Unsafe abortion continues to be a major cause of maternal mortality and disability—accounting for 13% of pregnancy-related deaths worldwide.1 Every year, 47,000 women die because of unsafe abortion and millions more face injuries, including hemorrhage, infection, chronic pain, secondary infertility and trauma to multiple organs. Of the 38 million abortions performed annually in developing countries, more than half are unsafe (56%); in Africa and Latin America, virtually all abortions are unsafe (97% and 95%, respectively).1 The World Health Organization (WHO) defines an unsafe abortion as one performed by an individual without the necessary skills, or in an environment that does not conform to minimum medical standards, or both.2

A holistic approach to reducing the number of abortions that are unsafe and minimizing the consequences of those that still take place has at least three major components. First, improving access to quality family planning services to prevent more unintended pregnancies in the first place would mean fewer abortions overall— including those that are unsafe—because almost all abortions are preceded by an unintended pregnancy.1 Second, ensuring that safe abortion care is more widely available would mean fewer women would need to resort to unsafe, usually clandestine alternatives. Finally, enhancing the quality and availability of comprehensive postabortion care—including treatment for the complications associated with incomplete abortions—would substantially mitigate the harms that too often result from unsafe procedures.

Of these three, the one that is least constrained by politics and culture is postabortion care, so it should be the area with the most potential for progress. Yet, postabortion care services remain incomplete, inferior or altogether unreachable for too many women in developing countries.

Elements of Postabortion Care

According to the most recent estimates, 8.5 million women annually faced injuries from unsafe abortions that required medical care, while only three million received treatment.3 Almost all unsafe abortions—98%—take place in developing nations, because the majority of such countries severely restrict legal abortion, which results in women’s reliance on clandestine procedures.1

Postabortion care encompasses a set of interventions to respond to the needs of women who have miscarried or induced an abortion. Over time, the view among medical and public health experts has evolved to define postabortion care services to include a comprehensive package of public health interventions beyond those oriented primarily around emergency medical treatment. Indeed, in 2002, the Postabortion Care (PAC) Consortium updated its model of postabortion care to include five essential, interrelated elements: treatment, family planning services, counseling, other reproductive and related health services, and community and service provider partnerships.4 The consortium represents international nongovernmental organizations with expertise in reproductive health and is the leading international forum for information and advocacy on postabortion care.

Both incomplete and unsafe abortions can lead to potentially life-threatening complications, so postabortion care services traditionally have centered around providing medical treatment. This entails use of high-quality methods such as manual vacuum aspiration (MVA) techniques or drugs such as misoprostol to complete incomplete abortions and halt bleeding. WHO strongly recommends the use of MVA over other surgical methods such as dilation and curettage (D&C),2,5 because MVA is safer, more cost-effective, less painful, less resource-intensive (no need for operating rooms or regular electricity) and can be performed by midlevel health providers at the primary care level (instead of physicians at tertiary facilities such as hospitals). As a result of broader MVA use, the accessibility, sustainability and quality of postabortion care services has increased. More recently, WHO has come to strongly recommend the use of misoprostol as a nonsurgical alternative.

Another key element of postabortion care is timely access to family planning services, including a broad choice of contraceptive methods to help space births, prevent future unintended pregnancies and avert unsafe abortions. Ideally, women would receive such family planning services at the time of postabortion care, rather than through referral. Counseling—a related but separate element—not only includes postabortion family planning education, but identification of the broader range of other physical and emotional health needs and concerns of the patient, to be addressed directly by the same provider or through referral to an accessible facility. Another affiliated component calls for linkages with additional reproductive and related health services available on site or through referral, including STI prevention, diagnosis and treatment; gender-based violence screenings; nutrition education; infertility counseling; hygiene education; and cancer screenings. Such linkages are important to ensuring that women’s broader sexual, reproductive and other health needs also are met.

Finally, this postabortion care construct recognizes that strong partnerships among community members and health care providers are critical to preventing unwanted pregnancies and unsafe abortion, to mobilizing resources so that women can obtain appropriate and timely care, and to ensuring that health services are responsive to community needs. Without community outreach and participation, efforts to prevent and treat unsafe abortion and to advocate for positive change will remain limited.

Current Challenges to Care

A multitude of practical and interrelated problems interfere with the availability of model postabortion care, including those involving cost, quality, access, supplies, provider training, stigma, and lack of treatment protocols and policy guidelines, to name a few. Several recent country-level analyses conducted by the Guttmacher Institute highlight some specific challenges and their impact on women, their families and communities.

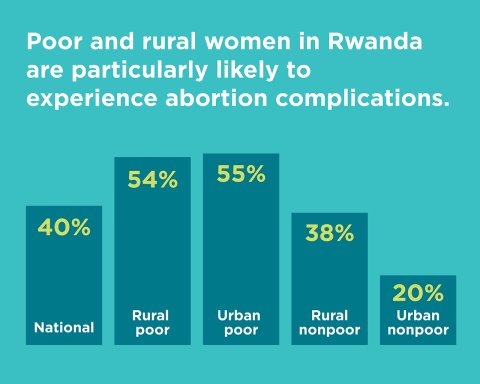

One common set of problems revolves around disparities in access to abortion-related services. In Rwanda, where abortion is legally restricted and access to safe abortion care is limited, poor and rural women are particularly likely to develop abortion complications (see chart).6 That likely stems in large part from a reliance on self-induced abortion, rather than abortions obtained from trained providers. Moreover, women who experience complications also face problems in access to postabortion care. Among all Rwandan women who suffered abortion complications and needed medical care, 30% did not receive it from a health facility, likely because not enough facilities were equipped to provide postabortion care and because many women wanted to avoid feeling stigmatized or mistreated as they often are when they do show up for care. The disparity between poor women and nonpoor women was stark, however: Some 38–43% of poor women did not obtain facility-based treatment, compared with 15–16% of nonpoor women.6 Poor women are also more likely to entirely forgo necessary medical care when facing abortion complications than their nonpoor counterparts. These women are especially likely to suffer debilitating consequences.

.png)

Although postabortion care literally can be life-saving, or at least critical to preventing serious illness or disability, obtaining that care often represents a significant economic burden, especially at the individual and family level. In Uganda, for example, Guttmacher found that the majority of women surveyed who had received treatment for unsafe abortion complications had experienced a decline in financial stability from the costs of their postabortion care: Some 73% had lost wages, 60% had had children deprived of food or school attendance or both, and 34% had faced a drop in the economic stability of their household.7 At the national level, the costs are also significant: An estimated $14 million is spent each year to treat the complications of unsafe abortion in Uganda.8

The costs of postabortion care can be mitigated in part by ensuring that health care facilities that provide treatment utilize the most current standard of care according to WHO—which is also less expensive than traditional treatment—and that such treatment protocols are delineated through national guidelines. In Colombia, for example, Guttmacher found that postabortion care services are significantly more costly at higher-level medical facilities (an average cost of $200 per patient) than at primary-level specialized facilities ($45), largely because of the former’s reliance on D&C, which is a more expensive and invasive procedure than alternatives, and is also less safe.9 The cost, coverage and quality of postabortion care could be vastly improved if misoprostol or MVA were more commonly used, and if nonspecialized providers were encouraged and trained to provide services.

Paths to Progress

Technical experts and advocates are advancing a number of recommendations to improve and scale up postabortion care, which range from education to address stigma and provider bias, to developing national medical protocols on postabortion care, to ensuring adequate and appropriate supplies and equipment. Meanwhile, two interventions in particular deserve increased attention, priority and resources because of their high-impact potential for protecting women’s health and saving lives: integrating family planning services into postabortion care and incorporating misoprostol into first-line treatment. The former should have been easier to accomplish than it has been, but instead has been a major challenge ever since postabortion care first appeared on the global health agenda more than two decades ago. The latter represents an important, relatively new treatment option with the potential to substantially expand the availability of services.

Family Planning

Because contraceptive use dramatically reduces the risk of future unintended pregnancies, repeat unsafe abortions, and maternal health complications and deaths, it plays a critical role in postabortion care. Even so, integration of family planning into postabortion care is uneven and difficult, for reasons ranging from shortfalls of contraceptive commodities to lack of provider knowledge and training at all tiers of the health system—especially the primary care level.

Unanimity about the importance of family planning in postabortion settings is apparent in expert policy statements and guidelines. The U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) has designated postabortion family planning as one of several proven high-impact practices in family planning. This label signifies its ability to maximize USAID family planning investments overall.10 In 2013, a group of key donors, medical associations and health organizations—the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO), International Confederation of Midwives, International Council of Nurses, USAID, White Ribbon Alliance, United Kingdom Department for International Development, and Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation—issued a joint consensus statement on their commitment to ensuring that "voluntary family planning counseling and services are included as an essential component of post abortion care in all settings."11

These and other experts have identified several best practices and recommendations to better incorporate family planning into postabortion care. First and foremost, family planning counseling, services and supplies should be provided at the same time and place as postabortion treatment. Women in these situations are more likely than those who are referred for services elsewhere to choose and use a method of contraception.10 Having a wide range of contraceptive methods available, including long-acting methods, is very important to protecting the ability of women to make informed choices and helping them select the method that best meets their needs and life circumstances. Almost all methods can be used immediately after postabortion care. Methods that are unavailable at primary-level facilities should be available elsewhere by direct referral. Similarly, referrals or other procedures should be in place to ensure that women can obtain ongoing contraceptive supplies if they choose methods that require additional or routine follow-up.

Expert recommendations also suggest shifting tasks to midlevel providers, who play an important part in expanding delivery of postabortion care. Training of providers in skilled postabortion counseling—including about family planning and STIs—goes hand-in-hand with recommendations for shifting tasks to lower-level or less specialized health providers, such as midwives, nurses and other staff. A broad range of providers can help ensure that postabortion family planning services are offered at all tiers of the health system, including through community-based counseling and outreach. Also important is the development of national guidelines on postabortion care that clearly address integrated family planning services.

Often hard to address but still essential to overcome are the social and cultural impediments to postabortion care. For example, a regularly overlooked recommendation is engaging men in postabortion family planning counseling. Many women would prefer that their partners be part of the decision-making process, but providers concentrate their counseling and services on women.10

Misoprostol

Although efforts to improve postabortion treatment in the 1990s focused mostly on expanding MVA use, the last decade has seen a push by public health experts and advocates for misoprostol. As a highly effective medical method of treating incomplete abortions, misoprostol may be used where surgical methods such as MVA are unavailable or to complement existing MVA services.

Originally marketed to treat gastric ulcers, misoprostol now has multiple uses, primarily in the area of obstetrics and gynecology. Because the drug contracts the uterus, it can reduce bleeding and, therefore, has proven highly valuable in preventing and treating postpartum hemorrhage—the top cause of pregnancy-related death in developing countries.12 It is also utilized to induce labor, as well as to perform a medication abortion; as an abortifacient, misoprostol is often combined with mifepristone, otherwise known as RU-486. Misoprostol’s ability to evacuate the uterus makes it also effective for treatment of incomplete abortions.

Misoprostol’s favorability among providers derives from its many advantages for a low-resource setting. Research shows it to be a safe and effective postabortion treatment method. It is inexpensive, does not need refrigeration and can be taken orally by tablet. Because of its simplicity, it may be administered practically anywhere by midlevel providers with no surgical training. As such, misoprostol has the potential to lower health costs and, more importantly, make postabortion care more available to women in their communities.

Medical bodies such as the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, FIGO and WHO have recommended misoprostol in postabortion care as an important intervention to reduce maternal mortality. In 2009, WHO added misoprostol to its model list of essential medicines—which provides guidance to nations on what medicines to stock—because of the drug’s track record of safety and effectiveness in treating complications of unsafe abortion.5 Two years later, WHO endorsed misoprostol again by placing it on the organization’s list of highest priority medicines to save mother’s and children’s lives.13

Despite the clear benefits of promoting misoprostol in postabortion care, the medicine has faced numerous political, bureaucratic and social barriers to gaining widespread acceptance. Among the toughest hurdles for misoprostol proponents is getting regulatory approval of the product in individual countries, which is an important precursor to making it more available in both the public and private market. Even though it is now available through the black market or used off-label in many developing countries, regulatory status—specifically for treatment of incomplete abortion—is still necessary to legitimize the drug among providers and consumers. In addition, to support an environment of safety standards and quality, misoprostol needs to be incorporated into medical protocols by governments and health professionals in-country.

Such standardization would go a long way in tackling the related challenges of provider preferences, differences and attitudes in treatment. Many providers are still relying on disfavored surgical methods or are otherwise reluctant to use misoprostol—for some, because of its alternative identity as an abortifacient. Punitive and restrictive abortion laws create disincentives and can stigmatize both providers and patients using misoprostol—even though postabortion care itself is generally legal.

Indeed, providers’ persistent bias against abortion and the women who rely on it has impeded the provision of dignified and respectful health care. Experts note the need for further education to sensitize both providers and community members that all women deserve health care without stigma or biased treatment, no matter who they are (young or old, married or unmarried) or what type of service they are seeking (abortion-related or not).

Running into Politics

Clearly, one of the biggest challenges to scaling up the use of misoprostol as a treatment option—and to delivery of postabortion care overall—is the association with abortion. Indeed, the skills, supplies and training that providers need to provide postabortion care are essentially the same as those needed to provide safe abortion care itself. This has presented a special dilemma for the United States, as postabortion care is an important, legitimate and widely supported (even by antiabortion activists) aspect of the U.S. reproductive health program overseas, while U.S. law prohibits support for abortion services in most circumstances.

The 1973 Helms amendment to the Foreign Assistance Act prohibits U.S. funds from paying for abortion when used "as a method of family planning." Importantly, this prohibition has never been interpreted—by antiabortion and prochoice administrations alike—to preclude USAID from including postabortion care programs within its global health portfolio. For example, the issue was raised in the context of the global gag rule, which disqualified foreign nongovernmental organizations from eligibility for U.S. family planning aid if they used non-U.S. funds to provide or advocate for access to safe abortion care. During 2001–2009, the last time the global gag rule was in effect, the antiabortion administration of George W. Bush made it clear that "treatment of injuries or illnesses caused by legal or illegal abortions, for example, post-abortion care" were explicitly permissible.14 When President Barack Obama took office in January 2009, he rescinded the global gag rule. Almost every year since then, antiabortion leaders in Congress have tried to legislate the gag rule back into effect (to no avail), but have continued to support postabortion care.

At the international level, 179 countries agreed to address the impact of unsafe abortion at the 1994 United Nations (UN) International Conference on Population and Development (ICPD), a seminal meeting that shifted the global development discourse toward meeting the reproductive health, rights and needs of women. The ICPD signatories recognized that "In all cases, women should have access to quality services for the management of complications arising from abortion. Post-abortion counseling, education and family-planning services should be offered promptly, which will also help to avoid repeat abortions."15 Subsequent UN conferences on women’s rights, such as the 1995 Beijing Conference and the ICPD+5 Conference in New York, reaffirmed this international consensus on postabortion care. Most recently, in a report reviewing progress on ICPD implementation, the UN Secretary-General urged governments to take concrete measures to minimize abortion-related complications and fatalities by providing nondiscriminatory postabortion care that meets WHO guidelines.16

For its part, USAID has been supporting postabortion care programs since 1994 in over 40 countries. The USAID approach condenses the PAC Consortium model into three elements: emergency treatment; family planning counseling and services, STI evaluation and treatment, and HIV counseling and referrals; and community empowerment. Its major objective is to increase availability of postabortion care "with particular emphasis on [family planning] counseling and services."17 This particular focus capitalizes on USAID’s strength in the reproductive health field, where historically it has been the world’s single largest donor for contraceptive services with a long history of deep expertise. It also provides a plausible way for the United States to avoid any appearance of getting too close to the line between postabortion care and safe abortion care.

Even though the United State is one of the world’s leading supporters of postabortion care activities, the depth and breadth of the U.S. involvement is limited as it tries to walk that line between actively promoting postabortion care while carefully avoiding support for abortion itself. One manifestation of that line is the decision by USAID to not buy critical supplies such as MVA kits and misoprostol tablets because they can be dually used to perform postabortion care and safe abortion care services. As a result, USAID’s commitment to postabortion care—as important and strong as it is—can only go so far.

For some time to come, politics undoubtedly will continue to dictate to USAID and other key players that ensuring access to comprehensive, quality postabortion care must operate on an entirely separate track from providing or facilitating access to safe abortion services. The global debate will rage on about the importance of recognizing access to safe abortion as the critical and necessary public health intervention that it is—one that enables women to avoid seeking risky, clandestine care. In the meantime, broad-based support already exists for helping women who suffer from the consequences of unsafe abortion. Policymakers, providers of care and donors can do much more to expand investment in comprehensive postabortion care. This includes making treatment safer, easier and more accessible with greater reliance on misoprostol, and ramping up postabortion contraceptive care to help women avoid another unintended pregnancy.

REFERENCES

1. Guttmacher Institute, Facts on induced abortion worldwide, In Brief, 2012, <http://www.guttmacher.org/pubs/fb_IAW.pdf>, accessed Feb. 16, 2014.

2. World Health Organization (WHO), Safe Abortion: Technical and Policy Guidance for Health Systems, second ed., Geneva: WHO, 2012, <http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/70914/1/9789241548434_eng.pdf>, accessed Feb. 16, 2014.

3. Singh S, Hospital admissions resulting from unsafe abortion: estimates from 13 developing countries, Lancet, 2006, 368(9550):1887–1892.

4. Postabortion Care (PAC) Consortium, PAC model, no date, <http://pac-consortium.org/index.php/pac-model>, accessed Feb. 16, 2014.

5. World Health Organization (WHO), Unedited draft report of the 17th expert committee on the selection and use of essential medicines, Geneva: WHO, 2009, <http://www.who.int/selection_medicines/committees/expert/17/WEBuneditedTRS_2009.pdf>, accessed Feb. 16, 2014.

6. Basinga P et al., Unintended Pregnancy and Induced Abortion in Rwanda: Causes and Consequences, New York: Guttmacher Institute, 2012, <http://www.guttmacher.org/pubs/unintended-pregnancy-Rwanda.pdf>, accessed Feb. 16, 2014.

7. Sundaram A et al., Documenting the individual and household-level cost of unsafe abortion in Uganda, International Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 2013, 39(4):174–184, <http://www.guttmacher.org/pubs/journals/3917413.pdf>, accessed Feb. 16, 2014.

8. Vlassoff M et al., The health system cost of post-abortion care in Uganda, Health Policy and Planning, 2014, 29(1):56–66, <http://heapol.oxfordjournals.org/content/29/1/56.full.html>.

9. Prada E, Maddow-Zimet I and Juarez F, The cost of postabortion care and legal abortion in Colombia, International Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 2013, 39(3):114–123, <http://www.guttmacher.org/pubs/journals/3911413.pdf>, accessed Feb. 16, 2014.

10. High Impact Practices in Family Planning (HIP), Postabortion Family Planning: Strengthening the Family Planning Component of Postabortion Care, Washington, DC: U.S. Agency for International Development, 2012, <http://www.fphighimpactpractices.org/sites/fphips/files/hip_pac_brief.pdf>, accessed Feb. 16, 2014.

11. Postabortion Care (PAC) Consortium, Post abortion family planning: a key component of post abortion care, 2013, <http://www.pac-consortium.org/attachments/article/69/PAC-FP-Joint-Statement-November2013.pdf>, accessed Feb. 16, 2014.

12. World Health Organization (WHO), WHO Recommendations for the Prevention and Treatment of Postpartum Haemorrhage, Geneva: WHO, 2012, <http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/ 10665/75411/1/9789241548502_eng.pdf>, accessed Mar. 4, 2014.

13. World Health Organization (WHO), Priority life-saving medicines for women and children, 2012, <http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/75154/1/WHO_EMP_MAR_2012.1_eng.pdf>, accessed Feb. 21, 2014.

14. Executive Office of the President, Restoration of the Mexico City policy, Federal Register, 2001, 66(61):17303–17313, <http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2001-03-29/pdf/01-8011.pdf>, accessed Aug. 27, 2013.

15. United Nations Population Information Network (POPIN), Report of the ICPD, 1994, <http://www.un.org/popin/icpd/conference/offeng/poa.html>, accessed Feb. 21, 2014.

16. United Nations Economic and Social Council, Commission on Population and Development, Framework of actions for the follow-up to the Programme of Action of the International Conference on Population and Development (ICPD) beyond 2014, 2013, <http://icpdbeyond2014.org/uploads/browser/files/sg_report_on_icpd_ operational_review_final.unedited.pdf>, accessed Mar. 4, 2014.

17. U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), Postabortion Care Global Resources: A Guide for Program Design, Implementation, and Evaluation, Washington, DC: USAID, 2007, <http://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PNADU081.pdf>, accessed Feb. 16, 2014.