In 1994, at the convening of the International Conference on Population and Development (ICPD), 179 countries coalesced around a global consensus and program of action that shifted away from emphasizing numeric population targets and instead focused on dignity and human rights—including the right to plan one’s family—as fundamental to development. As we approach the 25th anniversary of ICPD in 2019, attainment of such needs and rights remains elusive for far too many people. Around the world, more than 200 million women who want to avoid pregnancy face an unmet need for modern contraception.1 Each year, approximately 1.8 million people acquire new HIV infections, more than 350 million people need treatment for curable STIs, and approximately 266,000 women die from cervical cancer.2,3 And it is those who are oppressed, discriminated against or otherwise marginalized in society whose needs are too often ignored.

Addressing these and other sexual and reproductive health and rights gaps and needs is fundamental to people’s health and survival, to advancing economic development, and ultimately to the well-being of humanity. Although ICPD broke new ground, subsequent United Nations (UN) agreements—including the UN’s current development agenda, the Sustainable Development Goals—have fallen short and do not reflect a comprehensive commitment to ensuring health or individual and community rights. Moreover, in the United States, the Trump administration is pushing an agenda domestically and abroad that threatens these health and rights advancements and adds additional barriers to those already present in laws, policies and social norms.

It is within this context that the Guttmacher-Lancet Commission on Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights released its report in May 2018.4 This assembly of global health, development and human rights experts calls on national governments, international agencies, donors, civil society groups and other key stakeholders to commit to a bold agenda to achieve universal access to sexual and reproductive health and rights. The Commission is an international collaboration that brought together 16 experts from all regions of the world to put forth an evidence-based, forward-looking vision that is affordable, attainable and essential to the achievement of health, equitable development and human rights for all.

A Visionary Definition

Knowing how to meet people’s needs begins by appropriately defining them. The Guttmacher-Lancet Commission builds on previous definitions, such as those from the World Health Organization, and defines sexual and reproductive health and rights in a bold new way. It describes sexual and reproductive health as "a state of physical, emotional, mental, and social wellbeing in relation to all aspects of sexuality and reproduction, not merely the absence of disease, dysfunction, or infirmity," and emphasizes that "a positive approach to sexuality and reproduction should recognise the part played by pleasurable sexual relationships, trust, and communication in the promotion of self-esteem and overall wellbeing."4

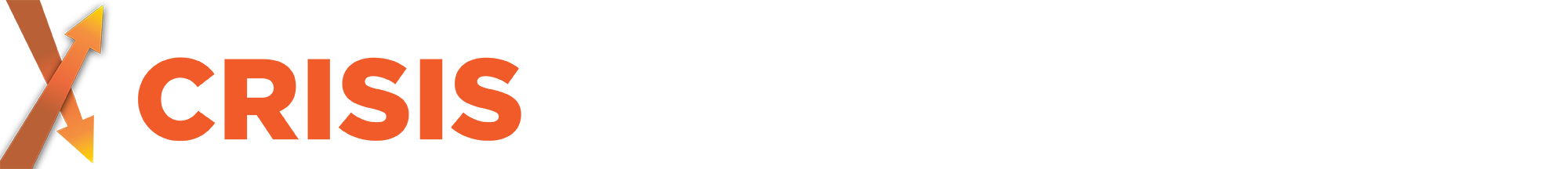

The Commission’s approach is unique in integrating four distinct components—sexual health, sexual rights, reproductive health and reproductive rights—into a comprehensive definition (see figure 1), which recognizes that "achievement of sexual and reproductive health relies on the realisation of sexual and reproductive rights, which are based on the human rights of all." Specifically, the definition includes the rights of all individuals to: 4

- have their bodily integrity, privacy and personal autonomy respected;

- freely define their own sexuality, including sexual orientation and gender identity and expression;

- decide whether and when to be sexually active;

- choose their sexual partners;

- have safe and pleasurable sexual experiences;

- decide whether, when and whom to marry;

- decide whether, when and by what means to have a child or children, and how many children to have; and

- have access over their lifetimes to the information, resources, services and support necessary to achieve all the above, free from discrimination, coercion, exploitation and violence.

The definition includes rights that are often overlooked around issues like bodily integrity, sexual pleasure, sexuality and identity. In addition, it addresses issues such as violence, stigma and bodily autonomy as connected both to health and to individual rights. The definition offers a comprehensive and universal framework to guide governments, UN agencies, civil society and others in designing policies, services and programs that address all aspects of sexual and reproductive health and rights effectively and equitably.

Essential Interventions

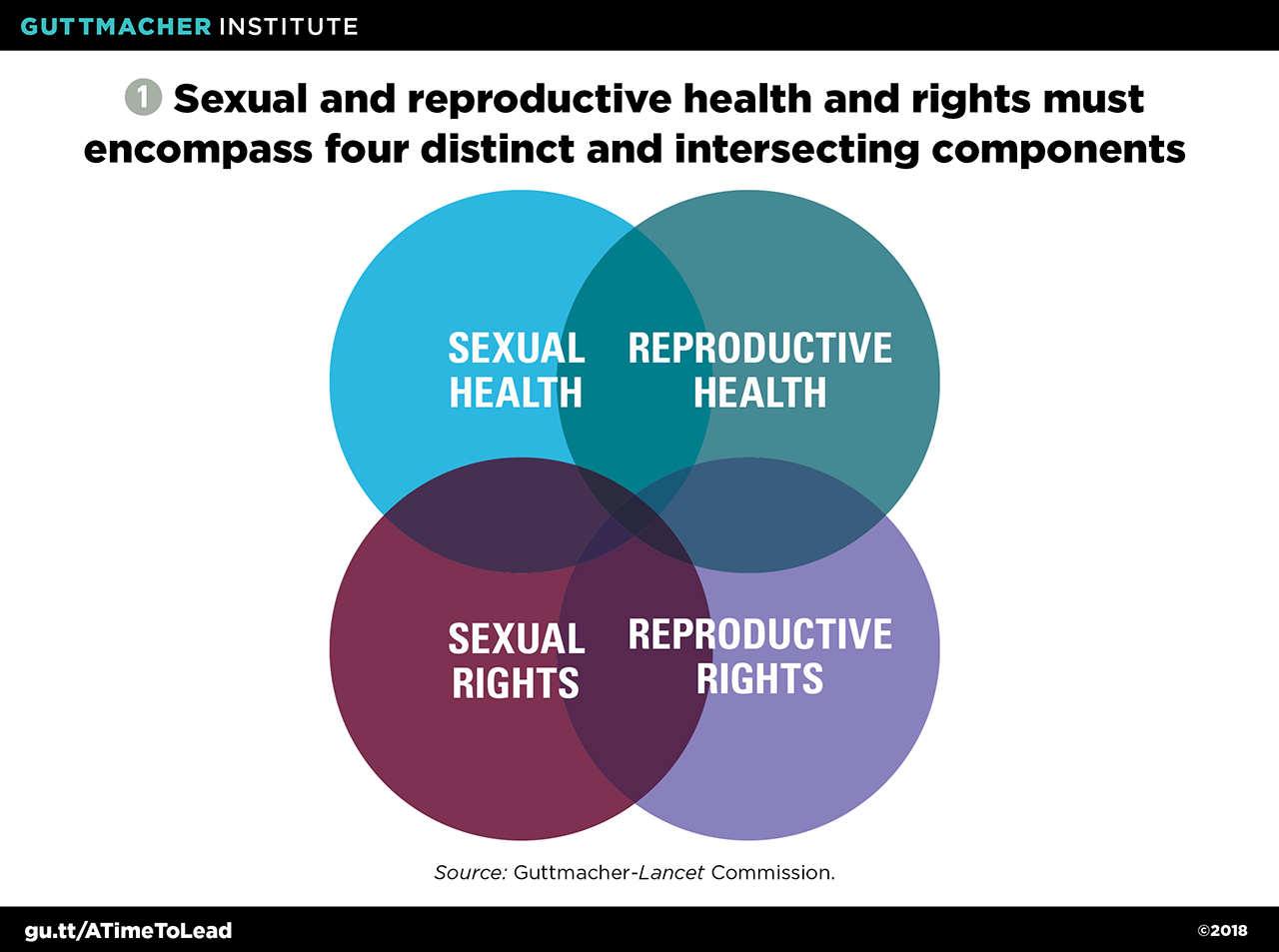

With the new visionary definition as a foundation, the Guttmacher-Lancet Commission presents a package of essential sexual and reproductive health interventions.4 The proposed package includes components that countries often focus on with relation to sexual and reproductive health, such as promoting contraceptive access, HIV prevention and treatment, and maternal and newborn health care. Additionally, the package includes often-overlooked or politicized components—such as abortion, infertility services, comprehensive sexuality education and gender-based violence interventions—that are also critical to ensuring sexual and reproductive health and well-being (see figure 2).

The United States has a long history as a worldwide leader in promoting access to several of these essential interventions, and it continues in this capacity to some extent today. For example, the federal government has promoted counseling and services for a range of modern contraceptives, both domestically through the Title X national family planning program and globally through the U.S. Agency for International Development’s (USAID) family planning and reproductive health bilateral assistance. When it comes to HIV, the United States has played a critical leadership role in providing resources, research, and prevention and treatment interventions through such domestic efforts as the Ryan White HIV/AIDS program and globally through the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR). The U.S. government has also led efforts to prevent and address gender-based violence at home and abroad through the domestic Violence Against Women Act, USAID’s gender-based violence prevention and response programming and PEPFAR’s Determined, Resilient, Empowered, AIDS-free, Mentored, and Safe women (DREAMS) initiative. In addition, the United States has been a leader in addressing reproductive health needs and related violence prevention efforts in humanitarian settings; for instance, in 1995 the U.S. government provided funds to establish the Inter-Agency Working Group on Reproductive Health in Crises, a consortium of nongovernmental organizations, donors, governments and UN agencies.

Despite these and other examples of U.S. leadership, there are additional sexual and reproductive health and rights areas and interventions that the United States has yet to address on a scale commensurate with need, and in some instances even restricts. For example, the United States has provided little investment and leadership, domestically or internationally, related to information, counseling and services for subfertility and infertility. And, rather than ensuring safe abortion services and treatment for complications of unsafe abortion, the U.S. Congress instead restricts insurance coverage of abortion domestically through numerous provisions, including the Hyde Amendment, and limits access to abortion care globally through a funding restriction known as the Helms Amendment.

Even when the United States is attempting to support sexual and reproductive health and rights, these efforts are not well integrated. U.S. policy and resource allocation is often piecemeal and siloed: For instance, investment in international bilateral family planning and reproductive health assistance is separate from HIV prevention and treatment under PEPFAR. Although integration can and often does happen on the ground, U.S. global health programs are seldom designed to provide the full spectrum of services.

Overlooked and Underserved

Addressing the full range of people’s sexual and reproductive health and rights needs and providing access to a comprehensive package of interventions is an enormous challenge. For example, the 25 million unsafe abortions worldwide each year demonstrate the failures of countries’ systems and policies to uphold the right of individuals to be informed about and seek safe abortion options.4 Further, at some point in their lives, about one in three women worldwide experience gender-based violence, most often from an intimate partner. Ultimately, almost everyone of reproductive age—some 4.3 billion people, more than half the world’s population—will lack at least one essential sexual or reproductive health service over the course of their reproductive life.

The Guttmacher-Lancet Commission report makes clear that countries—including the United States—are at varying stages in addressing sexual and reproductive health and rights challenges.4 One critical step forward is to focus resources on historically marginalized and underserved populations who face greater obstacles in accessing sexual and reproductive health services. Such populations include adolescents, LGBTQI individuals, displaced people and refugees, racial and ethnic minorities, people with disabilities, sex workers, people who use drugs, immigrants and indigenous peoples.

The U.S. government has taken some positive steps to address the needs of some of these key populations internationally, such as launching the USAID LGBT Vision for Action in 2014, which outlined the agency’s commitment "to include LGBT considerations in every area of our work, and in every place we work."5 The PEPFAR program also has a history of exploring new approaches to support marginalized and underserved people and communities, such as by supporting a methadone maintenance program to prevent HIV among injection drug users in Tanzania in 2011, the first of its kind in Sub-Saharan Africa.6 Focusing support on marginalized communities is also a priority among some domestic U.S. programs. The Title X family planning program, for instance, seeks to provide services to low-income patients, adolescents and other underserved populations. And among adolescents, the Personal Responsibility Education Program prioritizes interventions seeking to serve "vulnerable and culturally under-represented youth populations."7

Although the data are limited, it is clear that marginalized populations face challenges in availability and ability to access sexual and reproductive health education and services. As a result of these challenges and other systemic barriers to care, these populations often suffer disproportionately poor health outcomes.4 In addressing these challenges and barriers, it is essential to approach each population not as a homogenous group, but rather as individuals with unique identities—each often facing numerous forms of marginalization and oppression. Equally important, marginalized individuals must be the ones to lead in the development of policy and program solutions for themselves, their families, and their communities.

Fortunately, the cost of meeting people’s sexual and reproductive health and rights needs is financially achievable. In low- and middle-income countries, the average annual cost per person for meeting all women’s needs for contraceptive, abortion, and maternal and newborn health care would be $8.52.4 In fact, according to a Guttmacher Institute estimate, every additional dollar invested in contraception above the current level of services saves $2.20 per person in pregnancy-related care.1 This would mark an achievable investment by the United States, other governments and international donors in support of family planning and reproductive health services globally.

Leader or Threat?

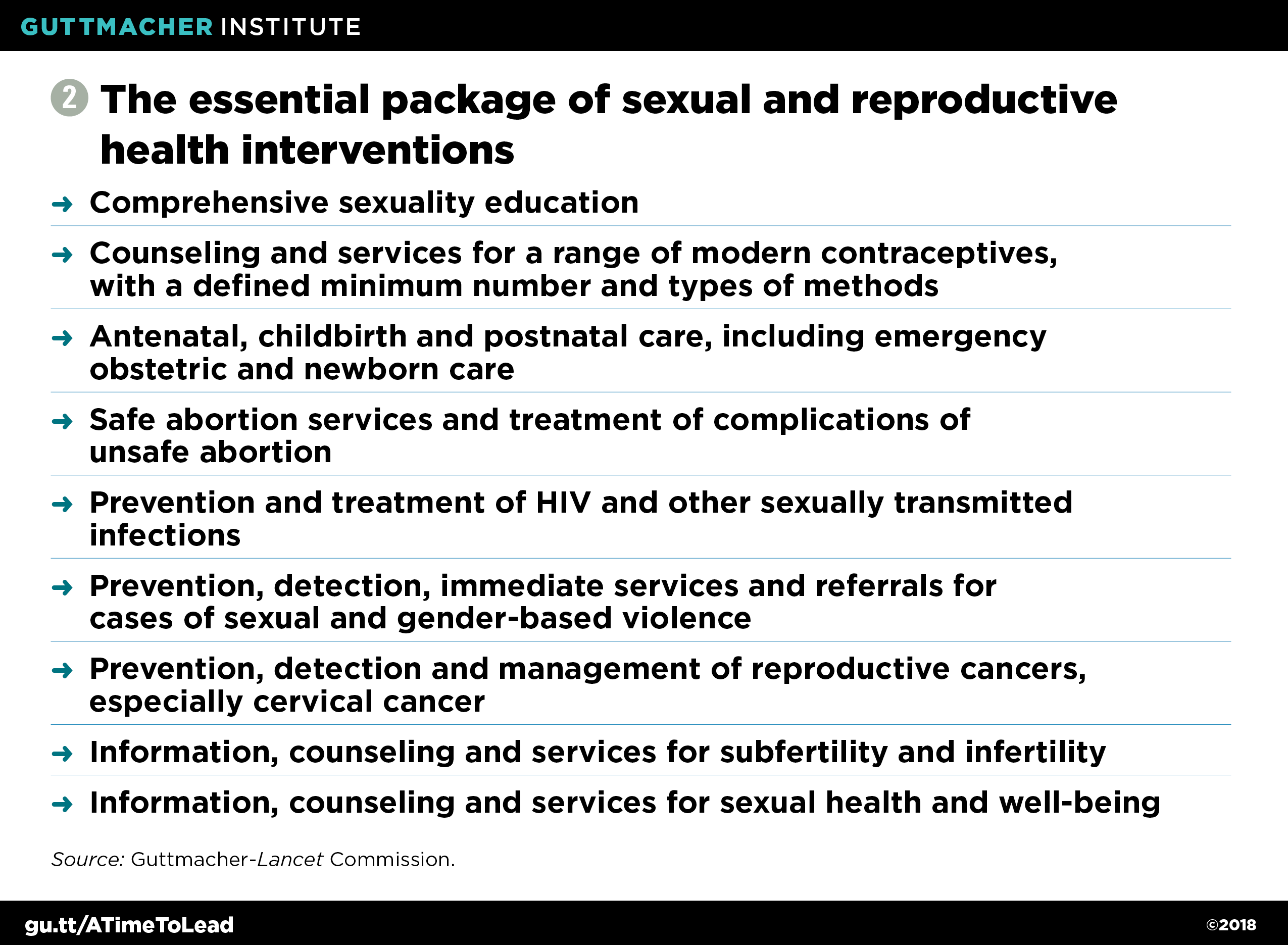

For more than 50 years, the United States, and in particular USAID, has had a track record of support for international family planning and reproductive health programs that—while not immune to the political whims of presidential administrations and congressional majorities—has markedly improved the well-being of women, families and societies in developing countries. This achievement is jeopardized by Trump administration policies that not only impede future progress, but also reverse the United States’ previously held goals of improving health and advancing human rights worldwide (see figure 3).

To date, the Trump administration has reinstated and expanded the global gag rule,8 threatening provision of health services in low-income countries; blocked funding for the United Nations Population Fund,9 one of the leading providers of sexual and reproductive health services around the world, particularly in areas of conflict;10 and proposed drastic cuts (up to complete elimination) for bilateral family planning and reproductive health assistance funding.11 This pattern of attacks on sexual and reproductive health and rights is all too evident domestically as well, including through efforts to undermine the Title X family planning program,12,13 eliminate the Teen Pregnancy Prevention Program,14 and dismantle public and private insurance coverage of sexual and reproductive health services.15

The harmful policies and ideologically motivated agenda of the Trump administration to obstruct health and rights advancements globally have already had far-reaching implications. Thus far in 2018, the United States has pushed for the removal of the phrase "sexual and reproductive health" from annual multilateral agreements such as at the UN Commission on the Status of Women, and it has contributed last-minute resistance at the UN Commission on Population and Development, resulting in failure to produce a consensus outcome document.16 The United States’ retraction from leading efforts to elevate sexual and reproductive health and rights within global human rights frameworks was further exemplified by the removal of reproductive rights from the U.S. State Department’s annual Human Rights Reports, as well as the country’s withdrawal from membership on the UN Human Rights Council.17,18

As countries strive to achieve collective and comprehensive progress on sexual and reproductive health and rights, leadership by the United States and others in the global community is crucial. Such U.S. commitment to lead would be welcome on the eve of the 25th anniversary of the landmark ICPD Program of Action, as countries once again reassess the path toward achieving the principles set out at that conference: investing in and improving the quality of life for women and girls, affirming the importance of sexual and reproductive health as essential to women’s empowerment, and highlighting the linkages between sexual and reproductive health and rights and every other aspect of population and development, among others.

The roadmap is available: The Guttmacher-Lancet Commission report puts forward a global vision for advancing sexual and reproductive health and rights. Its adoption and implementation is dependent on individuals demanding their rights, on civil society organizations and advocacy groups supporting those rights, and on governments respecting, protecting and fulfilling those rights. The United States has the history and ability to lead future progress in this arena. The federal government can begin by reversing course on its restrictive policies, increasing investment in sexual and reproductive health and rights programs focused on marginalized populations and holistic approaches, and once again stepping up as a global leader in advancing the health and rights of people both at home and around the world.

The report on which this article is based was made possible by support to the Guttmacher Institute from the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs, UK Aid from the UK Government, the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation, The William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency, the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development, and The David and Lucile Packard Foundation. The findings and conclusions in the report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the positions and policies of the donors. This article draws on the work of Guttmacher-Lancet Commission, but reflects the views of the Guttmacher Institute.