Since 2015, state lawmakers have begun to target the abortion method most commonly used in the second trimester, dilation and evacuation (D&E). Banning D&E is one of several trends to emerge from among the recent onslaught of state abortion restrictions, and the idea is rooted in a long history of efforts to limit access to abortion after the first trimester by enacting restrictions on specific abortion methods. Legislation to create a nationwide D&E ban was introduced in the 114th Congress, and antiabortion members of Congress—emboldened by the 2016 elections—may seize upon this tactic as part of an expansive new agenda to roll back abortion rights.

By restricting the most common method of second-trimester abortion, policymakers hostile to abortion would take a significant step forward in their campaign to eliminate abortion access in the United States. As with most abortion restrictions, the consequences would fall hardest on those already struggling to obtain access to abortion.

D&E is a safe and common method of second-trimester abortion. Dilation and evacuation is a surgical abortion procedure that takes place after the first trimester of pregnancy.1 Similar to a first-trimester surgical procedure, the patient’s cervix is dilated and suction is used to remove the fetus.2 Depending on a variety of factors (including gestational age, the extent of dilation, and providers’ training and preference), the provider might also use surgical instruments as a primary or secondary part of the procedure.1,2 Eleven percent of abortions in the United States take place after the first trimester, and national estimates suggest that D&E accounts for roughly 95% of these procedures.3,4

The safety of the D&E method was documented by the late 1970s.5 According to the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), D&E is the "predominant approach to abortion after 13 weeks," and it is "evidence-based and medically preferred because it results in the fewest complications for women compared to alternative procedures."6

Unable to ban abortion outright, abortion foes are trying to ban it method by method. Since Roe v. Wade legalized abortion nationwide in 1973, state and federal policymakers have pursued numerous strategies to restrict access. One such strategy has focused on eliminating access to abortion after the first trimester by banning one method at a time.

Missouri enacted the first method ban in 1974, the year after Roe v. Wade was decided. Missouri’s law banned what was then the most common and safest method for second-trimester abortion, saline amniocentesis. The U.S. Supreme Court ultimately struck down Missouri’s law in Planned Parenthood of Central Missouri v. Danforth in 1976, identifying it as an "arbitrary regulation designed to prevent the vast majority of abortions after the first 12 weeks." Nonetheless, as medicine and technology evolved and other abortion procedures were developed in the years following Roe v. Wade, antiabortion policymakers revived their focus on specific methods.

In the 1990s and early 2000s, state efforts to restrict access to abortion after the first trimester coalesced around bans on "partial-birth" abortion—an inflammatory term, coined by the antiabortion group National Right to Life, that has no precise medical definition. Many, but not all, of these state-level restrictions were struck down by courts, until the Supreme Court upheld a federal version in Gonzales v. Carhart in 2007. That law bans "partial-birth" abortion except when the woman’s life is endangered. The Court found the provocatively worded, but medically imprecise definition of the procedure sufficient to pass constitutional muster and applied it to the dilation and extraction (D&X) abortion method. In doing so, a majority on the Court reasoned that women would still have access to the safe and effective D&E method. In response to the decision, ACOG stated that the Supreme Court disregarded medical consensus that the D&X method is "safest and offers significant benefits for women suffering from certain conditions" and further noted that the ban "diminishes the doctor-patient relationship by preventing physicians from using their clinical experience and judgment."7

Current efforts to restrict D&E adhere closely to the "partial-birth" abortion ban playbook. As of mid-February, seven states have enacted laws essentially banning D&E; four of the bans are currently not in effect while litigation against them proceeds and a fifth is scheduled to go into effect in August.8 The bills enacted so far, as well as the federal bill introduced in 2015, follow model legislation crafted by National Right to Life. They include only very limited exceptions. In addition, while they appear to target procedures in which surgical instruments are used prior to suction, the bills do not use precise medical terminology. Rather, they employ inflammatory rhetoric designed to arouse antiabortion sentiment (for example, referring to the banned procedure as "dismemberment abortion") and leave providers with the difficult task of figuring out how to amend their practice to comply with ideological restrictions that are not grounded in science.

D&E bans interfere with providers’ medical judgment and limit options for patients. Because D&E bans are in effect in only two states and affect very few abortion providers, the impact of these policies is not yet clear. Medical groups argue that if faced with one of these bans, providers would be forced to base clinical decisions on fear of prosecution rather than on their professional medical judgment or the preferences of their patients. According to ACOG, such restrictions "limit the ability of physicians to provide women with the medically appropriate care they need, and will likely result in worsened outcomes and increased complications."6 In sum, "doctors will be forced, by ill-advised, unscientifically motivated policy, to provide lesser care to patients."

One potential modification to the procedure would require women to undergo an additional, invasive step before a D&E to induce fetal demise, such as an injection through the woman’s abdomen or cervix. Although some providers take this step when they believe it will make an abortion easier to perform in a specific case or when a patient requests it, leading authorities such as ACOG and the Society of Family Planning have concluded that the available evidence does not support induction of fetal demise as a general practice to increase patient safety.5,9

Although rarely used in the United States, another potential option is to induce labor using medication instead of performing a D&E. According to leading authorities, induction is a safe and effective method of second-trimester abortion and is sometimes preferred over D&E in specific instances, such as when burial or an autopsy is desired.5,9,10 Overall, however, induction is less common than D&E for a variety of reasons. Perhaps most significantly, induction requires a woman to experience contractions and go through labor; in addition to the emotional toll this can take, it can also be associated with greater pain and an increased risk of complications.5 And typically, induction takes longer than D&E, is more expensive, and is performed in a hospital setting.2,5 Although a patient undergoing a second-trimester abortion may not be able to choose the method used, most women select D&E when given the option between D&E and induction in research settings.5,11

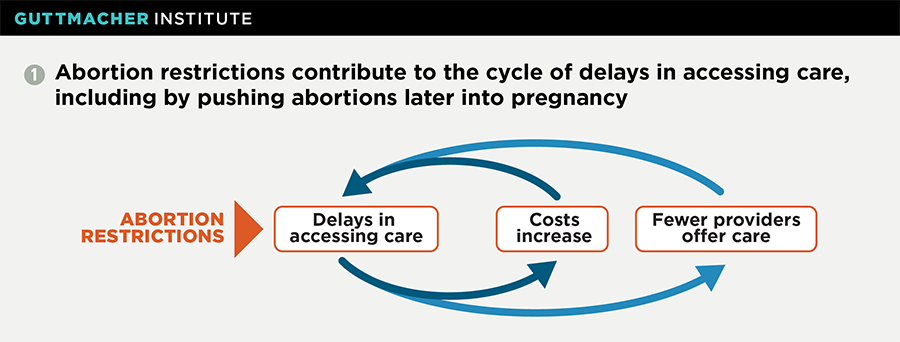

A D&E ban would compound other obstacles to abortion care. Research indicates that the vast majority of women obtaining an abortion during the second trimester would have preferred to have had it earlier.12 State abortion restrictions are one increasingly common reason women encounter delays receiving abortion care, and D&E bans must be considered in the context of such restrictions.

Restrictions that force women to delay abortion care have a disproportionate impact on low-income women, women of color and young women—which is one reason why these groups are overrepresented among women who obtain abortions during the second trimester.13 And as a woman struggles to overcome legal, financial and logistical obstacles to obtaining abortion care, the passage of time can push that care further out of reach (see chart 1). The further along a pregnancy is, the higher the cost and the fewer the providers who offer abortion services.14 A recent Guttmacher analysis found that needing financial assistance to pay for an abortion and living 25 miles or more from the facility both increased the likelihood of obtaining a second-trimester abortion.15

In addition to women who are disadvantaged in ways that limit access to services, women who receive diagnoses of fetal anomalies or maternal health complications would be disproportionately impacted by D&E bans because many of these diagnoses are received during the second trimester.

Thus, many of the women most likely to be impacted by D&E bans are already facing challenging circumstances, such as pregnancy complications or obstacles to earlier abortion care. In this way, targeting D&E could be particularly harmful as part of antiabortion activists’ larger, strategic campaign to reduce access to abortion in the United States.