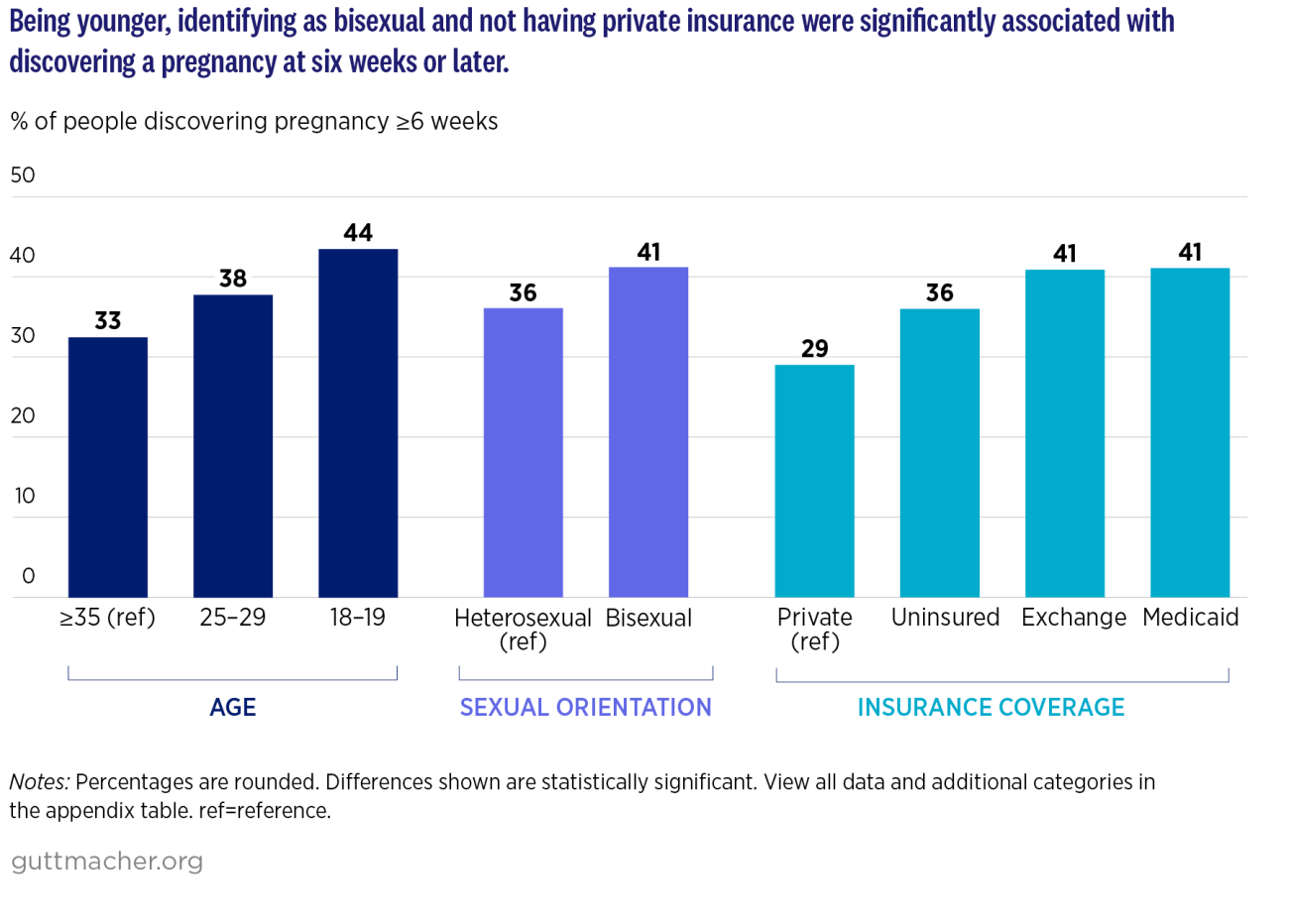

Because those who have fewer resources and more challenges accessing health care are also more likely to find out about their pregnancies after, rather than prior to, six weeks, banning abortion early in gestation reinforces existing inequities in access to care. These bans compound obstacles and make navigating systemic barriers to abortion even more difficult for individuals.

Youth

Adolescents often have less information than adults about sexuality, pregnancy prevention and how to access reproductive health care, in part because of the lack of comprehensive and medically accurate sex education in the United States. In addition, research shows that adolescents are more likely than adults to rely on others for transportation for abortion care and to have difficulty paying for care.

Discriminatory policies exacerbate these obstacles further for minors. Thirty-six states have parental notification and/or consent policies, which can delay care and can force young people to involve family members in their abortion-seeking even when it is not safe to do so. Although this analysis finds that 18- and 19-year-olds—who would not be subject to these laws—are more likely than older adults to discover their pregnancies later, parental involvement laws contribute to a hostile environment for all young people to get care and increase abortion stigma.

People with limited financial resources

Insurance coverage of abortion in the United States is highly restricted, with inequitable and discriminatory policies at the state and federal levels. The Hyde Amendment and other similar policies prohibit federal funding—including federal Medicaid dollars, Medicare and other government insurance and health care programs—from covering abortion care, except in cases of life endangerment, rape or incest. Meanwhile, 32 states and Washington, DC, currently place the same restrictions on, and follow the same standard on exceptions for, state Medicaid funds.

These policy restrictions block hundreds of thousands of people from using their public insurance for abortion. As a result, most abortion patients are forced to pay for their care out of pocket, an expense that pregnant people with fewer financial resources may struggle to afford. These restrictions are especially harmful for communities of color. The long legacy of racism in the United States has led to disproportionate rates of Black, American Indian and Alaska Native, Hispanic, and Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander people qualifying for public insurance and thus being disproportionately impacted by coverage bans. In addition to the cost of care itself, a range of ancillary costs—such as transportation, lodging, lost wages from time off work and child care—can push abortion further out of reach.

LGBTQ+ individuals

Abortion seekers who identify as LGBTQ+ face unique barriers to care. LGBTQ+ individuals are more likely than others to face discrimination from health care providers and systems, to receive inadequate sex education and to lack insurance. Further, the absence of inclusive sexual and reproductive health services may deter these individuals from seeking abortion care altogether.

Early pregnancy recognition does not guarantee timely abortion care

Delayed pregnancy recognition can make getting an abortion more difficult at any point during pregnancy and has long been a factor for individuals needing care later in pregnancy. Laws that ban abortion at early gestational durations make timing of pregnancy discovery consequential for even more pregnant people.

Our analysis found that less than a quarter (24%) of people who knew that they were pregnant before six weeks were also able to obtain an abortion before six weeks. That proportion increases to only half (53%) when including those who were able to access care during the sixth week of pregnancy. Although most respondents found out they were pregnant before six weeks, three-quarters did not receive abortion care before that time.

In the context of six-week bans, this finding is troubling. After recognizing their pregnancy, people considering abortion must also make their decision, find a provider, get funding and schedule an appointment before the six-week limit.

States banning abortion early in a pregnancy have other restrictions, all of which make it difficult to access timely care. For instance, all four states with six-week bans currently in effect also have mandatory and medically unnecessary 24-hour waiting periods and restrictions on public insurance coverage of abortion. These bans are part of the restrictive and continually shifting landscape of abortion laws post-Dobbs.

In states with six-week bans, the third of people who do not discover they are pregnant before six weeks may be forced to arrange out-of-state travel to obtain abortion care, which is only possible if they have sufficient resources or can receive adequate assistance from abortion funds or practical support networks. Because the states with six-week bans are in the South and Midwest, where states implementing total or restrictive bans are concentrated, many people must cross multiple state lines and travel hundreds of miles to get in-clinic care.

With 13 states banning abortion entirely, there are also increasing constraints for providers. The number of brick-and-mortar clinics has decreased since Dobbs, and many clinics in states without abortion bans have taken on substantially more out-of-state patients, especially in states that border those with bans. Increased patient volumes limit clinic capacity, appointment availability and patient access. These provider-side impediments compound patient obstacles to make abortion care more challenging to access, particularly for people who recognize their pregnancies at or after six weeks.

Under the protection of certain abortion shield laws, which have been enacted by a number of states after Dobbs, health care providers can offer medication abortion via telehealth to out-of-state residents, including those living where abortion is fully or partially banned. Still, this relatively new approach to abortion provision may not be known to—or preferred by—some people needing an abortion. Certain abortion seekers may need to access procedural care. Others may self-source alternative methods of abortion care, such as medication abortion obtained from a community group, either because it is their preference to do so or because they are unable to access clinician-provided care. Individuals who lack any of these options may be forced to remain pregnant.

Two years out from Dobbs, we are just beginning to understand the full harm of six-week bans. Recent reporting brought to light the tragic—and preventable—deaths of Amber Thurman and Candi Miller, who were unable to access abortion care in Georgia while the state’s six-week ban was in effect. These cases, while among the first documented, will certainly not be the last to demonstrate the devastating, fatal consequences of banning abortion based on early gestational duration.

Conclusion

Abortion bans at any gestation are unacceptable. These arbitrary limits on abortion access impinge on individuals’ reproductive autonomy and worsen existing inequities. Bans at six weeks’ gestation make it particularly difficult for people to receive abortion care, in part because almost four in 10 people will not discover their pregnancy that early. Even then, knowing that they are pregnant far from guarantees that people can get an abortion by the six-week cutoff.

The imposition of six-week bans within a landscape in which 13 states have enacted total abortion bans compounds the harm of these restrictions and increases the urgency for policy solutions that mitigate the terrible consequences of Dobbs. These data on who learns that they are pregnant at six weeks or later provide additional evidence that abortion bans impose the most harm on people who already face the greatest obstacles to care.

Methodology

This analysis focuses on responses to the question, “About how many weeks pregnant were you when you found out you were pregnant?” Individuals who did not respond to this question (222) or who responded “don’t know” (102) were excluded from the analyses, as were respondents who indicated that they found out about their pregnancy at a later gestation than when they actually reported obtaining their abortion (51). We also excluded 530 individuals who obtained abortions in Texas after the implementation of Texas Senate Bill 8 in September 2021, which banned abortions at six weeks’ gestation. We excluded these individuals to keep the sample comparable, as all 530 respondents obtained their abortions at or before six weeks/prior to the detection of fetal cardiac activity. The analytic sample consists of 5,793 respondents who obtained care at 54 clinics.

All sociodemographic variables are based on respondents’ self-reports. Respondents from the analytic sample who did not answer the item about sexual orientation (136) were excluded from analyses using this measure. Data for this analysis were weighted.