Birth control is central to people’s reproductive autonomy and their ability to control whether and when to become pregnant. That autonomy is an important health benefit in its own right, and it also has numerous other health, social and economic benefits, from reducing the odds of preterm birth and other negative birth outcomes to acting as a catalyst for women’s economic and professional advancement.1

For these reasons, everyone should have health insurance that includes comprehensive contraceptive coverage. That means coverage of all contraceptive methods, services and counseling, available without coverage restrictions like copayments, usable at high-quality providers of contraceptive care, and accessible without interference from the government, employers or anyone else. In the United States, this principle has been increasingly but incompletely reflected in federal and state law through federal Medicaid requirements, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) and state contraceptive coverage requirements.

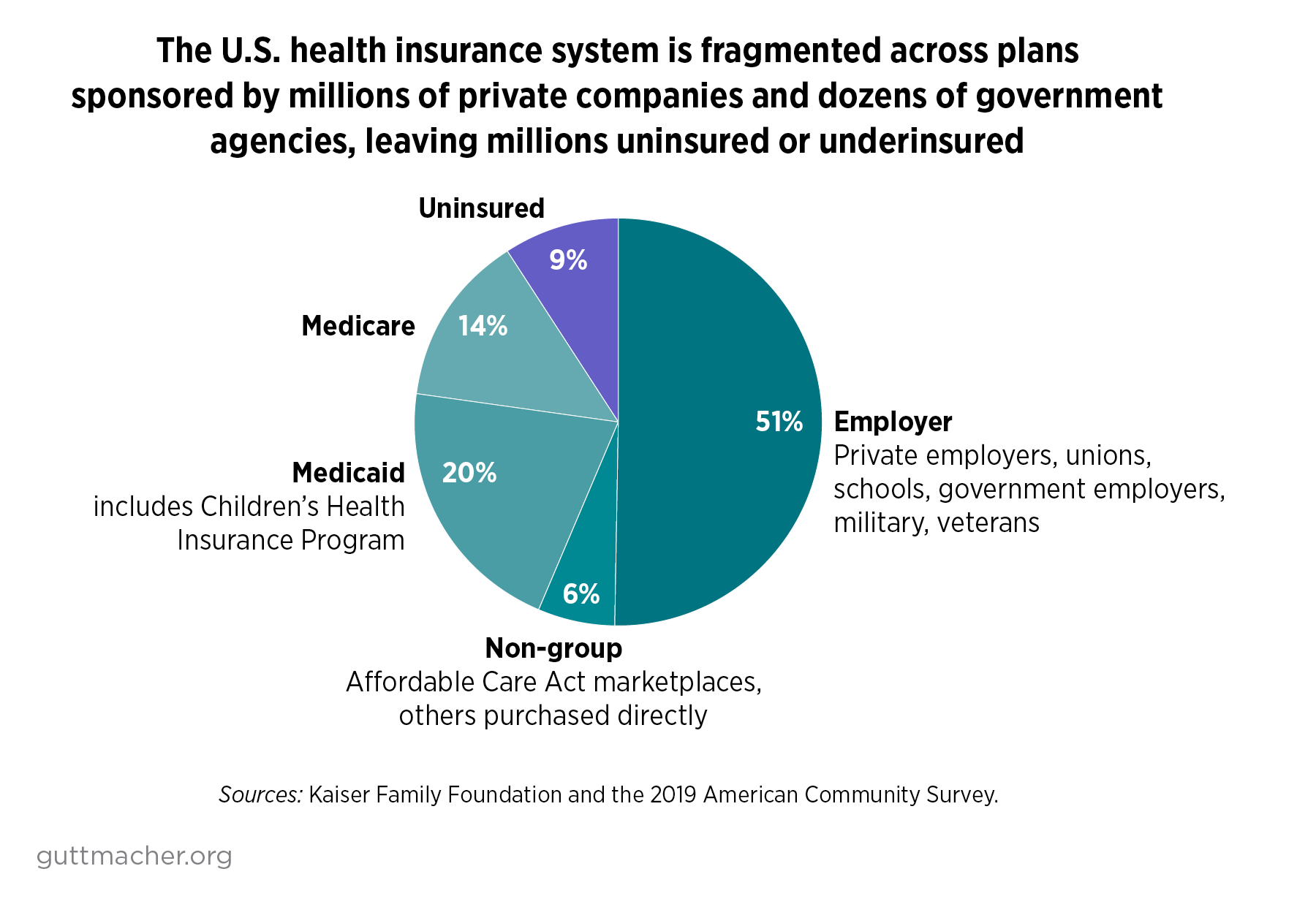

However, anticontraception policymakers have worked against contraceptive coverage requirements, as part of a coordinated campaign to eliminate affordable access to contraceptives and to tar any use of contraception as immoral.2 Moreover, gaps in federal and state requirements and persistent insurance practices have led to inconsistent and incomplete coverage. On top of all of that, the U.S. health care system is fragmented, complex and inequitable, leaving many people uninsured or underinsured, and those foundational problems extend to birth control coverage.

Many of these problems can and must be addressed by the incoming Biden-Harris administration, through regulations and guidance to improve and enforce coverage requirements in Medicaid, private insurance plans and other types of federally regulated or administered coverage. To fully realize the principle of comprehensive insurance coverage of contraceptives—and to ensure that it remains in place in the future—the new administration must work with its allies in Congress to develop and enact a federal law that guarantees the highest quality of contraceptive coverage for everyone in the United States, regardless of who they are, where they live or how they get their health insurance.

Current State of Contraceptive Coverage

People in the United States rely on health insurance plans from a wide array of sources: private insurance companies, employers, schools, the federal government, state governments and other institutions. This patchwork nature leads to multiple serious problems.

Most notably, tens of millions of people in the United States fall through the cracks and end up uninsured (see figure).3 In addition, the complexity of the U.S. health insurance system makes it difficult to monitor, regulate and fix, and leads to wide variations in coverage requirements and coverage in practice. For individuals and families, all of these structural issues result in confusion, insecurity, high costs and severe inequities, with many people—especially people with low incomes, people of color and other marginalized populations—not having their needs fully met. These broader problems extend to coverage for contraceptives, and are compounded by political and ideological attacks on contraceptives and other reproductive health care.

Private Insurance

Most U.S. residents have health insurance provided through an employer or school or purchased directly from an insurance company, often through the ACA’s health insurance marketplaces.3 The large majority of these private insurance plans are subject to the ACA’s contraceptive coverage requirement.

The ACA requirement is part of a broader provision that requires private health plans to cover a wide range of preventive health services. In 2011, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) adopted recommendations from a panel of the Institute of Medicine (now called the National Academy of Medicine) about what should be included as preventive services for women, a list that included the full range of contraceptive methods, counseling and services.4 All of these preventive services, including those related to contraceptives, must be covered without copayments, deductibles or other out-of-pocket costs for patients.

Although the ACA requirement applies to most private insurance plans, there are some exceptions: As of 2019, 13% of workers with employer-sponsored coverage were enrolled in a "grandfathered" plan that was exempt from many ACA requirements, including for contraceptive coverage.5 Also, plans established by houses of worship and some other religiously affiliated nonprofits, known as "church plans," are exempt from federal enforcement under the ACA’s preventive services requirement.6 In addition, Trump-Pence administration regulations finalized in 2018 provide sweeping exemptions to plans offered by employers and schools that have religious or moral objections to some or all contraceptive methods.7 Multiple lawsuits challenging these exemptions are still making their way through the courts in the wake of a July 2020 U.S. Supreme Court decision that upheld the Trump-Pence administration’s authority to issue the regulations.

In addition to the ACA requirement, 29 states and the District of Columbia have their own contraceptive coverage requirements for private insurers, many dating back to the mid-1990s.8 These state-level requirements do not apply to many types of private insurance coverage—most notably, federally regulated "self-insured plans," in which employers take on financial risks themselves, rather than buying traditional insurance from a separate company—but they apply in some instances to plans that are not subject to the ACA requirement.

Medicaid

The second most widely used insurance source for birth control is Medicaid, jointly run and paid for by the federal and state governments. The coverage provided to many Medicaid enrollees—principally, most people included in the ACA’s broad expansion of Medicaid coverage to adults with incomes at or below 138% of the federal poverty level—is subject to the ACA’s contraceptive coverage requirement.

Other Medicaid enrollees’ coverage is only subject to a less-specific requirement, established by Congress in 1972, that states cover family planning services and supplies without out-of-pocket costs. In 2016, the Obama-Biden administration issued regulations and guidance offering more details about patients’ rights to a choice of family planning services and providers.9 Nevertheless, numerous decisions about contraceptive coverage continue to be left to state governments and the private companies that run Medicaid managed care plans.10

Other Types of Coverage

Private insurance and Medicaid are the two dominant types of health insurance for people of reproductive age, but there are many other types of health coverage in the fragmented U.S. system. For example:

- Medicare: The federal Medicare program covers several million people with disabilities, but has been designed primarily for an elderly population and does not appropriately cover contraceptive care or other sexual and reproductive health services.11

- Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP): CHIP is a public insurance program for children and, in some states, pregnant women. Some CHIP plans are subject to Medicaid requirements, including for contraception, while others are run with more flexibility for state-level decisions. Almost all state CHIP plans cover contraceptives, with the notable exception of Texas.12

- Federal employees: The federal government provides coverage for millions through its civilian Federal Employees Health Benefits (FEHB) Program, the military TRICARE program and the Veterans Administration. Each of these programs has its own unique coverage rules, and all include some (but not comprehensive) coverage for contraceptive methods and services.11,13

Government agencies are also involved in providing health coverage or direct medical care—including for birth control—for state and local employees; people in prisons, jails and immigration detention; Indigenous populations at Indian Health Service facilities; faculty and students at public schools and universities; and uninsured people, through public and nonprofit clinics, including those supported by the Title X family planning program.

The Principle of Comprehensive Coverage

This varied landscape of health insurance coverage and requirements results in inconsistent and incomplete coverage for contraception. Most plans do not fully satisfy the components of comprehensive coverage in terms of the scope of services covered, the financial and other restrictions allowed, the choice of providers offered or the protections from interference that are in place.

Scope of Services

Everyone should have insurance coverage for the complete range of contraceptive methods, services and counseling, so they can choose a method that works best for them and thereby use it most effectively. This coverage should include every distinct method as categorized by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), a list that ranges from surgical sterilization to prescription birth control pills to over-the-counter (OTC) condoms and spermicides.14 It should also include provision of information and counseling about contraceptive decision making, the benefits and drawbacks of each method, how to use a given method and how to get follow-up questions answered. And it should encompass all services needed to begin, continue or stop using a particular method, such as insertion and removal of an IUD, and any tests needed, such as a blood pressure check, before prescribing a specific method.

The rules and guidance governing the ACA’s contraceptive coverage requirement include most of these details.15 However, HHS has excluded vasectomy and external condoms from its list of covered methods, arguing that they are controlled by men and therefore do not count as women’s preventive services under the law. In addition, the FDA list has not been kept up to date and as of January 2021 excludes several recently approved methods, including a contraceptive gel, a contraceptive ring that lasts a full year and an FDA-approved mobile app that tracks fertility.16,17

State contraceptive coverage laws vary widely in their requirements, but several include protections that go beyond what is required by the ACA, with eight states requiring coverage for vasectomy and four states and the District of Columbia requiring coverage for external condoms.8

Federal Medicaid law does not explicitly require states to cover any specific contraceptive methods. However, federal regulations state that Medicaid enrollees must be "free from coercion or mental pressure and free to choose the method of family planning to be used,"18 and Obama-Biden administration guidance made it clear that states should cover every method and must cover necessary services such as removal of an IUD or implant.9 In practice, most states cover the full range of methods, including vasectomy and external condoms.10

Coverage Limitations

A second component of the principle of comprehensive contraceptive coverage is that no one should face financial or other bureaucratic barriers to using their coverage—barriers that are all too common in U.S. insurance plans. That should mean no copayments, deductibles or other out-of-pocket costs. It should mean coverage for an extended supply of contraceptives—ideally, a full 12 months—to eliminate unnecessary trips to the pharmacy, and there should not be medically inappropriate limitations on quantity or frequency. Under this principle, coverage of OTC methods should be included without the extra step of obtaining a prescription, and other types of gatekeeping (known as "medical management techniques") should not be allowed, such as prior authorization from an insurance company. And there should be coverage for everyone, regardless of age or gender. In particular, that would bar insurance practices—sometimes justified by interpreting the ACA’s contraceptive coverage requirement as limited to women—that discriminate against transgender or nonbinary patients.

Federal rules and guidance for the ACA contraceptive coverage requirement specifically lay out many of these protections—for instance, federal guidance specifically bars insurers from denying coverage based on sex assigned at birth, gender identity or gender as recorded by the insurer—and the exemption from out-of-pocket costs is required by the ACA statute for plans that fall under its purview.15,19,20 Nevertheless, HHS guidance does not require plans to cover a 12-month extended supply or OTC methods without a prescription, and it limits but does not prohibit all types of medical management techniques.

Several state laws go beyond the ACA requirements in protecting patients against insurance limitations. Most notably, 20 states and DC require insurers to cover an extended supply of contraceptives at one time.8

The Medicaid statute clearly exempts family planning services and supplies from having out-of-pocket costs, including in privately run managed care plans. And HHS has interpreted the regulatory protections against contraceptive coercion to specifically bar or discourage many coverage limitations, including prior authorization, step therapy (requiring that a patient try one method and fail with it before trying the method of their choice), inappropriate quantity limits (such as covering only one IUD every five years, even if a previous IUD was expelled or removed for a planned pregnancy) and restrictions on changing one’s contraceptive method.9 Some state Medicaid programs cover OTC methods without a prescription.10

Access to Providers

A third component of comprehensive contraceptive coverage is that everyone should be able to access their choice of high-quality providers of contraceptive care. Most U.S. health insurance plans rely on closed networks of providers, and those networks should be required to include providers with family planning expertise, including with surgical sterilization and devices like IUDs and implants. Patients should be able to easily identify and obtain appointments with family planning experts, without referrals from a primary care provider or other delays. Insurance plans should not be allowed to discriminate against health care providers for reasons beyond their ability to provide needed care, such as by excluding providers that also offer abortion, and plans should be required to offer a level of reimbursement for all providers that covers their costs and encourages them to serve patients.

Private insurance today does not fully meet this standard and has been trending in the wrong direction, toward restrictive provider networks. The ACA requires most private plans to grant patients direct access to obstetric and gynecologic health care providers without a referral, building on prior laws in most states. ACA marketplace plans are also required to maintain adequate provider networks, including many publicly supported health centers, but the details of those standards are mostly left to the states and do not adequately protect access to family planning providers.21

By contrast, federal Medicaid law and regulations guarantee that enrollees can obtain family planning care, without referral, from the qualified Medicaid provider of their choice, even if that provider does not contract with their Medicaid managed care plan.9 And Obama-Biden administration regulations and guidance include specific protections designed to ensure that managed care plans have sufficient obstetrician-gynecologists and family planning providers in their networks. Yet, the Trump-Pence administration rescinded 2016 guidance that had made it clear that state Medicaid agencies could not exclude Planned Parenthood and other abortion providers for reasons unrelated to their ability to provide services, and allowed Texas to do just that for part of its Medicaid program.22 The Medicaid reimbursement rates set by states and managed care plans are also notoriously and inadequately low, negatively impacting patients’ ability to find a health care provider.23,24

External Interference

A fourth component of the principle of comprehensive contraceptive coverage is that patients can use their coverage without interference or coercion from anyone—the government, an employer or school, an insurance plan, a health care provider or a family member. That means curbing the harm of exemptions based on religious or moral grounds, which allow many of those actors to withhold contraceptive coverage entirely.25 It means having explicit protections against discrimination by providers and health insurance plans.26 Eliminating interference also means including strong confidentiality protections for individuals insured as a dependent on a parent’s or partner’s health plan, so patients can feel safe using their insurance.27 And it means ensuring that coverage is shielded against political interference, such as by including all necessary details in federal and state law, rather than relying on regulations or guidance that can be changed by a hostile executive branch.

Both the ACA and Medicaid have at best limited protections on these fronts. The Trump-Pence administration has greatly expanded religious and moral exemptions from providing contraceptive coverage1 and reproductive health coverage and care more generally.26 Similarly, the ACA includes nondiscrimination protections, but the Trump-Pence administration has attempted to undermine them, especially for reproductive health care and for LGBTQ patients.

Medicaid law and regulations have long been interpreted as protecting confidentiality, including for adolescents, and federal health privacy protections give patients the right to receive communications via alternative means or locations (such as via email rather than by paper mail at a home address).28 Yet, routine communications in Medicaid and private insurance, particularly explanation of benefits forms (EOBs) and other information around billing, can inadvertently violate confidentiality27 and only a few states have taken specific action to prevent this from happening via EOBs.29

Finally, many details of federal contraceptive coverage requirements—including the designation of birth control as a preventive service that must be covered under the ACA—are only contained in regulations and guidance and are at the mercy of future federal administrations.

Oversight and Enforcement

Intrinsic to the principle of comprehensive contraceptive coverage is robust oversight and enforcement of all aspects of any coverage requirement. To that end, government agencies and outside researchers must be able to assess what health insurance plans are doing, and government agencies and courts must have the tools, resources and mandate to enforce requirements.

For both private insurance and Medicaid, oversight and enforcement of existing contraceptive coverage requirements have been far from sufficient. The federal government does not collect any information about the extent to which private health plans or Medicaid plans are covering contraceptive methods, services and counseling, and private researchers have had infrequent and incomplete access to such data.

Even under the Obama-Biden administration, officials in HHS, the U.S. Department of Labor and the U.S. Department of the Treasury made few public efforts to enforce the ACA’s contraceptive coverage requirement, beyond issuing guidance and defending it in court, and neither did most state insurance regulators. The fact that so many agencies have partial jurisdiction over the requirement may have contributed to the lack of enforcement. During the Obama era, HHS enforced Medicaid’s free choice of provider requirement by denying state requests to exclude abortion providers from the program and warning states that threatened to do so without federal permission, but its enforcement powers over state Medicaid agencies are generally limited.

What Policymakers Can Do

Biden-Harris Administration

Federal officials at the White House, HHS, Labor Department and the Treasury Department should reinstate and bolster federal regulations and guidance to support the principle of comprehensive contraceptive coverage, provide robust oversight and enforcement of federal requirements, and use the megaphone of the presidency to make it clear why this principle is important.

As laid out above, important aspects of this principle are already in place for private health insurance and Medicaid, and could be strengthened purely through executive branch authority. Many specific steps have been outlined in the Blueprint for Sexual and Reproductive Health, Rights and Justice, which was developed in 2020 by more than 90 organizations, including the Guttmacher Institute.30 Several of the most important early steps include rescinding harmful Trump-Pence administration regulations around contraceptive coverage, religious and moral exemptions, and the ACA’s nondiscrimination protections, and reinstating the Obama-Biden administration guidance clarifying that states cannot simply kick Planned Parenthood out of the Medicaid program as a provider.

Notably, the Trump-Pence administration has pushed the boundaries of executive branch authority in ways that could allow the Biden-Harris administration to take bold action. For example, the U.S. Supreme Court decision in Little Sisters of the Poor v. Pennsylvania—which validated the Trump-Pence administration’s authority to issue its sweeping religious and moral exemptions to the federal contraceptive coverage guarantee—appears to give HHS considerable leeway in reinterpreting the guarantee in more positive ways in order to strengthen and expand its requirements.

The Biden-Harris administration—with vocal support from the president and vice president—should also commit to greater coordination, oversight and enforcement of comprehensive contraceptive coverage across all federal programs. For example, many outside experts and advocacy groups have recommended that the administration set up a new White House office to coordinate policy and programs on sexual and reproductive health and rights, and to oversee an interagency working group. That office and working group should be tasked with extending the principle of comprehensive contraceptive coverage as consistently and fully as possible across every relevant federal agency and program, including Medicare, CHIP, FEHB, TRICARE, Veterans Administration, the Indian Health Service, federal prisons and immigration detention centers, and more.

Congress

However much progress the new federal administration makes, some problems are likely too big for the executive branch to handle on its own. And the fragmentation and complexity of the U.S. insurance market mean that fixing these problems piecemeal may end up actually increasing inequities, if the programs that marginalized populations rely on are the ones that prove most difficult to fix. Moreover, fixes by one administration can be unwound by the next administration.

Therefore, to fully realize the principle of comprehensive contraceptive coverage for everyone in the United States, we need to work toward a legislative solution that would apply every aspect of this principle to every type of insurance coverage, and do so regardless of who sits in the Oval Office. That could be accomplished through stand-alone legislation that provides details about the different components of comprehensive contraceptive coverage and how to apply them to each type of health insurance and federal health program, and provides additional funding for programs like Title X that serve people without health insurance at all. Such a bill could also serve as a rallying point for advocates and lawmakers at both the federal and state levels, in order to build momentum until there are enough supporters of full contraceptive coverage in Congress to get a bill enacted.

Another option would be to incorporate this principle through a broader health care reform solution,31 such as the Biden-Harris plan for health insurance32 or Medicare for All.33 The new public health insurance options that would be established by these proposals must be explicitly required to cover the full scope of contraceptive methods, services and counseling, without financial or bureaucratic barriers, at a choice of high-quality health care providers, and without external interference, including from future federal administrations. That solution might not merely bypass the fragmentation and gaps in the current U.S. health insurance system, but make significant progress toward fixing them.