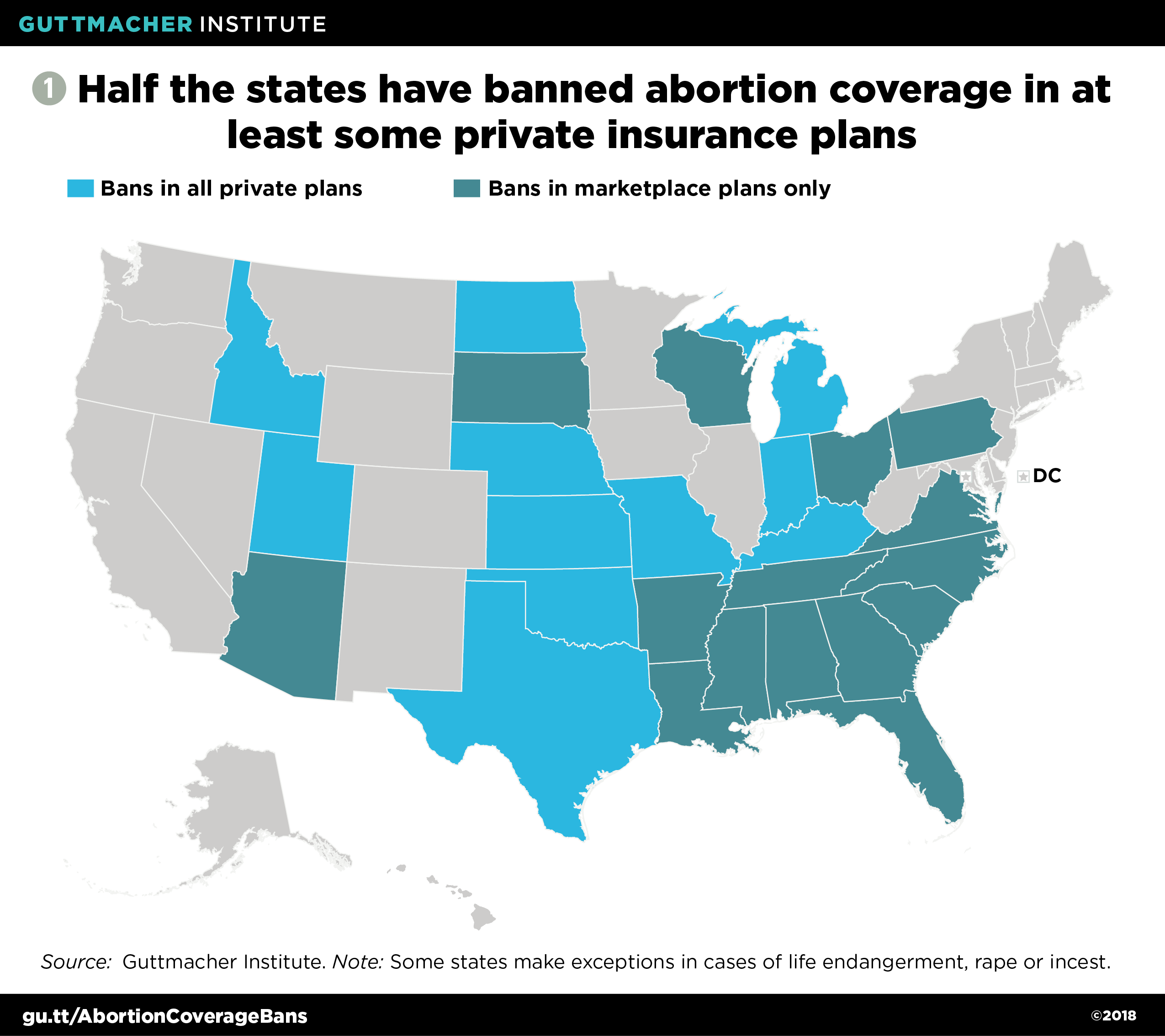

One long-term goal of antiabortion conservatives has been to eliminate abortion coverage in all private insurance plans, just as they have eliminated abortion coverage under Medicaid in most parts of the United States already. In a number of the most conservative states, antiabortion policymakers have pursued their goal directly: Eleven states have outright bans on abortion coverage in all private insurance plans regulated by the state, and many additional states have bans for segments of the insurance market, such as in Affordable Care Act (ACA) marketplace plans or plans for public employees (see figure 1).1

At the federal level, antiabortion policymakers have used federal funding as a pretext for proposed restrictions. First, they argue that antiabortion taxpayers should not have to violate their religious or moral convictions by helping to fund insurance plans that cover abortion. Second, they insist that no compromise policy can satisfy taxpayers’ concerns. For example, they claim that the ACA’s current policy—under which federal dollars cannot pay for abortion coverage, but segregated funds from enrollees’ premium payments can—indirectly allows federal dollars to fund abortion by "freeing up" other resources.

Conservatives’ dogged commitment to their goal of eliminating private insurance coverage of abortion is a clear threat to the ability of millions of people to access and afford abortion care. Moreover, antiabortion conservatives have turned their demand into a roadblock to efforts that might lower overall premiums and deductibles, improve consumers’ choice of health plans, or otherwise improve on the ACA and expand health insurance coverage in the United States.

Social conservatives view federal funding as leverage for eliminating private insurance coverage of abortion. For more than 40 years, antiabortion conservatives have used the specter of federal funding for abortion to justify the Hyde Amendment, which bans federal funding for abortion under Medicaid, except in cases of life endangerment, rape or incest. It has been an effective tactic: No state can afford to give up federal Medicaid funds, so abortion is not covered in most states’ Medicaid programs. It is only because the federal government cannot prevent states from funding abortion coverage separately with state dollars that Medicaid enrollees in 16 states have abortion coverage available.2

Antiabortion conservatives see their past success in restricting abortion coverage under Medicaid and other federal programs as a template for imposing restrictions on private insurance coverage as well. The ACA provided them with an opening, because it established substantial new federal subsidies for many private insurance plans, which plans and consumers cannot afford to turn down. Individual states would not be in a position to preserve abortion coverage if a federal restriction on private insurance plans were enacted, because there would not be any state program or money involved. Rather, a state would need to set up a new program purely for abortion coverage for otherwise privately insured people—an extreme step away from the status quo, where many states are neutral on the question of abortion coverage in private insurance.

That use of federal money is not really the issue is made clear by the antiabortion movement’s rejection of the ACA’s current policy, which allows insurance plans to cover abortion but requires them to wall off federal dollars from private dollars to ensure that no federal money pays for abortion coverage or services. Only a small number of antiabortion lawmakers agreed to that policy as a compromise to get the ACA enacted. Those members of Congress were swiftly rejected by the broader antiabortion movement, which falsely argued at that time and ever since that the ACA was a massive federal subsidy for abortion.

Antiabortion conservatives have fought relentlessly for a different policy: to bar any health insurance plan that receives even a dime of federal money from covering abortion. They pushed for this restriction throughout the debate over ACA enactment, in subsequent stand-alone legislation, during the effort to "repeal and replace" the ACA in 2017, and in debating new federal investment to lower insurance premiums and expand consumer options. The specific language proposed has varied, and most recently, congressional conservatives have argued that they "merely" want to apply the Hyde Amendment language to private insurance plans. However, the bottom line is that the antiabortion movement would not propose or accept any language that would fail to accomplish the goal it has consistently pursued.

New coverage restrictions would make it harder or even impossible for people to buy abortion coverage. To be clear, private coverage of abortion is already highly restricted in the United States because of a slew of state-level restrictions and the burdensome requirements for segregated funding written into the ACA. Even when abortion coverage is permitted by law, it is often unavailable: For example, analyses of ACA marketplace plans by the Guttmacher Institute and the Kaiser Family Foundation have found that in states that allow abortion coverage, consumers in many counties and some entire states have no plan choices that actually include that coverage.3,4

Antiabortion policymakers are seeking to make this situation worse with new restrictions. For example, if they succeed in barring the use of federal funds (such as federal subsidies to help enrollees afford premiums and cost sharing) for ACA marketplace plans that cover abortion, that would effectively eliminate abortion coverage in marketplace plans altogether because those federal subsidies are too important for consumers to pass up. If Congress were to place that type of ban on federal funds that go to all individual market plans and to employer-based plans (such as many "reinsurance" proposals, which would protect insurance plans against unexpected costs and thereby lower premiums), it would effectively eliminate abortion coverage more broadly. Antiabortion policymakers plan to keep adding restrictions to as many parts of the health insurance market as possible, until there are no insurance plans left that can cover abortion or are willing to do so.

New federal restrictions on plans that cover abortion would be particularly harmful in the four states—California, New York, Oregon and Washington—that have worked to protect abortion rights and access by requiring private insurance plans they regulate to cover abortion.5 A federal restriction would place these states in an untenable position: The state might be forced to reverse or stop enforcing its abortion coverage requirement, or else state residents and health plans might find themselves unable to receive federal subsidies—a situation that would negate Congress’s attempts to make private insurance coverage more affordable.

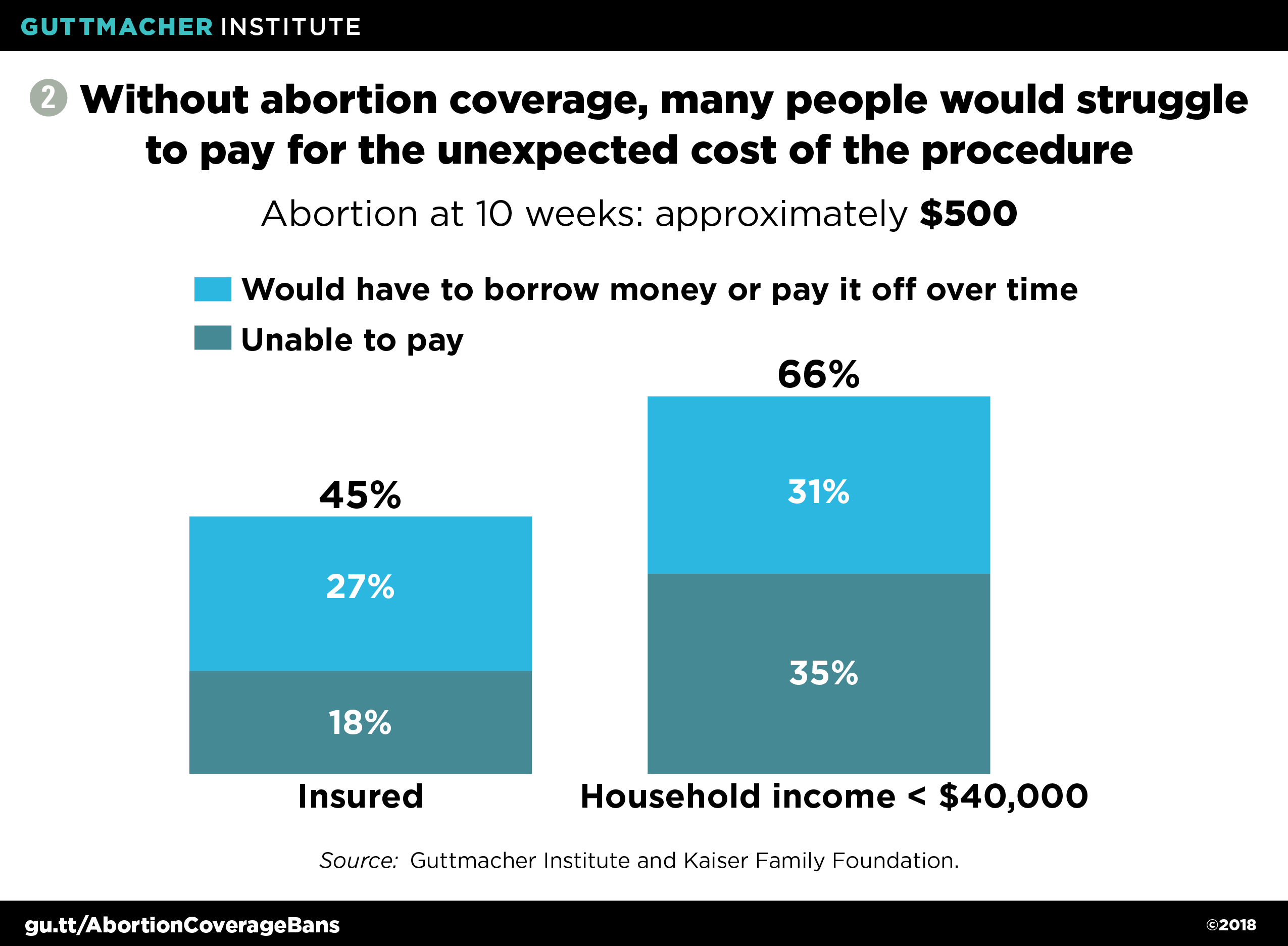

Barriers to abortion coverage harm patients. Whether health insurance covers abortion has direct financial implications for patients, particularly those with lower incomes.6 About four in 10 privately insured abortion patients use their insurance to pay for the procedure.7 An abortion at 10 weeks’ gestation typically costs around $500, and the cost is considerably higher for abortions later in pregnancy.8 Many patients may be unable to pay such an amount out of pocket: According to another Kaiser survey, about one-third of lower income people would be unable to pay for an unexpected $500 medical bill, and roughly another third would have to borrow money or charge the expense on a credit card and pay it back over time (see figure 2).9

For the six in 10 privately insured abortion patients who pay out of pocket, it is unclear what specific hurdles they face. Some patients may have health insurance plans that do not cover abortion, or they may not know whether their plan covers the procedure. Others have high deductibles that must be met before their plan covers any expenses. In some cases, a patient’s health plan may not include her abortion provider in its network. And given the stigma that surrounds abortion, some patients may opt not to use their insurance coverage because they worry that their insurer, employer, spouse or parent might find out about the abortion. Abortion coverage restrictions contribute directly or indirectly to most of these barriers.

To cover the out-of-pocket cost for the procedure if they do not have abortion coverage—plus the costs for things like travel, lodging, child care and time off from work—many low-income patients put off paying utility bills or rent, or buying food for themselves and their children.10 Others receive financial help from family members, clinics or charities, or sell their personal belongings.7,10 Moreover, taking time to find the money for an abortion can lead to delays in obtaining care, which in turn can lead to additional costs and delays. As a pregnancy progresses, the cost of an abortion increases, the number of providers who offer abortion services decreases,8 and more legal restrictions on abortion might apply.11

In other cases, not having abortion coverage can mean not being able to obtain abortion care at all, and the result is an unplanned and often unwanted birth. The reasons people give for seeking an abortion are informative: Most abortion patients say they cannot afford a child or another child, and that having a baby would interfere with their work, school or ability to care for their other children.12 These sorts of fears have been substantiated by recent research from the University of California, San Francisco. For example, researchers found that women denied an abortion (because they were past the facility’s gestational limit for the procedure) were more likely than those who obtained an abortion to be unemployed, receiving public assistance and living below the federal poverty level for years afterwards—despite having similar economic circumstances a year before seeking the abortion.13

The idea of separately sold abortion "riders" is unfeasible and deceptive. In many of their proposals to restrict private insurance coverage of abortion, antiabortion policymakers and advocates have put forward the idea—sometimes through specific legislative language and sometimes only implied—that enrollees would still be able to use their own money to purchase separate insurance policies ("riders") that only cover abortion. They claim this option would mitigate any harm to enrollees’ rights and health.

That idea is unworkable and unreasonable, both in theory and in practice. In essence, it would require that people prepay for an abortion. Yet abortion is a health care service that few people anticipate needing; for example, people do not anticipate an unwanted pregnancy or a severe pregnancy complication. In addition, a requirement that abortion coverage can be offered solely through a rider sends a signal—an intentional one—that abortion is not "real" health care.

In practice, the pre-ACA history of maternity care riders offers a clear lesson that riders do not work. They were rarely offered, and exceedingly expensive when available, because insurance companies assumed that anyone buying coverage for a single service expected to make use of that coverage in the coming year and that would lead to costs for the insurer.14,15 For abortion, riders have been technically allowed under the law in almost all of the states that otherwise ban abortion coverage, but a 2018 report found that they were "practically nonexistent": They simply did not exist in the individual insurance market in those states, and were available for small businesses from just a single insurance company in a single state.16

Conservatives’ arguments about taxpayer rights and indirect subsidies are unworkable and hypocritical. Antiabortion conservatives are also dishonest in making their core arguments for coverage restrictions. An abortion coverage restriction is not some sort of religious exemption for antiabortion taxpayers. Rather, it gives those taxpayers a veto power over insurance coverage that other people can receive. And if the idea of a taxpayer’s veto took root, it would make governing impossible. Antiwar taxpayers would be able to veto funding for the U.S. military. Corporate taxpayers would be able to veto policies that give advantages to their competitors. Anti-tax activists would be able to veto taxes entirely.

Similarly, the argument that spending government money "frees up" private dollars to be used elsewhere (a concept referred to as "fungibility") is one that only ever seems to be applied to reproductive health care.17 The U.S. government has a long tradition of involving private-sector organizations in achieving its goals in areas like public health, social welfare and global development, and fungibility is rarely, if ever, raised as a problem. For example, many billions of federal and state dollars go to religious organizations and charities every year, and by the logic of fungibility, all of that money would free up private funding to proselytize or engage in other religious activities. If that were true, then any government funding to a religious organization would be a violation of the U.S. Constitution’s Establishment Clause, since it would indirectly subsidize religion.

Antiabortion politics threaten progress on expanding and improving health insurance coverage overall. Despite occasional protests to the contrary, few conservative policymakers have demonstrated serious interest in expanding health insurance coverage or taking steps to make it more affordable for everyone. It is obvious that many policymakers only care now because they fear the political consequences of rising premiums and fewer coverage options under their watch. In that context, it should be equally obvious that conservative policymakers’ attempts to impose new abortion coverage restrictions in any proposal to make broader insurance coverage more affordable is an example of bad-faith negotiation. An abortion coverage restriction is a "poison pill," designed to shift the blame to others for conservatives’ failure to compromise and to act constructively. And if conservative policymakers ever waver, antiabortion advocates will force them to toe the ideological line, because advocates see the ongoing fight over health insurance affordability as an opportunity to advance their long-term goal of eliminating abortion coverage.

The consequences of this standoff for the United States are severe: It means that abortion politics will perpetually interfere with any proposal in Congress to expand health insurance options, reduce insurance premiums and deductibles, or do anything else that involves spending federal dollars to make private insurance coverage work better. Similarly, antiabortion conservatives will make abortion coverage a front-line obstacle to more ambitious proposals, such as a "public option" for people in any income bracket to buy into Medicare or Medicaid, or a plan to set up single-payer insurance coverage.

Policymakers and advocates working to make health coverage better for more people in the United States cannot allow antiabortion forces—who will never accept compromise—to get in the way of progress. At the same time, policymakers and advocates must continue to press for repeal of the Hyde Amendment and other abortion coverage restrictions, and work toward requiring that all public and private insurance plans cover abortion—like any other vital health care service—so that it is affordable and accessible for everyone who needs it.