Updated on December 1, 2022:

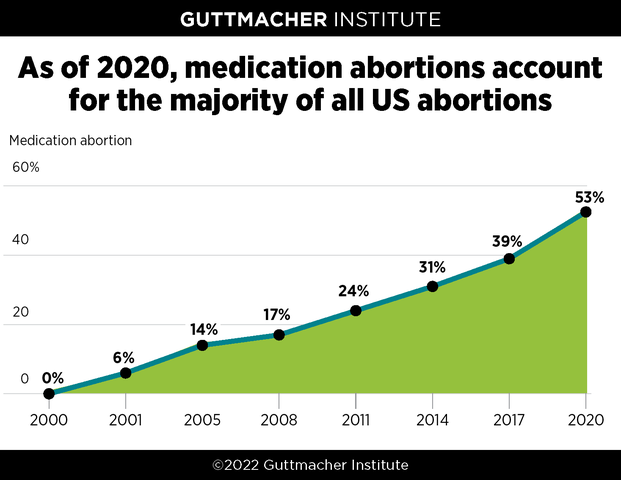

This analysis and accompanying graphic have been updated to reflect the final data from Guttmacher’s census of all known abortion providers, which found that medication abortion accounted for 53% of all facility-based abortions in the United States in 2020. Preliminary data, originally published on February 24, 2022, indicated that medication abortion accounted for 54% of all abortions.

The full 2020 Abortion Provider Census can be found here.

First published on February 24, 2022:

In 2000, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved mifepristone as a method of abortion. Taken along with misoprostol, the two-drug combination is known as medication abortion or the "abortion pill." New research from the Guttmacher Institute shows that 20 years after its introduction, medication abortion accounted for more than half of all abortions in the United States.

Guttmacher Institute’s periodic census of all known abortion providers show that in 2020, medication abortion accounted for 53% of US abortions. That year is the first time medication abortion crossed the threshold to become the majority of all abortions and it is a significant jump from 39% in 2017, when Guttmacher last reported these data. Preliminary data originally published in February 2022 showed that medication abortion accounted for 54% of all abortions in the US.

This new data point powerfully illustrates that medication abortion has gained broad acceptance from both abortion patients and providers. It also underscores how central this method has become to US abortion provision, thanks to its track record of safe and effective use for more than two decades. As medication abortion has become the most common method of abortion, there is still the potential to further increase access—which is why the method has become a main target of anti-abortion politicians and activists seeking to restrict care.

Medication Abortion Is a Safe and Effective Option

Currently, medication abortion is approved for use up to 10 weeks of pregnancy. The FDA approved that limit based on research the agency reviewed at the time. However, additional research shows provision beyond 10 weeks is safe and effective and some providers administer medication abortion "off label" after that point in pregnancy.

Patients initiate a medication abortion by taking mifepristone, followed by misoprostol one or two days later, as directed by a provider or the manufacturer’s instructions. Medication abortion differs from procedural abortion, which is provided in a clinical setting via vacuum aspiration or another method. Patients should always have the full scope of options available to them, including in-person care with a clinician.

Medication abortion can be completed outside of a medical setting—for example, in the comfort and privacy of one’s home. Pills can be provided at a clinic or delivered directly to a patient through the mail. The latter option can be especially useful in addressing logistical burdens abortion patients often face when they have to visit a provider to obtain care, such as arranging for child care and time off work and paying for transportation costs. And, in areas of the country that are rural or underserved by providers, medication abortion can save a patient hundreds of miles of travel.

Throughout the more than 20 years that it has been used in the United States, medication abortion has been proven to be overwhelmingly safe and effective.

A comprehensive review of the science related to the provision of abortion care in the United States conducted by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine confirmed that medication abortion has a very low rate of serious complications and is effective at ending an early pregnancy.

Subsequent research has demonstrated that direct-to-patient medication abortion provided via telemedicine—where the patient remotely consults with a provider and pills are shipped through the mail—is likewise safe and effective and works well for patients.

Transforming the Landscape of Abortion in the United States

A number of factors have transformed the landscape around medication abortion in recent years. While the use of medication abortion has been steadily increasing since it was first approved, the COVID-19 pandemic likely accelerated that trend. Since the start of the pandemic in early 2020, there has been increased attention on the benefits of telehealth—and abortion has very much been a part of that conversation.

Another factor improving access has been an increase in evidence-based policies that allow non-physician medical professionals—such as physician assistants and advanced practice nurses—to provide medication abortion. Broadening the pool of qualified providers is in line with expert guidance. There has also been an increase in clinics that only provide medication abortion and not procedural care.

Despite its long-standing safety record, mifepristone has been subject to a medically unwarranted Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) imposed by the FDA with the drug’s approval in 2000. Under the requirements of this restriction, the medication had to be dispensed only by certified prescribers, patients had to sign an agreement stating they were told about potential side effects of the medication and pills had to be dispensed in clinics, medical offices or hospitals (not pharmacies).

In April 2021, the FDA announced it would allow abortion pills to be mailed to patients for the duration of the pandemic. This action meant patients could obtain an abortion without making one (or several) in-person visits to a health care facility and risking unnecessary exposure to COVID-19. The change also allowed online-only abortion providers to mail pills to patients in more states.

After years of petitions to reevaluate the REMS based on mifepristone’s decades-long safety record, the FDA issued a permanent decision in December 2021 to allow mailing of the pills and also expanded access through pharmacies. However, guidelines on pharmacy access have not yet been developed.

State Policies Determine Level of Access

Because medication abortion is a great option for patients and can be taken safely and effectively outside of a clinic setting, it has long been a target of abortion opponents. The lifting of mailing restrictions has predictably encouraged abortion opponents to quickly enact additional burdensome and medically unnecessary restrictions on medication abortion. These attacks have been paired with renewed efforts to misrepresent the method’s safety record and otherwise attempt to stigmatize it and deter its use.

As part of that larger strategy, anti-abortion policymakers have long pursued state-level restrictions to limit access to medication abortion, a push that may further intensify this year. As of February 2022:

In 32 states, clinicians who administer medication abortion are required to be physicians, even though medical professionals with different titles and specialties are otherwise allowed to prescribe medications, oversee treatments and manage patients’ health.

- This is an effort to limit the availability of medication abortion, which particularly affects patients in rural or underserved areas where there may not be consistent access to a physician.

Texas prohibits the use of medication abortion starting at seven weeks of pregnancy, which is a politically determined limit at odds with current medical guidance. Indiana bans its use at 10 weeks, which corresponds to current FDA guidance, but prevents expanded access in the future.

In 19 states, the clinician providing a medication abortion must be physically present when the medication is administered, thereby prohibiting the use of telemedicine to prescribe medication for abortion.

In three states, mailing abortion pills to patients is currently banned (Arizona, Arkansas and Texas); mailing bans in another three states (Montana, Oklahoma and South Dakota) have been blocked by courts.

In January 2022, South Dakota approved regulations that would have required patients to make four trips to a clinic in order to obtain a medication abortion. Enforcement of these regulations has been blocked pending the outcome of litigation.

Already this year (as of February 22, 2022), 16 state legislatures have introduced bans or restrictions on medication abortion, including legislation that would ban the use of medication abortion in seven states (Alabama, Arizona, Illinois, Iowa, South Dakota, Washington and Wyoming), specifically prohibit the mailing of abortion pills in five states (Georgia, Kentucky, Maryland, Massachusetts and Nebraska) and bar the use of telehealth to provide medication abortion in eight states (Georgia, Iowa, Kentucky, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Nebraska, South Dakota and Tennessee).

Challenges and Opportunities Ahead

Given the reality of the 6-3 anti-abortion majority on the US Supreme Court that is now primed to severely weaken or overturn Roe v. Wade outright, medication abortion is likely to become even more critical in the delivery of care to many people who may be unable to access care in a clinic, as well as the target of additional ideological attacks.

A recent Guttmacher analysis predicts that if Roe v. Wade is overturned, there are 26 states certain or likely to quickly ban abortion to the fullest extent allowed by the Supreme Court. For medication abortion, additional restrictions could include more states passing a ban on mailing of medications or even attempts to block legal channels for patients to receive this care by leaving their home state.

Before abortion was legalized across the country in 1973, quality of care and health risks were widespread concerns for patients without legal access to the procedure. Given general medical advancements in the past 50 years and mifepristone’s safety record during more than 20 years of use, a larger worry among medical professionals and advocates today is the potential legal risk to patients, providers and anyone who assists someone in obtaining a medication abortion in states where it may be banned or criminalized. Actions that pose a risk for prosecution could include obtaining pills through alternative channels, such as online providers and clinics across state lines.

Such a scenario is likely to further exacerbate existing racist and discriminatory law enforcement practices that target and disproportionately criminalize Black, brown and other people of color for their pregnancy outcomes. Furthermore, people of color account for the majority of abortion patients in the United States and they will be the most severely affected by denial of abortion care.

Looking at this landscape, states with policies supportive of abortion rights must redouble their efforts to further codify, reinforce and expand those protective policies. Federal action is also needed to put a stop to the barrage of state-level restrictions and attempts at outright bans on the use of medication abortion. The Women’s Health Protection Act is federal legislation that would protect access to abortion—whether someone lives in California or Texas—by establishing a right under federal law to deliver and receive abortion care without medically unnecessary restrictions and bans, including restrictions on the use of telehealth for medication abortion.

The introduction and availability of medication abortion has proven to be a game changer in expanding abortion care in the United States, and it will likely be an even more important option for people to obtain an abortion as many states continue to pass legislation to bar or restrict abortion access.

Methodology

Every three years, the Guttmacher Institute contacts all known facilities providing abortion in the country to collect information about service provision, including the total number of medication abortions provided. The most recent survey, collecting information for 2019 and 2020, is available here. Preliminary data, published in February 2022, reflected information obtained from approximately 75% of US clinics that provided abortion care in 2020; the final proportion of all abortions represented by medication abortion changed by only one percentage point. These counts only include provision of medication abortion overseen by clinicians and do not account for self-managed abortion.

Hospitals accounted for only 3% of abortions provided in all survey years. Figures in the above graphic for 2000–2014 do not include abortions provided in hospitals, while those for 2017 and 2020 do. If figures were adjusted to account for that share, the proportion of all abortions that were medication abortions in 2000–2014 would be the same or one percentage point lower.