In 1994, official delegations from more than 180 countries gathered in Cairo at the United Nation’s International Conference on Population and Development (ICPD) and agreed to a dramatically different approach to population issues.The Program of Action that emerged from the conference was groundbreaking. Under the rubric of improving global sexual and reproductive health, it called for moving beyond country-level macrodemographic targets for population size to a primary focus on meeting the rights, needs and aspirations of individual women and men.The Program of Action was striking in its insistence that enabling people to decide freely the number, spacing and timing of their children is fundamental to the strategic and economic interests of all countries.Toward that goal, it also called for a significant expansion of services to acknowledge and address the sexual and reproductive health needs of adolescents.

This year marks the 15th anniversary of ICPD, and in September, civil society leaders from around the world convened in Berlin to take stock of the progress—and what remains to be done. Although young people themselves for the most part did not participate in Cairo, they played a prominent role in Berlin. Youth aged 15–29 made up more than 25% of those in attendance at the Global Partners in Action Nongovernmental Organization (NGO) Forum on Sexual and Reproductive Health and Development. Moreover, the Youth Coalition—an international organization of young people that was created at the five-year review of ICPD and is committed to promoting sexual and reproductive rights—organized a special youth symposium, which resulted in a statement that boldly calls on policymakers and other stakeholders around the globe to push for a more inclusive and progressive sexual and reproductive health agenda.

One would think that for American sexual and reproductive health advocates, the NGO Forum could not have come at a better time. President Obama is strongly committed to women's health and international family planning assistance, as evidenced by the rescission of the Bush-era "global gag rule" and his restoration of the United States' support for the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA). The president has publicly stated his support for age-appropriate, comprehensive sex education for youth, and his blueprint budget for FY 2010 called for an end to abstinence-only programs in the United States.

Despite these encouraging signals, however, the Obama administration has not yet made any notable changes to U.S. policy targeting the sexual and reproductive health of young people globally. Under the Bush administration, the United States promoted premarital abstinence as the single most important strategy for youth worldwide. Youth activists argue that Obama needs to quicken his pace on the administration's promise to take a different approach. In preparation for that day, the key questions are what progress has been made in meeting the sexual and reproductive health of young people since 1994? What more needs to be done to achieve adolescent sexual and reproductive health? And how well-equipped is U.S. policy to get the job done?

Taking Stock

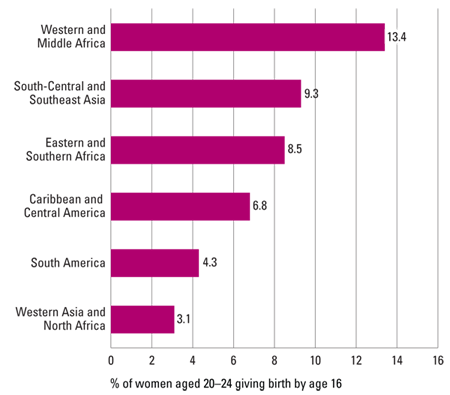

Two reports published earlier this year—Young People and Universal Access to Reproductive Health, published by the Youth Coalition, and Healthy Expectations: Celebrating Achievements of the Cairo Consensus and Highlighting the Urgency for Action, published by UNFPA—take a look back at what has been achieved in the first 15 years of the 20-year Cairo Program of Action and highlight what is needed to fully achieve the Cairo goals, as well as other global commitments. These reports draw attention to the fact that today's youth represent the largest generation in history. To prepare for the future, they will need education, training and job opportunities; they also must be free of widespread disease, unplanned pregnancy, violence and discrimination. The good news is that contraceptive use by married and unmarried adolescents is more common than in the past, and as a result, rates of adolescent childbearing have dropped significantly in most countries and regions over the last few decades. Nonetheless, more than 16 million adolescents give birth each year, and in some regions of the world, early childbearing is common. As many as one in 10 women in Africa and South Asia have their first child before the age of 16 (see chart). Having a baby always carries potential risks, but for young adolescents, the risks are even greater. Women under the age of 16 are more likely than those who are older to experience premature labor, miscarriage and stillbirth, as well as death from pregnancy-related causes.

| TOO-YOUNG PARENTS |

|---|

| Many young women in the developing world have their first child before age 16, when pregnancy and childbirth is particularly dangerous for mother and child. |

|

| Source: Institute of Medicine, 2005. |

Most births to teen mothers occur within marriage and are planned, but millions are not, and in many such cases, a young woman may seek to terminate her pregnancy. Adolescents aged 15–19 are estimated to have 2.5 million of the approximately 19 million unsafe abortions that occur annually in the developing world. Unsafe clandestine abortions endanger the health—or the very life—of young women, and adolescents frequently make up a large proportion of patients who are hospitalized for complications from such procedures. Even in places where abortion is legally available, a young woman may face obstacles: For example, she may not quickly recognize she is pregnant, may not have the money readily available to pay for an abortion or may be required to get a parent's or her husband's consent before having an abortion.

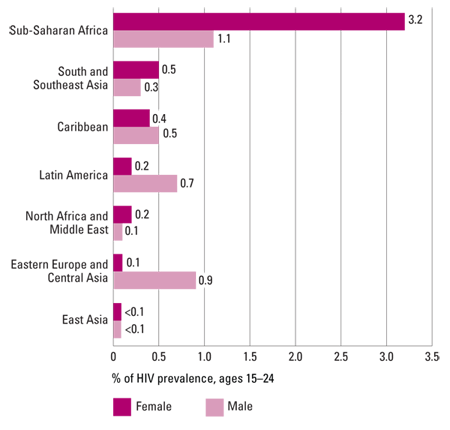

Although mortality and morbidity related to pregnancy, delivery and unsafe abortion remain the most significant risks to young women's health, in some parts of the world, young women also face a substantial risk of AIDS. Worldwide, young people aged 15–24 account for nearly half of all new cases of HIV infection, and young women are more greatly affected than young men. In Sub-Saharan Africa—the region of the world where the majority of people with HIV live—young women are three times more likely than young men to be infected (see chart, page 9).

Despite widespread awareness of pregnancy and AIDS, adolescents' knowledge of these subjects is not comprehensive, and myths are common. According to a multiyear, multicountry study of adolescents in Sub-Saharan Africa conducted by the Guttmacher Institute, many adolescents think that a young woman cannot get pregnant the first time she has sexual intercourse or if she has sex standing up, that they can identify someone living with HIV by their outward physical appearance, that HIV can be transmitted through a mosquito bite or that a man who is HIV-positive can be cured by having sex with a virgin.

Importantly, adolescents recognize their need for better information and want it to come from reliable sources they trust. In Uganda—one of the study's focus countries—about half of all young people said, unprompted, that they would like to get information about contraceptive methods, HIV and other STIs from teachers, health care providers or the mass media, whereas just one-third would prefer to receive information from family and one-fifth from friends. When asked why they preferred the more formal sources, young people said those sources could be trusted to provide reliable information.

A Bold Agenda

One day prior to the official start of the NGO Forum in Berlin, more than 70 young delegates from 66 countries gathered for a youth symposium to develop key messages to promote during the forum. The resulting youth symposium statement strongly challenges policymakers and other decision makers to strengthen their commitment to the Cairo Program of Action "regardless of the political environment [or] donors' and country donors' agendas" and to move beyond Cairo by recognizing young people's rights. The statement outlines a number of key action areas, including the promotion of comprehensive sex education, the provision of sustainable sexual and reproductive health services, and the involvement of young people in decisions about programs and policies that affect them.

| A MORTAL THREAT |

|---|

| Particularly in Sub-Saharan Africa, HIV is a prevalent and worrisome danger for youth. |

|

| Source: UNAIDS, 2008. |

Sex education. The youth symposium statement sets a goal of "accurate, timely and evidence-based" comprehensive sex education and calls on policymakers to promote programs both in and out of school. The statement emphasizes that young people not only have the right to be safe and free from coercion, discrimination and violence in intimate partner relationships, but that they also have the right to "enjoy their sexuality in a…pleasurable way." Toward this goal, all sectors of society that are involved in sex education—from teachers to community health workers to donors to ministries of health—need to be "fully informed [and] sensitized on youth issues and empowered to act in the best interests of young people."

Sexual and reproductive health services for youth. The statement recognizes that for young people to achieve their sexual and reproductive rights, they need access to a wide array of services. To be effective, services must be provided by caregivers who have been trained to work with young people, in an environment in which adolescents feel comfortable. The statement calls for the elimination of the legal barriers, such as parental and spousal consent laws and restrictive abortion policies, that stand in the way of young people's accessing the health care they need. It also acknowledges that privacy and confidentiality are important aspects of service provision for adolescents, who may be uncomfortable discussing sexual matters or may fear condemnation from their families or communities if they reveal their sexual activity.

Meaningful youth involvement. The youth symposium statement calls on policymakers, public health experts and national-level program planners to involve young people themselves when considering the sexual and reproductive health needs of youth. Youth-led organizations have a key role to play at all stages in the process—from program and policy design to the delivery and evaluation of sexual and reproductive health services. Governments, donors and NGOs must invest in mentoring programs and in the capacity of youth groups to participate fully in program design and implementation.

The statement also celebrates the diversity of young people around the world and does not shy away from recognizing young people on the margins of society. "We are young people; women, men, lesbians, gays, heterosexuals, transgender; in school, out of school, sex workers, married, divorced, single or in a relationship; we live with HIV and AIDS; we are disabled; we are migrants, refugees, displaced, trafficked; we are working, jobless or seeking employment; we speak different languages; we have different spiritual beliefs and practices; we have different perceptions of the world around us; we use different media and social networks to communicate globally." The statement demands that policymakers and program managers "acknowledge and respect our diversity…and eliminate the existing policies that discriminate against us."

Beyond Cairo. Finally, the youth symposium statement calls on policymakers to "think beyond Cairo," by pushing for a "more inclusive and progressive agenda"—one that recognizes sexual rights and works toward the elimination of gender bias and other social, economic and legal barriers that prevent adolescents from accessing sexual and reproductive health services and "fully enjoying their sexuality." The statement's support for young people's rights is unflinching, even in the face of cultural differences: "We recognize the value of cultural differences and do not perceive it as a barrier for fully realizing young people's sexual and reproductive health and rights, and cultural practices should not compromise young people's rights."

The U.S. Response

The United States has been and remains the single largest contributor of funds for programs around the world designed to prevent teenage pregnancy and HIV, and U.S. policy is critical in shaping health and development programs for youth worldwide. Two U.S. government agencies in particular have assumed a significant role in sexual and reproductive health programs for youth globally: the Office of the U.S. Global AIDS Coordinator, which oversees the implementation of the President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), and the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID).

PEPFAR, originally enacted in 2003, is widely credited for providing life-saving medicines to more than two million people living with HIV. Last summer, the United States strongly recommitted itself to fighting AIDS, by agreeing to renew PEPFAR for another five years. The new PEPFAR statute is improved in many ways. For example, it bolsters its previous treatment focus with an increased emphasis on care and support services for people living with HIV, allows for a slight increase in the proportion of funding that may go toward prevention and accounts for some of the broader public health implications of HIV. Yet, PEPFAR's fundamental prevention policy remains fraught with proscriptions and prescriptions that continue to hamper the program's ability to support the most effective interventions at the local level.

Regarding youth, the original PEPFAR mandated a rigid spending requirement that one-third of all HIV prevention funds be reserved for abstinence-only programs, whereas the new statute includes a more flexible goal. It stipulates that in those countries with generalized epidemics, the global AIDS coordinator must develop an HIV sexual prevention strategy for which at least half of funding supports "activities promoting abstinence, delay of sexual debut, monogamy, fidelity and partner reduction." The coordinator must report back to Congress on any country strategy that does not meet this goal and provide a justification for this decision.

In short, PEPFAR still promotes abstinence and fidelity, but in a more circumscribed way that leaves room for interpretation. It is now up to the Obama administration to determine which programs and interventions to fund to most effectively achieve these outcomes. So far, however, the administration has not issued new guidance to the field to address youth issues; as a result, global AIDS programs for youth continue to be driven by guidance originally issued by the Bush administration in 2005. According to the ABC Guidance ("ABC" is short for abstain, be faithful and use condoms), PEFPAR's primary message for youth and other unmarried persons is abstinence until marriage. In recognition of the fact that many young people engage in sex before marriage, PEPFAR's answer is "secondary abstinence." PEPFAR funds may not be used to distribute condoms in schools or for youth-targeting social marketing campaigns that encourage condom use, because these interventions "give a conflicting message" and "appear to encourage sexual activity or appear to present abstinence and condom use as equally viable, alternative choices." Eric Goosby, the new global AIDS coordinator, acknowledges that the guidance needs to be revisited, but has moved tentatively and has not provided a specific plan for doing so.

Meanwhile, USAID's office of population and reproductive health has traditionally focused on reproductive health interventions for youth. Between 1994 and 2006, the office supported two major projects. The first of these, FOCUS on Young Adults, built awareness and supported research to identify appropriate strategies for promoting youth reproductive health and preventing HIV. The second, YouthNet, shifted the emphasis to program expansion, adaptation, institutionalization and sustainability of successful strategies. When YouthNet came to an end in 2006—well into the Bush administration's second term—the agency decided to no longer support sexual and reproductive health projects focused solely on youth and, instead, to incorporate youth interventions into larger projects. Staff within USAID acknowledge that, although there may have been sound reasons for "mainstreaming" youth activities into other projects, the U.S. government has lost ground since 2006. In some cases, youth activities continued with limited resources or became lower profile to avoid political controversy; in other cases, interventions withered away altogether.

Since Obama's election, there has been renewed interest within USAID to reinvigorate reproductive health programs for youth. The agency is considering partnering with other organizations to provide technical assistance and strengthen existing youth education and service programs in poor countries. USAID's interagency youth working group, meanwhile, continues to serve as a network where NGOs, donors and cooperating agencies can share research and programmatic results. And yet, USAID has been hampered in its efforts to reclaim global leadership in youth reproductive health by its own lack of leadership. After a 10-month search for a USAID director, President Obama in early November nominated Rajiv Shah, a doctor and agriculture expert, to the post. Shah's nomination, which must be approved by the Senate, comes as the White House and the State Department are studying how to redesign U.S. foreign aid assistance for global health. "Shah has a difficult job ahead of him, and there are many competing priorities," says Gwyn Hainsworth, senior adolescent sexual and reproductive health advisor at Pathfinder International. "In many countries, sexual activity among young people prior to marriage remains stigmatized, and policymakers may be reluctant to expand the capacity of teachers and health care providers to effectively provide sexual health information and services to young people. Additionally, the fact that many young people in developing countries are already married and have reproductive health needs is often overlooked. It will take strong leadership to break through these political obstacles."

Young people themselves recognize these political obstacles, but say the time for change is now. "We have strong allies in the administration," says Katie Chau, a member of the Youth Coalition. "Now is an important time to focus our advocacy efforts and make sure that policies that affect youth are evidence-based. Many of our members live in countries that receive U.S. funding for global AIDS or family planning, and they feel the impact of U.S. policies on their own health. Strengthening sexual and reproductive health and rights is a pressing global need. It's time we quicken the pace and move to a more progressive agenda."