The issue of religious and moral exemptions—often referred to as conscience clauses or religious refusals—has reclaimed a central political stage over the past decade, with high-profile disputes over insurance coverage of contraceptives and abortion, same-sex marriage, transgender rights and more. In pressing for expanded refusal rights, social conservatives often put forward the threat of doctors or nurses being required to perform abortions, even though that has been barred by federal law and laws in almost every state since the early 1970s. There are serious harms that can come when doctors, pharmacists or other health care professionals discriminate against the patients they serve or violate legal and ethical standards of care. Therefore, there are strong reasons to limit those refusal rights, and balance them against the rights and needs of patients.

Yet, behind these persistent debates over individual refusal have been long-simmering and in many ways considerably more dangerous attempts to expand refusal rights for institutions. In some cases, social conservatives have worked to expand the scope of laws designed to provide refusal rights to individuals by insisting that owners or CEOs of an institution should be able to refuse on behalf of the entire institution. In other cases, they have used individual refusal rights as political cover for pushing for new refusal policies that expand rights for institutions. Either way, the result is the same: Giving new power to already powerful health care, educational and social services institutions to impose their values and agenda on society.

Social conservatives have fought for extensive religious and moral exemptions for health care, educational, social service and other institutions. Over its eight years, the Obama administration became embroiled with such socially conservative, religiously affiliated institutions as the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops (USCCB) over a series of escalating disputes, including enforcement of the Affordable Care Act’s contraceptive coverage guarantee and recognition of same-sex marriages. Those entities have argued that the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, the federal Religious Freedom Restoration Act and other federal and state laws must be read to exempt them from a wide range of policies (see "Learning from Experience: Where Religious Liberty Meets Reproductive Rights," 2016). The specific demands vary by type of institution, and many date back decades.

Under the Trump administration, religiously affiliated institutions have found a vocal ally for their demands. In May 2017, President Trump issued an executive order on "free speech and religious liberty" that promised a reversal of many Obama-era policies.1 Notably, the administration issued regulations in October 2017 (which are currently enjoined) expanding religious and moral exemptions to the contraceptive coverage guarantee.2 It has backed off of the previous administration’s position that federal antidiscrimination laws protect against discrimination on the basis of gender identity and on the use of reproductive health services.3 And it proposed regulations in January 2018 to interpret and enforce more than 20 federal statutory provisions related to "conscience and religious freedom" in ways that would greatly expand refusal rights for individuals and organizations in the health care field and beyond.4

Conservatives in Congress have also proposed expanded refusal rights: For example, the U.S. House of Representatives has repeatedly passed the Conscience Protection Act, a bill that (if approved by the Senate and signed by the president) would expand on existing federal laws allowing abortion-related refusals, and allow individuals and institutions—including hospitals, insurance companies, social services agencies and employers or schools sponsoring health plans—to sue in federal court for actual or threatened violations of their refusal rights.

Hospitals and health systems. Religiously affiliated hospitals and health systems have traditionally asserted sweeping rights over the type of care patients may receive on-site. For example, Catholic-affiliated hospitals in the United States must abide by the USCCB’s Ethical and Religious Directives for Catholic Health Care Services, which bar providing many types of services, information or referrals related to abortion, contraception, miscarriage management, prenatal diagnosis, infertility and end-of-life care.5 In some cases, the directives’ prohibitions can impede services necessary in emergency circumstances or access to information needed for patients to exercise their right to provide informed consent to their care.6,7

Moreover, these institutions have pushed their restrictions outward in multiple ways. For example, they have insisted that formerly secular hospitals abide by the directives as a condition of a merger.8 They have also forced health care professionals to abide by the directives in their outside activities, such as by preventing hospital employees from moonlighting at an abortion clinic, punishing medical students who pursue training in abortion or preventing doctors with admitting privileges from providing barred services in their private practices.9

Insurance companies and plan sponsors. Religiously affiliated insurance companies, like the New York–based Fidelis, can be major players in their state’s private insurance and Medicaid marketplaces while refusing to cover health care services that violate the Catholic directives, including abortion and almost all forms of contraception. Because those services are mandated under private insurance and Medicaid in New York, Fidelis has worked with a separate company that covers the banned services, but this accommodation has created numerous bureaucratic hurdles for patients and has limited patients’ access to reproductive health providers.10

Insurance plan sponsors, such as employers and universities, have also demanded exemptions from coverage mandates for contraception, abortion, services for transgender patients and other types of care. Most prominently, dozens of nonprofit and for-profit companies objected to the federal contraceptive coverage guarantee and refused to accept any sort of compromise, including the Obama administration’s accommodation. That accommodation allowed an employer or school with religious objections to "step away" from contraceptive coverage—refusing to pay for it, arrange for it or even talk about it—while still ensuring that employees, students and dependents received that coverage directly from the insurance company.2

Pharmacies. Pharmacies and pharmacy chains have repeatedly asserted refusal rights in recent decades, most notably with the advent of emergency contraceptive pills in the 1990s. These businesses have asserted the right to refuse to stock and dispense drugs to which they have religious or moral objections. In some cases, pharmacies have refused to transfer the prescription to another pharmacy or return it to the customer so she could take it elsewhere, or have allowed employees to publicly shame or lecture their customers.11

Government grant recipients. Religiously affiliated health care, educational and social services institutions have asserted that they must be allowed to compete for government grants and contracts without being "discriminated" against for refusing to provide all of the services that the government program is designed to offer. Among other examples, that has included receiving HIV prevention grants, but refusing to provide or educate about condoms, or even to work with other agencies that do so; receiving grants to help prevent unplanned pregnancies among adolescents, but refusing to provide complete and accurate information about contraception or to acknowledge and respect same-sex relationships; or placing children for adoption and foster care, but refusing to work with same-sex couples, or with unmarried or LGBTQ individuals.12–15

Religiously affiliated institutions broadly. A wide range of religiously affiliated institutions have asserted that they have a legal and even constitutional right to be exempted from government requirements, even those designed to prevent discrimination. Those claims have not been limited to decisions in hiring ministers and others with clearly religious duties. Rather, institutions have often demanded that they be allowed to discriminate on religious grounds even when hiring staff to fulfill government grants. Moreover, institutions have insisted that they be allowed to discriminate against LGBTQ individuals in regard to employment; to ignore same-sex marriages in providing employee benefits; to fire employees who have used abortion care, contraceptives or assisted reproductive technology, or who have had sex or become pregnant outside of marriage; or even to ignore federal law preventing discrimination on the basis of disability.16,17

Religious and moral exemptions for institutions, left unchecked, pose serious dangers for individuals and society. Proponents of religious and moral exemptions for institutions argue that no business should be forced to provide any particular type of product or service. For example, they often turn to the so-called "parable of the kosher deli," coined by USCCB, in which a requirement for employer-sponsored health plans to cover contraception is presented as equivalent to a requirement for kosher delis to sell ham sandwiches.18 Yet, what is at stake with institutional refusals is far more consequential than whether a customer can get that ham sandwich she might be craving.

Discrimination. One potential danger when health care, social services and other institutions are given religious and moral exemptions is the potential for discrimination. Because of this danger, public accommodations—such as retail stores, restaurants, schools and recreational facilities—are barred under federal and state law from discriminating against certain classes of people. That generally holds true even if that discrimination stems from religious or moral objections, as some business owners claimed in support of racial segregation. Today, the most heated discrimination-related debates are often around LGBTQ rights, with religiously affiliated hospitals, schools, adoption agencies and other institutions sometimes arguing that they should be allowed, on religious grounds, to deny some or all services to LGBTQ individuals. (One such case—involving a Colorado bakery refusing to provide wedding cakes for same-sex couples—was heard before the U.S. Supreme Court in December 2017, and a decision is expected by June 2018.19)

Power and reach. A second major issue with institutional refusals is that institutions, by their nature, have more power and reach than individuals. If one doctor at a hospital has religious objections to providing information about abortion, the hospital should be able to accommodate her by ensuring that another doctor steps in; however, if the hospital itself refuses to allow that information to be provided by anyone on staff, the patient simply will not receive that information, which interferes with her right and ability to provide informed consent for her care.

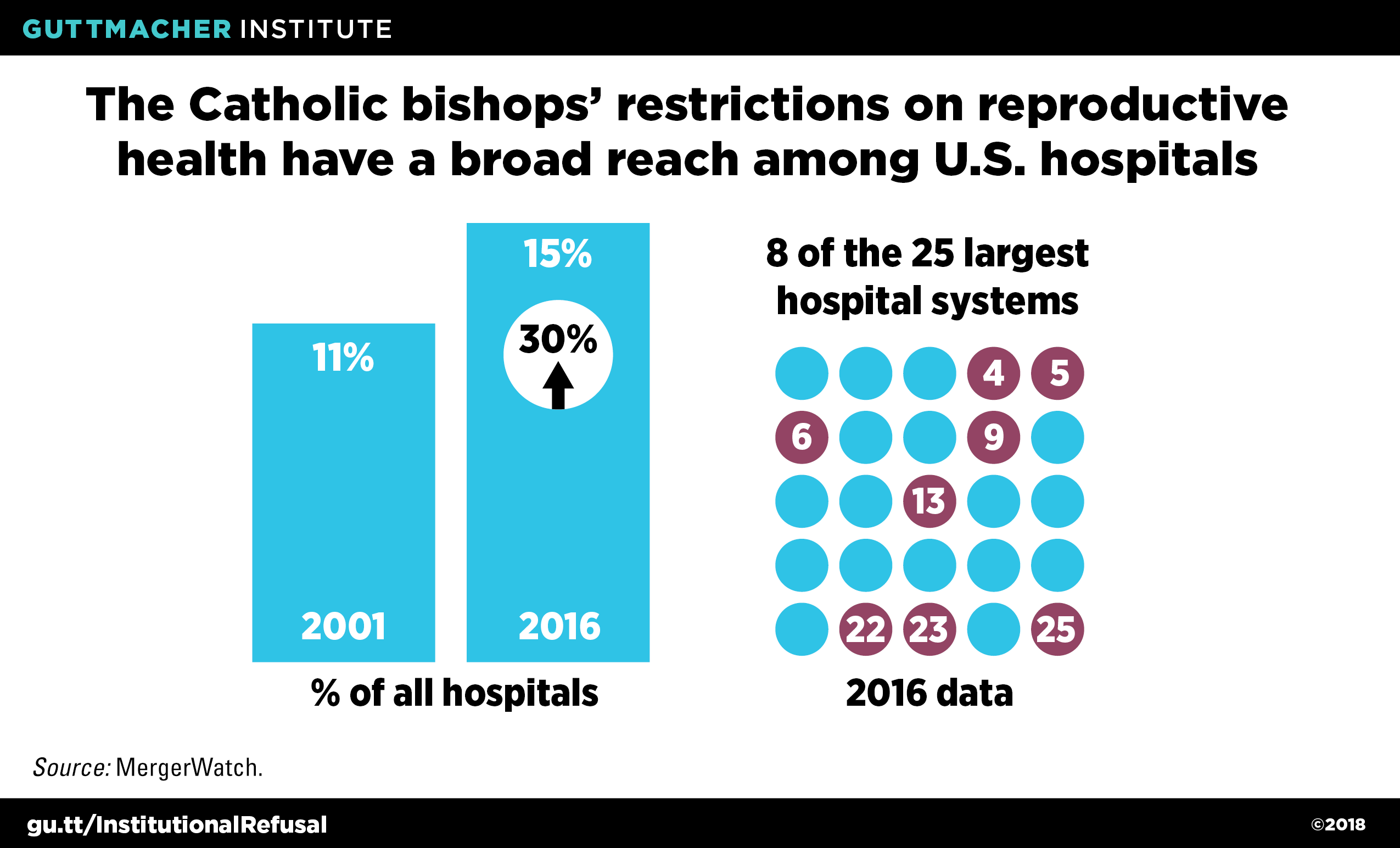

Lack of options. In some cases, a potential patient or client might be able to take her business elsewhere when faced with institutional refusal. In a large city, some customers may have a dozen pharmacies within easy reach of their home or workplace. Yet, in many cases, a hospital system, pharmacy chain, insurance company or social services agency can be the dominant or sole option in a city, county or region. For example, Catholic health systems have become an increasingly dominant force in the health care industry over the past two decades (see figure).20 In those cases, institutional refusals can leave people with no options. That might mean that patients have no place to go for immediate postpartum sterilization; that employers and families have no insurance options that cover contraceptives or abortion; that doctors have no hospitals at which they are permitted to perform gender reassignment surgery; or that local governments have no foster care agencies willing to place children with LBGTQ individuals or couples.

Even when other options seem to be available locally, institutions often have a captive audience. For example, in an emergency, an ambulance will take a patient to the closest hospital able to care for her. And enrollees in many health insurance plans are forced to seek out care within narrow insurance networks. Patients may also be "captive" through a lack of information: If a hospital withholds information about certain treatment options, the patient may never realize she is being denied care and that she would be better off seeking care elsewhere.

Undermining public priorities. Another major problem with institutional refusal is that it can be used to undermine public programs and policies. Religiously affiliated institutions have repeatedly demanded that they be allowed to receive government grants without fulfilling all the obligations of the grant—for instance, that an institution should be allowed to care for refugees or survivors of human trafficking, but deny them the reproductive health services they would otherwise be guaranteed under the grant.12 In many cases, religiously affiliated institutions have demanded that they be allowed to discriminate under a government grant in their hiring practices, either in favor of people who share their faith, or against people they view as violating the organization’s religious beliefs on issues like same-sex relations or use of assisted reproductive technologies.

When government meets those demands—couched as protections for religious institutions against discrimination by the government—it has the effect of granting the government’s imprimatur on the religious institution’s beliefs, arguably a violation of the U.S. Constitution’s Establishment Clause. Moreover, it can have the effect of allowing religious institutions to achieve policy goals that they have failed to achieve through traditional means, such as by making their case to Congress and the public.

The inherent dangers of institutional refusals must be carefully balanced with the needs and rights of others. In the current political climate, proposals to limit institutional refusals, or to establish new requirements on institutions despite potential religious objections, start off on challenging ground. Challenging does not mean impossible. For example, over the past several years, three states have enacted or expanded requirements for insurance plans to cover abortion care, and 14 states and the District of Columbia have done so for contraceptive care.21 And LGBTQ advocates continue to make advances in securing protections against discrimination, expanding coverage for transgender health care and other priorities.15 Government agencies could also improve enforcement of existing requirements, such as those around informed consent and the provision of emergency care, and could demand greater public disclosure of institutions’ refusal policies (see "Delineating the Obligations That Come with Conscientious Refusal: A Question of Balance," Summer 2009 and "Provider Refusal and Access to Reproductive Health Services: Approaching a New Balance," Spring 2008).

In the courts, the American Civil Liberties Union has spearheaded an array of efforts to push back on the use of religion to discriminate, such as through lawsuits to hold Catholic hospitals accountable to basic standards of care when pregnant women face life-threatening medical situations.22 And a broad coalition of reproductive rights and civil rights advocates spurred more than 200,000 comment letters in opposition to the Trump administration’s proposed refusal regulations.23

In addition to limiting institutional refusals, policymakers and advocates can also work to check the ability of religiously affiliated institutions to abuse their power. For instance, MergerWatch has worked for more than 20 years to protect access to reproductive health services when they are threatened by mergers between religious and secular hospitals and health systems. In some cases, they have worked with state regulators to block or unravel mergers that would result in the loss of key services; in other cases, they have helped to craft compromises to preserve those services, such as through the creation of independent institutions within or near the original secular hospital.24

Another potential approach to preventing the abuse of institutional refusal is by having the government step in to provide needed services. The United States seems unlikely to ever adopt a system where all health care institutions are run by federal, state or local governments. Yet, publicly run or publicly supported health care institutions can and do provide options for many potential patients in many parts of the country. Similarly, public insurance programs like Medicaid can ensure that at least some people have health coverage that encompasses most or all of their medical needs. And momentum appears to be building for a true single-payer system, to provide those guarantees nationwide. Unfortunately, under the wrong administration and without explicit protections for "controversial" services, government-run and government-supported coverage and services could be set up to deny care—for example, as Medicaid does now for abortion in most states.

Ultimately, securing lasting protections from the abuse of institutional refusals will require a breakthrough in a decades-long series of disputes. It must mean demonstrating to the public, the media, policymakers and the courts that many religiously affiliated institutions are abusing their power. Religious rights—like all rights—must have limits when they threaten the rights, needs and health of others. And because institutions have more power than individuals, their rights must be more carefully balanced and checked.