Updated on June 29, 2020:

On June 29, 2020, the U.S. Supreme Court struck down Louisiana’s harmful admitting privileges requirement in June Medical Services v. Russo. The Court’s 5-4 decision prevented the restriction from going into effect, allowing the state’s three remaining clinics to stay open. The Court also rejected Louisiana’s argument that abortion providers do not have standing to challenge abortion restrictions on behalf of their clients.

First published May 11, 2020:

The U.S. Supreme Court heard oral arguments in June Medical Services v. Russo in March 2020 and its forthcoming decision in that case could have profound implications for abortion rights and access in Louisiana and other states.

The lawsuit is a challenge to a Louisiana law that requires abortion providers to have admitting privileges at a local hospital. In 2016, the Court struck down an identical restriction imposed by Texas, ruling that admitting privileges requirements are unconstitutional because they shut down abortion clinics without providing any health or safety benefits to patients. If the increasingly conservative Supreme Court uses the current case to walk back its own precedent, abortion services in Louisiana could be drastically reduced for almost one million women of reproductive age across the state.

States Poised to Take Action

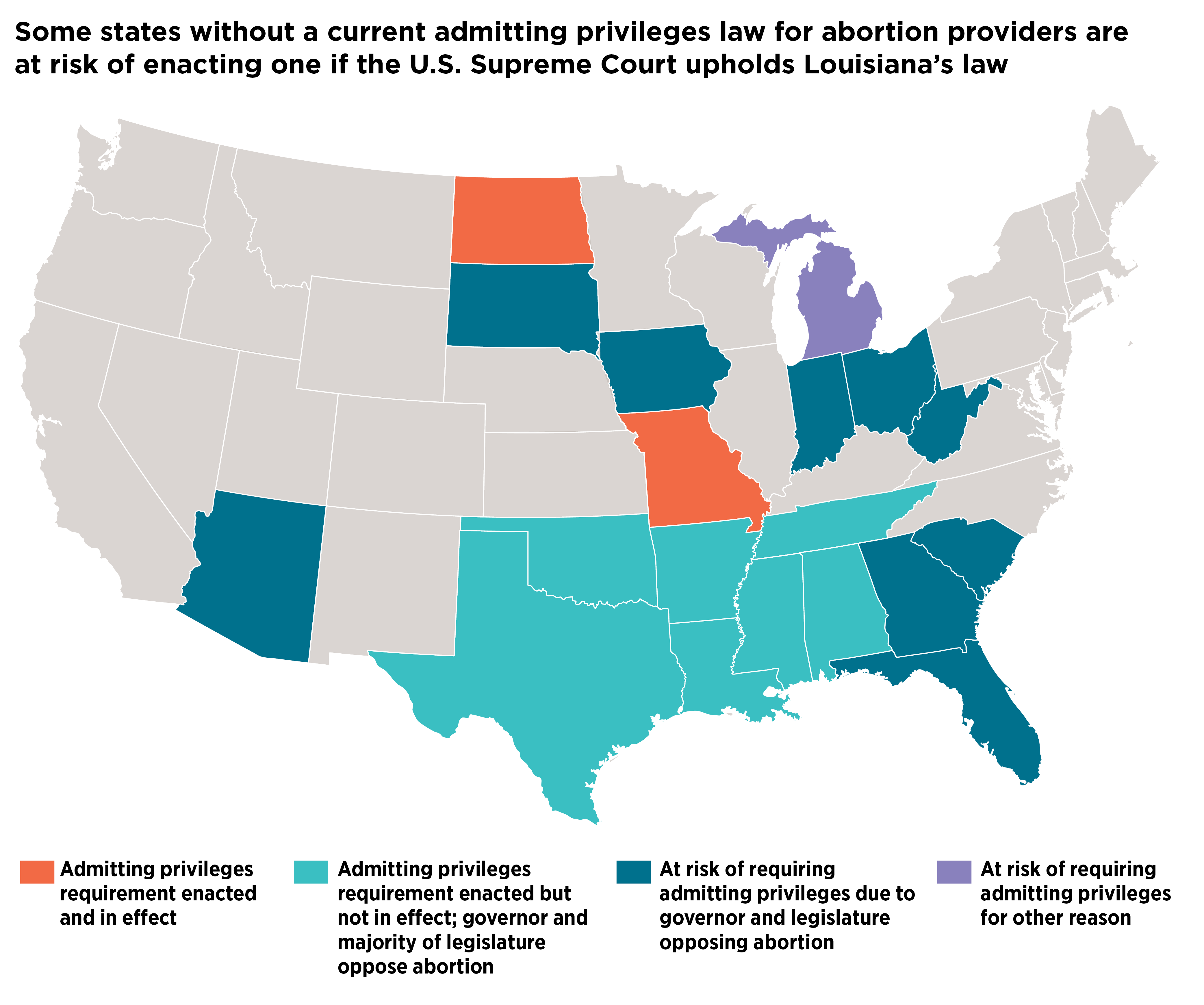

A decision allowing Louisiana’s law to go into effect would embolden antiabortion lawmakers in other states to impose additional, draconian restrictions on abortion care. History demonstrates that opponents of abortion, perceiving an invitation from the Supreme Court, would not limit themselves to just one type of restrictive policy. However, in the wake of the Louisiana case, one obvious option for states without active admitting privileges requirements would be to move swiftly to impose this type of restriction on providers, further tightening the web of antiabortion policies that limit access to care.

The most direct way for a state to add this type of restriction to its active policies would be to adopt new requirements through legislation or regulation. Beyond Louisiana and Texas, there are 15 states in a position to try this because, aside from Michigan, they each have an antiabortion governor and majority of state legislators. Michigan is included in this category even though the current governor supports abortion rights, because the state has a citizen-initiated process by which a law can be enacted without the governor’s approval, and this process has been employed in the past to adopt other abortion restrictions. Almost all of these 15 states are in the South, Midwest and Plains.

This group of states includes five that already have admitting privileges requirements on the books—laws that are not currently in effect due to litigation, but which could potentially be used to achieve the same end, if states are able to revive the requirements through court action instead of by legislative or administrative processes. Among these five states, only Tennessee’s law was ever in effect. Two additional states—Kansas and Wisconsin—have passed admitting privileges laws that have also been blocked by courts, but because of subsequent political changes, these states are less likely than the other 15 to seek to have their restrictions enforced. Both states now have elected leadership that supports abortion rights.

Potential Impact on the Clinic Landscape

Admitting privileges requirements are among a class of abortion restrictions known as TRAP (targeted regulation of abortion providers) laws that have been clearly tied to clinic closures over the past decade. The effect that an admitting privileges requirement can have on the abortion clinic landscape is not theoretical or abstract—it has been well documented, particularly in Texas, where the requirement was in effect from November 2013 to June 2016. During that time, the abortion clinic network in the state was cut by half, with the number of clinics dropping from 41 to 22. The remaining clinics were concentrated in urban areas, leaving vast regions of the state without abortion care. Based in part on this negative impact on access to abortion services, the Supreme Court struck down the admitting privileges requirement and other clinic regulations in 2016. However, the effects are not easily reversible: The number of clinics in Texas has not rebounded to pre-2013 levels (in 2017, there were 21 clinics statewide).

For other states where admitting privileges requirements have been challenged in the past, court filings by clinics clearly demonstrate the potential impact of these harmful restrictions:

- In Tennessee, the admitting privileges requirement was in effect from July 2012 to April 2017. During that time, two clinics closed (in Knoxville and Memphis) and the remaining seven clinics’ capacity was reduced as existing providers were not able to obtain privileges and clinics had difficulties recruiting new providers. When the requirement was in effect, patients faced delays of two or three weeks to obtain an abortion.

- Mississippi has only one abortion clinic, and the legal filing in that case documents the steps the clinic took to try to obtain admitting privileges without success before the law was blocked by the court. At least one hospital refused to even provide an application to the provider despite repeated attempts and another hospital would not review a completed application.

- In an order blocking enforcement of Alabama’s law in 2014, the court determined that none of the providers in Birmingham, Mobile or Montgomery would be able to obtain privileges and no physician with privileges would start providing abortion care. This would leave only two abortion clinics open in the state, in Huntsville and Tuscaloosa.

Had these states been successful in requiring admitting privileges, access to abortion for patients in those states would be even more limited than it is today. Moreover, it is important to understand how these effects can play out across state lines, contributing to even larger changes in abortion access around the country. For example, if neighboring states adopt similar measures, patients in entire regions of the country may be forced either to travel long distances to obtain abortion services or be left without access to care. At the same time, clinics in states without admitting privileges requirements must figure out how to care for an influx of patients who manage to travel from states with clinic closures.

Abortion care is already quite limited in the 15 states that may pursue admitting privileges requirements following the Supreme Court’s decision in the Louisiana case, with most having only a handful of abortion clinics and long driving distances already. For all but three of these states, the rate of abortion clinics per million women aged 15–44 ranges from 1.7 to 7.0. And patients tend to have long driving distances to reach a clinic, with average one-way drives between 23 and 92 miles in 10 of these states. (In comparison, in all but two of the 15 states that are supportive of abortion rights, the rate of clinics per million women of reproductive age ranges from 15.0 to 69.3, and the one-way driving distance to reach a clinic in 10 of these states is less than 10 miles.)

Abortion clinics will be directly targeted by any additional admitting privileges requirements, which will have potentially devastating effects on abortion access across a wide swath of the country. Of course, this is the result desired by proponents of admitting privileges restrictions. The question that remains to be answered is whether the Supreme Court will follow precedent or follow politics.