What constitutes taxpayer funding of abortion? This question has been the common thread in recent and high-profile policy battles, ranging from passage and implementation of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) to attempts to defund Planned Parenthood. Direct federal funding of abortion care has been banned since the mid-1970s in all but the most extreme cases, both domestically and in U.S. foreign aid programs. Regardless, the question continues to arise, in large part because of reproductive rights opponents’ long-standing reliance on the argument that "money is fungible," which they use to attack access to not just abortion, but family planning and other health care services as well.

"Fungibility" is the presumed interchangeability of government and private funds. As applied to abortion, the argument goes that taxpayer funding should not go to organizations that use their own funds to perform abortions (or related work, such as abortion counseling, referral or advocacy), because doing so frees up other resources, which amounts to indirect government support for abortion. It is premised on the notion that once an organization accepts even a small amount of government money for a discrete purpose, the government may dictate how that organization spends its private money as well. Promoted by abortion opponents for four decades, the fungibility argument is central to several long-standing strategic goals of those opposed to abortion and reproductive rights more generally: to make abortion care less accessible; to stigmatize abortion and isolate it from other health services; and to use opposition to abortion as a cover to weaken reproductive health services and providers more broadly.

From Funding to Fungibility

One of abortion rights foes’ earliest—and arguably most successful—strategies has been to prohibit government funding of abortion. The 1973 Helms Amendment bans the use of U.S. foreign assistance to pay for abortion "as a method of family planning."1 Its domestic counterpart, the Hyde Amendment, followed in 1976 and constitutes a near-total ban on using federal funds to pay for abortion care for low-income women insured through the joint federal-state Medicaid program. In fiscal year 2010, the last year for which such data are available, the federal government funded only 331 out of over 1.1 million U.S. abortions.2,3 However, while federal Medicaid dollars cannot be used to pay for most abortions, states may cover the procedure for Medicaid enrollees using their own funds, as 15 states do currently.4

Building on the Hyde and Helms Amendments, abortion opponents have used fungibility primarily as a cudgel against organizations—both internationally and domestically—that receive U.S. funds to provide contraceptive services, but use other funds to provide abortions or abortion-related counseling, referrals or advocacy.

Federal Restrictions

The fungibility argument has long been the justification for attacks against the U.S. overseas program for family planning and reproductive health (see table). This strategy has manifested itself in two key ways. The first is the global gag rule, also known as the Mexico City policy, which was first imposed by President Reagan in 1984 and prohibited U.S. international family planning aid from going to foreign nongovernmental organizations that used their own, non-U.S. funds for abortion services or advocacy (see "The Global Gag Rule and Fights over Funding UNFPA: The Issues That Won’t Go Away," Spring 2015).5 When implemented, the global gag rule hampered some of the developing world’s most effective family planning programs. The second strategy is blocking U.S. funding for the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), based on the allegation that the organization indirectly supports coercive abortions in China, despite U.S. government findings clearing it of any involvement in such practices. Both these restrictions have become political footballs and have been imposed or eliminated depending on the political party of the U.S. president.5 Neither policy is currently in place.

In the domestic sphere, too, fungibility-based attacks on family planning providers and programs have been a mainstay of antiabortion and anticontraception activists’ playbook for decades.6,7 Many of these attacks have focused on the Title X program, the lynchpin of the national system of safety-net family planning providers. In 1988, the Reagan administration issued regulations that came to be known as the "domestic gag rule." These regulations prohibited Title X–funded projects, which were already barred from paying for abortions, from engaging in nondirective counseling and referral for abortion, even when specifically requested by the woman. In addition, the regulations required the physical and financial separation of Title X projects from any program providing abortion or information about the procedure, and barred Title X–supported providers from advocating for or otherwise promoting abortion. All this resulted in lengthy legal and political battles—including a U.S. Supreme Court decision and legislative override attempts by Congress—that ended only when President Clinton suspended the regulations upon taking office in January 1993.

In 2000, the Clinton administration issued final rules that confirmed the right and obligation of Title X providers to provide pregnant women with nondirective counseling about all legal medical options and with referrals for services, including abortion, upon request. These rules also clarified that Title X–supported activities must be separate and distinct from any non–Title X abortion services to comply with the law’s prohibition on use of Title X funds for abortion.8

The Clinton administration’s regulations did not end the attacks on Title X at the federal level. In 2001, Rep. David Vitter (R-LA) sought to attach an amendment to pending appropriations legislation that would have denied Title X family planning dollars to otherwise-qualified, community-based nonprofit agencies that use non–Title X funds to perform abortions. Variations of this amendment have resurfaced regularly since that time, albeit unsuccessfully.

State-Level Restrictions

The fungibility strategy has also been used for decades by state policymakers, who have often been the ones to design and test new approaches to restrict the use of family planning funds. As far back as 1978, Minnesota attempted to defund the statewide Planned Parenthood affiliate by making it ineligible to receive state family planning funds because of its abortion-related activities. This law—as well as similar ones in Illinois and North Dakota in 1979, and Arizona in 1980—was struck down by the courts.9

Another wave of attempts by various states to restrict family planning funding came in the late 1990s. Missouri stands out for aggressively attempting to defund entities affiliated with the provision of abortion care, including by prohibiting abortion referral and by banning providers who perform abortions from receiving state family planning funds, among other restrictions. These actions resulted in multiple court cases that struck down successive attempts to restrict the state’s family planning funds. Ultimately, the Missouri legislature gave up on trying to satisfy the courts and deleted the family planning line item from its budget in 2003.7

Another fungibility-based line of attack emerged in the 2000s, when some states began imposing more tailored abortion-related restrictions on state family planning funds. For instance, Ohio put in place a tiered priority system for the distribution of family planning funds—including federal funds distributed by a state agency—that funnels money to health departments first, leaving little if any money for family planning centers associated with the provision of abortion services.10

Pressing the Argument

Fungibility-based attacks have continued unabated in recent years. For instance, at the federal level, the Republican-led House and Senate have tried to reimpose the global gag rule (which was rescinded by President Obama soon after he took office in 2009) and to prohibit U.S. funds from going to UNFPA. These efforts have remained unsuccessful.11

On the domestic side, having failed to deny family planning funds to organizations that offer abortions, foes of abortion rights—many of whom also oppose some or all forms of contraception12—have tried to eliminate Title X as a whole under the guise of countering abortion and defunding Planned Parenthood. In 2011, the U.S. House of Representatives voted for the first time to defund the program entirely,13 a line of attack that has since been repeated in various congressional votes. Meanwhile, the federal-level effort to defund Planned Parenthood reached its high water mark in 2015 when, following the release of a series of deceptively edited videos in mid-2015, both chambers of Congress voted to block all federal funding—including Medicaid reimbursement—for the organization and its affiliates for at least one year. This legislation was vetoed by President Obama in early 2016.

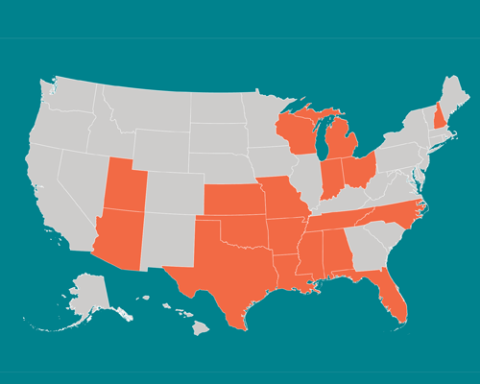

In the states, too, fungibility-centered attacks on family planning providers and programs have continued, with 18 states adopting new restrictions since January 2011 (see map). One wave of such efforts came in 2011–2013 in Arizona, Indiana, Kansas, North Carolina and Oklahoma. Many of these attacks were along familiar lines, such as enacting priority systems for distributing family planning funds or making providers affiliated with abortion care ineligible for such funds. New regulations proposed by the Obama administration in September 2016, once finalized, could head off this type of discrimination in the Title X program by preventing Title X grantees, most notably state health departments, from denying funding to qualified family planning providers merely because they also provide abortions or related care.

Undermining Medicaid

During this period, a strategy to cut Planned Parenthood and other abortion providers out of Medicaid started to gain significant traction at the state level as well. One state at the forefront of attempting to cut off Medicaid funding has been Texas, which in 2011 moved to ban any health center from participating in its Medicaid family planning expansion program if the center provided abortion or was associated with a provider that did so. This decision violated federal Medicaid law prohibiting discrimination against qualified providers and resulted in Texas forgoing federal financial support by reconstituting the program as an entirely state-funded effort. The state’s decision to press ahead roiled family planning services and, by 2013, resulted in a sharp reduction in the number of women receiving contraceptive care.14

Undeterred by the likelihood of running afoul of legal protections embedded in Medicaid, states have continued to press this line of attack, with the effort kicking into overdrive following the summer 2015 release of the videos designed to discredit Planned Parenthood. Between July 2015 and July 2016, 24 states attempted to restrict eligibility for family planning and related funds, of which 17 moved to limit family planning providers’ eligibility for reimbursement under Medicaid.15 Where adopted, most of these efforts have been blocked through legal challenges, including almost all of the attempts to restrict Medicaid. In fact, the flurry of efforts to cut off Medicaid eligibility for family planning providers who have ties to abortion prompted the federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services to issue a strong reminder in April 2016 that such actions violate federal law.16

Pursuing Planned Parenthood

Stretching the argument even further, conservatives’ campaign against abortion access in general and Planned Parenthood in particular has given rise to a veritable cottage industry of fungibility-based efforts to impede Planned Parenthood’s public funding. One such strategy has been to make Planned Parenthood ineligible not just for family planning funding, but for other public health funding streams as well. This has included funding for screening for HIV and other STIs, breast and cervical cancer, and other health conditions, as well as for the provision of sexuality education. Between July 2015 and July 2016 alone, 10 states attempted to implement such restrictions.16

Other examples abound: In Missouri, State Senator Kurt Schaefer made headlines in 2015 with his attempt to block the dissertation of a doctoral student at the University of Missouri, a school that receives state funding, who is seeking to evaluate the impact of the state’s 72-hour abortion waiting period. Schaefer, chairman of the state senate’s interim Committee on the Sanctity of Life, cited the state’s ban on public funding for abortion and argued the dissertation is "a marketing aid for Planned Parenthood—one that is funded, in part or in whole, by taxpayer dollars."17 At the time, the doctoral student was employed as a research coordinator at the local Planned Parenthood affiliate; according to the university, she did not receive any scholarships or grants from the school for her research project.

Another fungibility-inspired avenue of attack has been to target public- and private-sector employees’ charitable gifts that are made through employer-based donation or automatic matching programs. In the early 1980s, the head of the U.S. Office of Personnel Management—an outspoken abortion rights opponent—attempted to exclude Planned Parenthood from the Combined Federal Campaign, under which federal employees can make charitable gifts to qualifying organizations; the effort was ultimately blocked in court.18 More recently, but along similar lines, Arizona in 2015 successfully excluded the local Planned Parenthood affiliate from the State Employee Charitable Campaign, under which state workers can give to local nonprofits through payroll deductions or one-time donations;19 Planned Parenthood had participated in the program for 30 years, but was excluded by state officials on the grounds that it "is not the best fit with the mission or standards of the campaign."

Related arguments were advanced at the federal level during congressional reauthorization of the Export-Import Bank. Antichoice activists argued that corporations like Boeing—which matches employees’ donations to a range of charitable organizations, including Planned Parenthood—should be ineligible to receive export subsidies because these public funds could end up supporting Planned Parenthood.20 Citing this concern, Rep. Mick Mulvaney (R-SC) introduced an amendment that "prohibits Export-Import Bank assistance involving companies that fund Planned Parenthood directly or through third-party organizations";21 the amendment was later withdrawn.

Even broader arguments have been advanced in an attempt to assert that taxpayer funding of abortion in general and of Planned Parenthood in particular is rampant in the United States, including via the tax-exempt status of employer-sponsored health plans that cover abortion and the nonprofit tax exemption of Planned Parenthood that makes any private donation to the organization tax deductible.22

Affordable Care Act

The concept of fungibility has also been deployed to undercut private insurance coverage of abortion. One high-profile example is the debate over and passage of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) in 2009 and 2010. Abortion quickly became central to the debate, not the least because opponents of the ACA seized on the fungibility-based argument that any public subsidies for insurance plans that cover abortion amounts to taxpayer funding for abortion.

While the ACA was ultimately signed into law, it came at the price of the Nelson Amendment, a convoluted provision intended to appease antiabortion lawmakers by preventing comingling of public and private monies in any plans in the ACA’s health insurance marketplaces that cover abortion (see "Insurance Coverage of Abortion: The Battle to Date and the Battle to Come," Fall 2010). Related battles have raged on. For example, in May 2011, the House passed the No Taxpayer Funding for Abortion Act, which could have eliminated abortion from both private and public insurance coverage. Most notably, the bill would have effectively forced abortion coverage out of the ACA’s marketplaces by prohibiting a plan from covering abortion if even one individual enrolled in the plan received any federal insurance subsidies. This scheme would have had essentially the same impact as the Stupak Amendment, an antiabortion proposal that Congress rejected during the original debate on health reform. Moreover, the bill would have prevented the use of tax-exempt Health Savings Accounts and Flexible Spending Accounts to pay for abortion care.

While this and other legislation to eliminate abortion coverage from the ACA’s marketplaces have stalled at the federal level, abortion foes have successfully promoted similar measures in the states. As of October 2016, 25 states ban abortion coverage in plans offered through the ACA’s insurance marketplaces, with varying exceptions for cases involving life endangerment, rape and incest.23 In addition, opponents of abortion rights have attempted to ban abortion coverage in so-called multistate plans, which were established under the ACA to generate additional insurance options for consumers. They argued that because the federal government negotiates directly with insurers to establish these plans, that negotiation would amount to indirect support for abortion if abortion were covered. (The ACA already includes a requirement that at least one multistate plan offered in each state must exclude abortion coverage.)

Flawed Argument, but Real Harm

The antiabortion movement’s reliance on the concept of fungibility to undermine access to publicly supported reproductive health services is conceptually flawed, deeply hypocritical and shows irresponsible disregard for the vulnerable groups of women in need of these services.

On one level, the argument that providing family planning funding to organizations frees up any significant funding to subsidize abortion does not hold water, if only because publicly supported family planning services and providers are already underfunded. For example, Congress has cut funding for Title X by 10% since 2010, even as the need for publicly funded contraceptive services and supplies increased by 5% over the same period.24 In fact, taking inflation into account, funding for Title X is roughly 70% lower today than it was in 1980.25 Further, Medicaid reimbursement for family planning services provided by Title X clinics typically covers less than half of the actual cost of rendering these services.26

Additionally, state and federal government policies that consciously drive a wedge between providers of publicly supported contraceptive services and facilities providing abortions are self-defeating tactics for abortion opponents, since they can make it more difficult for a woman obtaining an abortion to get the postabortion contraceptive care she may need to prevent another unintended pregnancy and the abortion that might follow.27,28

On a more basic level, however, there are several flaws in the fungibility argument. For one thing, there is a longtime American tradition of involving private-sector organizations in achieving the U.S. government’s goals in areas like public health, social welfare and global development. Fungibility is an inherent possibility when involving the private sector in any government-subsidized activity, and the only way to avoid it would be for government agencies to exclusively provide any and all such services.

Further, it is hypocritical to suggest that fungibility is only a problem where family planning and abortion providers are concerned, but not for myriad other government-subsidized activities, including the billions in U.S. taxpayer dollars that go to religious organizations and charities. By the logic of fungibility, any government aid to faith-based charities inevitably frees up these organizations’ private funds to proselytize or engage in other religious activities. For instance, the U.S. government awards hundreds of millions of dollars annually to groups like Catholic Relief Services and Catholic Charities that are controlled by or otherwise affiliated with the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops,29,30 which is often among the most vocal voices invoking fungibility-based arguments to attack reproductive health programs and providers.31 If public funding for contraceptive services indirectly subsidizes abortion, then public funds going to organizations controlled by or affiliated with the Catholic hierarchy inevitably subsidize its inherently religious activities. Notably, government funding for religious activities is prohibited under the U.S. Constitution’s Establishment Clause.

But the most troubling aspect of the fungibility strategy is that, ultimately, it targets not only family planning providers and programs, but the millions of women who rely on them to obtain essential health care. The Hyde and Helms Amendments are aimed squarely at the most vulnerable women: those who are poor or otherwise disadvantaged and therefore struggle to access abortion care. Fungibility-based attacks are an extension of these harmful policies and likewise target vulnerable women—whether it is by shuttering successful programs in developing countries, by trying to dictate that women enrolled in Medicaid cannot obtain contraceptive services from the provider of their choice or by explicitly targeting safety-net family planning centers supported by Title X. Whether the harmful impact of these attacks is by design or just accepted as collateral damage in the abortion wars, it shows alarming disregard for the real-life effect on millions of women and couples.

The fungibility strategy started with banning direct abortion funding and is likely to continue as long as the notion that government should not pay for abortion prevails. Reproductive health, rights and justice advocates have always maintained that to protect the health and redeem the full human rights of women in the United States and overseas, all restrictions on U.S. abortion funding and insurance coverage must be repealed. Toward that end, there have been renewed efforts in recent years—from grassroots and digital organizing to legislation introduced in Congress—to repeal the Hyde Amendment and, at the very least, to soften the harmful impact of Helms (see "Abortion in the Lives of Women Struggling Financially: Why Insurance Coverage Matters," 2016 and "Abortion Restrictions in U.S. Foreign Aid: The History and Harms of the Helms Amendment," Summer 2013).

Ultimately, repealing all abortion coverage bans and restrictions is not only good policy in its own right, it is also the surest way to put an end to fungibility as a pretext for attacking family planning providers and programs.