By July 1, legislators in all but six states and the District of Columbia had completed their work for the year. Issues related to sexual and reproductive health and rights continued to be hot topics in capitals across the country during the legislative sessions, including an ongoing surge in proactive measures, primarily around contraceptive access.

However, the June 27 retirement of Justice Anthony Kennedy from the U.S. Supreme Court looms large over the state policy landscape, in particular for its potential to reshape abortion access and ongoing abortion litigation. For decades, Kennedy has provided a critical swing vote, including by siding with the majority in the 2016 Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt decision to overturn abortion restrictions in Texas. Kennedy’s replacement could tip the balance on the Court in critical ways, potentially giving states increased latitude to restrict abortion and putting the fundamental holding of Roe v. Wade in jeopardy.

Courts continue to play a pivotal role in shaping reproductive health and rights policy. So far this year, courts have blocked implementation of restrictions in seven states that would limit access to abortion services; some of these have been blocked on a temporary basis while litigation and appeals continue. In the first six months of the year, no court has issued a decision in favor of a challenged abortion restriction. Also, litigators unveiled a new strategy this year for challenging abortion restrictions. This new approach focuses on the collective impact of multiple restrictions, rather than on the unique impact of a single restriction. In Indiana, Texas and Virginia, litigators filed cases challenging a constellation of abortion restrictions; courts have yet to rule in any of these cases.

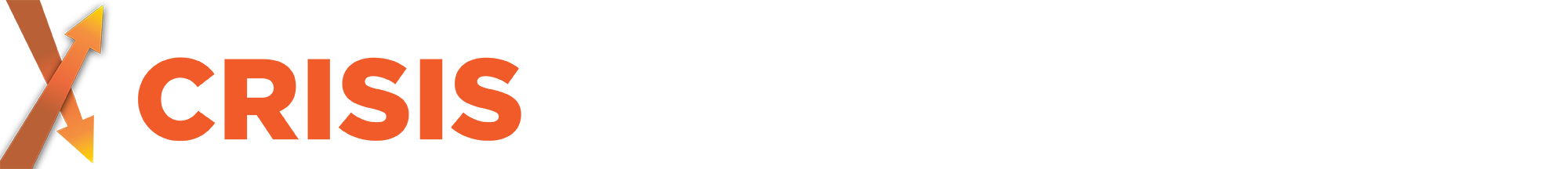

The change in Supreme Court justices is taking place against a backdrop in which 29 states already have enough abortion restrictions in effect to be considered either hostile or extremely hostile to abortion rights;1 four states in the "extremely hostile" category also have so-called "trigger" laws on the books that would immediately ban abortion if Roe were overturned (see map). This year, many state legislators continued their efforts to restrict reproductive rights or access to care. In the first six months of 2018, 11 states enacted 22 new abortion restrictions and four states moved to impose new restrictions on providers that can receive public funds for family planning programs.

Restricting Access to Abortion

During the first half of the year, 11 states adopted 22 new abortion restrictions. In addition, the West Virginia legislature approved a resolution to place an initiative on the November ballot that would roll back abortion protections in the state. If approved by voters, the measure would insert language specifying that the state’s constitution does not secure or protect a right to abortion and does not require public funding of abortion. West Virginia is one of 17 states that currently fund abortion (see State Funding of Abortion Under Medicaid). Voters in Alabama will vote this November on whether to grant personhood at conception; the measure is on the ballot because of a resolution adopted by the state legislature in 2017.

Ban abortion under certain circumstances. Four states adopted measures aimed at banning abortion under some circumstances.

- Iowa enacted a new law that bans abortion as early as six weeks of pregnancy based on the detection of a fetal heartbeat. The law is not in effect because of ongoing litigation. North Dakota is the only other state that has enacted a ban at six weeks; enforcement of that law was struck down by a federal appeals court in 2015 (see Abortion Policy in the Absence of Roe).

- Louisiana and Mississippi banned abortion at 15 weeks after the last menstrual period. Neither of these measures is in effect. A federal district court enjoined enforcement of the Mississippi law in April. In a very unusual move, the Louisiana legislature specified that the ban will only take effect if Mississippi’s law is upheld.

- A new law in Kentucky would ban the primary method of abortion used after 12 weeks of pregnancy. This ban on dilation and evacuation abortion is not in effect because of ongoing litigation. Similar bans are in effect in Mississippi and West Virginia (see Bans on Specific Abortion Methods Used After the First Trimester).

Abortion reporting requirements. Three states expanded their existing abortion reporting requirements to include information on the reason for the abortion, complications resulting from an abortion, or both.

- A new law in Arizona requires information on the specific reason for the abortion, ranging from elective to coercion to domestic violence. It also requires additional information in case of abortion complications.

- Indiana added a requirement that providers report on whether the abortion is being sought because of domestic violence, coercion, harassment or human trafficking. It also requires information on whether a minor obtained parental consent or received a judicial waiver. The law requires reporting on abortion complications, including psychological or emotional complications, adverse reactions to anesthesia, and whether complications arise during a subsequent pregnancy.

- A new law in Idaho requires providers to report on complications following an abortion, including psychological or emotional complications, adverse reaction to anesthesia, complications in subsequent pregnancies or later diagnosis of breast cancer.

When these laws go into effect, 17 states will require reporting on the reasons for an abortion and 28 states will require some reporting on abortion complications (see ).

Restricting Family Planning Funds

Even as states continued to restrict abortion rights and access in the first half of 2018, four states also continued their assault on publicly funded family planning. Three states moved to exclude agencies that provide abortion from eligibility to receive family planning funds.

- A new Tennessee law directs the state to seek permission from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), the federal agency that administers Medicaid, to exclude providers that would use state funds directly or indirectly to promote or support abortion.

- In 2016, Louisiana enacted a law that would have barred abortion providers, and those that contract with abortion providers, from receiving any public funds, including through Medicaid; enforcement of the measure was blocked as a result of litigation. In a move designed to address the court’s objections, Gov. John Bel Edwards signed legislation in May that narrows the law so the exclusion is now specific to abortions providers reimbursed by Medicaid.

- In April, Nebraska adopted legislation on the allocation of federal Title X family planning funds that flow through the state treasury to organizations that consider abortion a method of family planning or that perform, assist, counsel or refer for abortion. The new law permits organizations receiving the funds to provide nondirective counseling on a woman’s pregnancy options.

The fourth state, South Carolina—one of the first states to expand eligibility for family planning services under Medicaid—asked CMS for permission to change the program in ways that would make it difficult for health centers that primarily offer reproductive health services to continue their participation. The state is seeking federal permission to allow it to place a bevy of new requirements on providers, mandating that they are able to provide a broad package of care, including treatment for diabetes, hypertension, heart disease, depression and substance use disorders. And then, in early July, Gov. Henry McMaster directed the state Medicaid agency to exclude abortion providers from the program.

In contrast, restrictions on funding for agencies affiliated with abortion providers eased slightly in Iowa and Ohio during the first half of the year. In 2017, Iowa disbanded a long-standing Medicaid family planning expansion in favor of a state-run program and, in the process, excluded abortion providers from participating. In 2018, the legislature revisited the issue, allowing family planning providers that are part of a private, nonprofit hospital network that also provides abortion services to participate in the state-run family planning program. Other abortion providers, including those affiliated with Planned Parenthood, remain excluded. And in April, a federal appeals court struck down an Ohio law that banned Planned Parenthood affiliates from receiving federal funds that flow through the state government and support a wide range of care, including breast and cervical cancer screening, infertility prevention and abstinence education.

Expanding Access to Reproductive Health and Rights

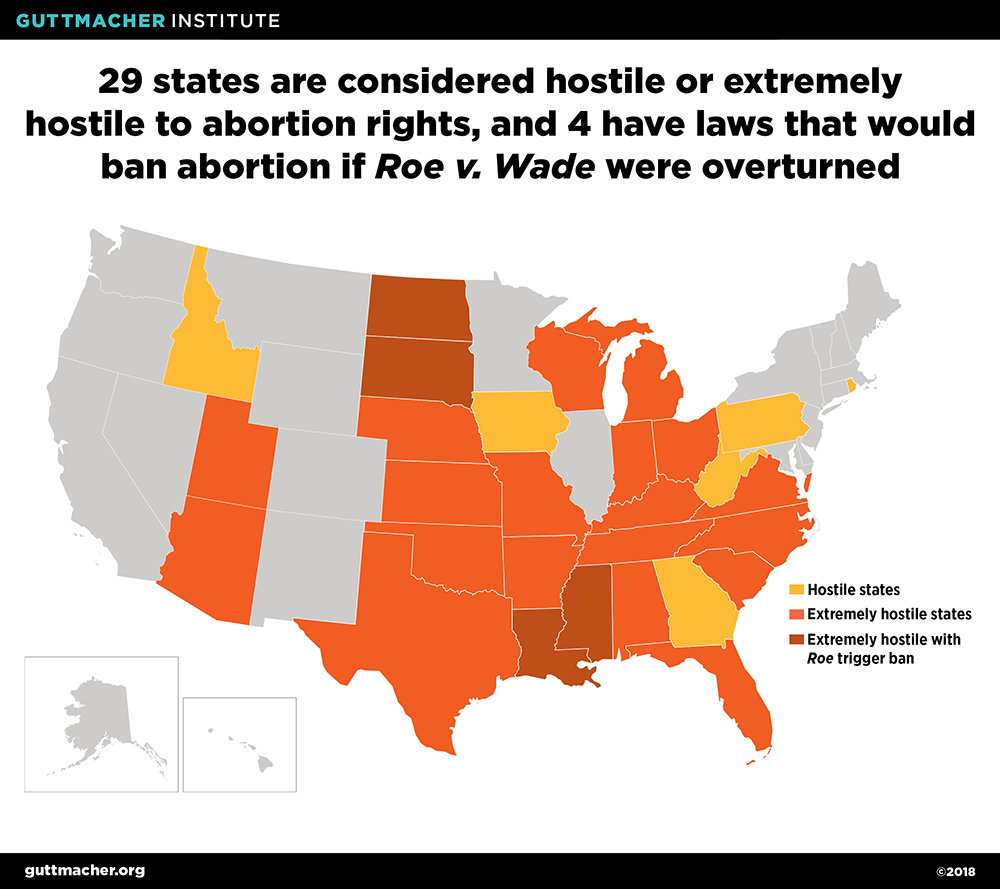

Despite the ongoing onslaught of restrictions in many states, advocates and policymakers continue to make important strides to expand access in some places. Twenty-seven states and DC adopted new measures in the first half of the year to enhance reproductive health or protect reproductive rights.

Abortion. Three states adopted four measures designed to expand abortion access in the first half of 2018. Washington state enacted a measure that will require health insurance plans to cover abortion services if they cover prenatal care (starting in January 2019). The Washington law is similar to measures adopted by New York and Oregon in 2017. Maryland adopted a pair of measures to ensure pregnant incarcerated individuals receive information about abortion providers and transportation to obtain the procedure. Louisiana amended a 2016 law requiring the burial or cremation of all fetal tissue from an abortion so that it now applies only to surgical abortions. The original law, which had not been enforced during ongoing litigation, would have effectively prohibited the use of medication abortion.

Contraception. With opponents of reproductive health and rights looking for opportunities to undermine the federal contraceptive coverage guarantee under the Affordable Care Act (ACA), several states moved to shore up protections for their residents.

- A new law in Washington requires coverage of all contraceptive methods (including over-the-counter methods) approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), contraceptive counseling, follow-up services, and male and female sterilization, all without cost sharing. The law would allow cost sharing for male sterilization procedures if the plan is offered as a health savings account under tax regulations.

- A new law in Connecticut requires health insurance plans to cover a range of essential health benefits, including maternity and newborn care, screenings for STIs, breast-feeding support and supplies, and domestic and interpersonal violence screening and counseling. The law also expands contraceptive coverage under health insurance plans to include—without cost sharing—all FDA-approved contraceptive methods available over the counter, all maintenance and follow-up services, female sterilization and a 12-month supply of hormonal contraceptives at one time.

- DC also enacted a new law that requires health insurance plans to provide coverage for a 12-month supply of a contraceptive method at one time.

- In 2016, Maryland adopted a provision allowing insured individuals to obtain a six-month contraceptive supply at one time; in 2018, the provision was expanded to allow insurance coverage for a 12-month supply.

Including these new laws, 17 states and DC have expanded contraceptive coverage provided under the ACA since the federal requirement became effective in 2013 (see Insurance Coverage of Contraceptives).

In related moves, New Hampshire and Utah both enacted laws that allow a pharmacist to dispense contraceptive pills, patches and rings without a patient first obtaining a prescription. The New Hampshire law applies to anyone seeking those methods, while the Utah law applies only to adults.

Publicly funded family planning services. Three states enacted legislation to direct the state to seek federal permission to expand eligibility for family planning services under Medicaid.

- A new law in New Jersey directs the state to seek permission to provide Medicaid family planning services to individuals with incomes up to 200% of the federal poverty level. (The 2018 federal poverty level is $20,780 for a family of three.)

- A provision adopted in Utah would direct the state to seek federal permission to expand Medicaid family planning services to individuals with an income up to 95% of the federal poverty level; it also requires the state Medicaid program to cover provision and insertion of long-acting reversible contraceptive methods for Medicaid enrollees who have recently given birth.

- A new law in Maryland seeks to increase eligibility for Medicaid-covered family planning services from 200% to 250% of the federal poverty level.

Twenty-two states have already received federal approval to expand Medicaid eligibility for family planning services to individuals based on their income (see Medicaid Family Planning Eligibility Expansions).