.

65. Elul B et al., Are obstetrician-gynecologists in India aware of and providing medical abortion?, Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology India, 2006, 56(4):340–345.

66. Hossain A, Bangladesh Association for Prevention of Septic Abortion, Dhaka, Bangladesh, personal communication, Dec. 1, 2016.

67. Puri M, Center for Research on Environment, Health and Population Activities, Patan, Nepal, personal communication, Dec. 5, 2016.

68. Kumar M, IMS Health: a brief introduction, slide presentation, Mumbai: IMS Health, 2014.

69. Vlassoff M et al., Cost-effectiveness of two interventions for the prevention of postpartum hemorrhage in Senegal, International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics, 2016, 133(3):307–311.

70. Seligman B and Xingzhu L, Policy and Financing Analysis of Selected Postpartum Hemorrhage Interventions: Country Summary, Rockville, MD, USA: Abt Associates, 2006.

71. Kumar R et al., Unsuccessful prior attempts to terminate pregnancy among women seeking first trimester abortion at registered facilities in Bihar and Jharkhand, India, Journal of Biosocial Science, 2013, 45(2):205–215, doi:10.1017/S0021932012000533.

72. IIPS, special tabulations of population growth data from the 2001–2011 Censuses.

73. Bongaarts J and Potter R, Fertility, Biology, and Behavior: An Analysis of the Proximate Determinants, New York: Academic Press, 1983.

74. Harlap S, Shiono P and Ramcharan S, A life table of spontaneous abortions and the effects of age, parity and other variables, in: Porter I and Hook E, eds., Human Embryonic and Fetal Death, New York: Academic Press, 1980, pp. 145–158.

Suggested Citation

Singh S et al., Abortion and Unintended Pregnancy in Six Indian States: Findings and Implications for Policies and Programs, New York: Guttmacher Institute, 2018, https://www.guttmacher.org/report/abortion-unintended-pregnancy-six-sta….

Acknowledgments

This report is part of a larger study titled Unintended Pregnancy and Abortion in India (UPAI), which was conducted to provide much-needed information on the incidence of abortion and pregnancy, as well as access to and quality of safe abortion services, in six Indian states.

The authors thank the technical advisory committee that provided guidance throughout the project. It was chaired by Purushottam Kulkarni, formerly of Jawaharlal Nehru University, and its members were Dinesh Agrawal, independent consultant; Sushanta Banerjee, Ipas Development Foundation (IDF); Manju Chhugani, Jamia Hamdard University; Kurus Coyaji, King Edward Memorial Hospital; Ravi Duggal, International Budget Partnership; Sharad Iyengar, Action Research and Training for Health; Sunitha Krishnan, St. John’s National Academy of Health Sciences; Mala Ramanathan, Sree Chitra Tirunal Institute for Medical Sciences and Technology; T.K. Roy, independent consultant; Nozer Sheriar, Hinduja Healthcare Surgical and Holy Family Hospitals; Leela Visaria, Gujarat Institute of Development Research; and Ministry of Health and Family Welfare representatives Rakesh Kumar, Manisha Malhotra, Dinesh Biswal, Sumita Ghosh and Veena Dhawan.

The authors are grateful to the data collection agencies that fielded the Health Facilities Survey in the six states and to the field investigators who conducted the interviews. They also thank the survey respondents, who contributed their time and expertise in providing essential information on abortion services in their facilities.

The following colleagues provided much-appreciated guidance, information or external data along the way: Kalpana Apte, Family Planning Association of India (FPAI); Alok Banerjee and Sudha Tewari, Parivar Seva Santha; Amit Bhanot and Mahesh Kalra, Hindustan Latex Family Planning Promotion Trust (HLFPPT); Todd Callahan, Christopher Purdy and Michele Thorburn, all of DKT International; V.S. Chandrashekhar, Foundation for Reproductive Health Services India; Kathryn Church and Barbara Reichwein, Marie Stopes International, London; Altaf Hossain, Bangladesh Association for the Prevention of Septic Abortion; Vivek Malhotra and Sunitha Bhat, Population Health Service India; Hanimi Reddy Modugu, formerly of HLFPPT; Armin Neogi, formerly of FPAI; Ram Parker, Janani; Mahesh Puri, Center for Research on Environment Health and Population Activities, Nepal; Faujdar Ram, formerly of the International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS); and Usha Ram and L. Ladusingh, IIPS.